Bad Girls, Good Girls

April 18, 2013

Lately I’ve been sleeping with bad boys.

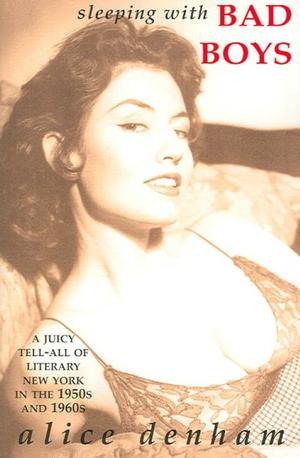

Whoops, I mean I’ve been reading Sleeping with Bad Boys (Book Republic, 2006), novelist and Playboy centerfold model Alice Denham’s memoir of the fifties and sixties literary scene in New York. She crossed paths with most of the major American writers during that period and, as the title implies, bedded many of them. And even though she dishes on dick size now and then, the book is more of a literary memoir than a boudoir tell-all. Denham’s frankness about her drive to succeed as a novelist, and to be recognized as an equal by her male peers, is an appealing story, and she sketches a detailed, fascinating portrait of the boozy, thuddingly sexist Manhattan of the immediate pre-Mad Men era.

If you’re wondering why I’m writing about this here, it’s because inevitably Denham also met (and, yes, slept with) a lot of people who were active in television in the fifties. The scenes overlapped; the literary crowd, including Denham, could make a quick buck in television (or on it, in Denham’s case, since she was cute enough to get hired for TV ads). Denham describes brief encounters with sometime TV scribes like Gore Vidal, Vance Bourjaily, and Barnaby Conrad. She had an intimate friendship with James Dean during his live TV days, and grew up (in Washington, D.C.) with Dean’s friend Christine White, an actress who played leads on The Twilight Zone and Alfred Hitchcock Presents but disappeared by the mid-sixties. (Denham writes that White became a “Jesus freak,” recruiting converts on street corners). Denham dated Ralph Meeker for a while, and Gary Crosby – one of Bing’s balding, no-talent actor sons – once offered her a hundred bucks for sex. (Did she accept? Read the book.)

One of Denham’s most interesting brushes with television came just before the quiz show scandals. She knew Steve Carlin, the producer of The $64,000 Challenge, and Carlin hired her for a “test” broadcast of the show. Because it wasn’t “real,” Carlin told her which question to lose on, even though she knew the answer, and Denham did as she was told. Only after the scandals broke did she realize that Carlin probably did that with everyone. That’s an especially duplicitous method for rigging the shows that I hadn’t heard of before.

Finally there’s Gardner McKay, another of Denham’s fifties boyfriends. I knew that McKay left Hollywood to become a painter, but I’d always imagined him dabbing away at godawful still lifes on a beach somewhere. In fact, Denham’s sketch of the six-foot-five dreamboat portrays him as a serious artist, struggling to express himself as she was, and venturing reluctantly into acting out of the same economic necessity that compelled her to shuck her clothes. Maybe that’s why I always found McKay so fascinating on Adventures in Paradise. Beneath his woodenness, there was an aloof quality, a hardcore indifference that made him just right to play a footloose, beachcombing adventurer, unfazed by any of the trouble he encountered on the seas and in sketchy ports. Those other stiffs, the Robert Conrads and the Troy Donahues, were trying too hard. McKay, as they always used to say of Robert Mitchum, really didn’t give a damn.

*

Anne Francis was a more prominent and more ambiguous sex symbol than Denham, a creature unique to the fifties-sixties celluloid realm in which screen goddesses were either lushly available (Kim Novak) or coyly off-limits (Doris Day). More than anyone else, Francis mashed up both into a confusing package: she had Marilyn Monroe’s beauty mark, adorning a bobbysoxer’s cute, dimpled smile. She was eminently feminine but, like the equally fascinating Beverly Garland, also a pants-wearing ass-kicker. Francis’s career-defining role was also one that broke down gender barriers, however tentatively, imagining her as an action star who kicked literal ass every week – even if you could always tell that a stuntman in a wig subbed in for Francis in the long shots. Honey West was a terrible show, a condescending and brain-dead dud that producer Aaron Spelling dumbed down from a sparkling Link & Levinson premise. And yet so many of us bend over backwards to pretend that Honey West doesn’t suck, and that’s entirely because of Francis. She played the blithe, lithe private eye so confidently, so deliciously, that in our heads it morphs from cartoonish junk that pitted poor Honey against Robin Hood and guys in gorilla suits into a sophisticated show about a heroine who vanquishes formidable bad guys (and sleeps with bad boys).

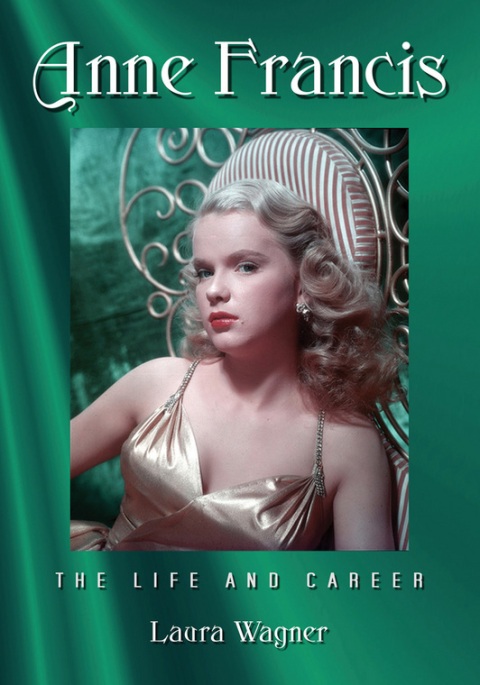

Francis was never quite an A-list star but she remains widely adored by movie and TV buffs, an object of desire for the men and of empowerment for women. That puts her in the category of performers who warrant book-length treatment, but only – and so often to their detriment – by semi-professional authors working for semi-professional trade presses like McFarland or Bear Manor Media. Francis’s turn came two years ago in a book by Laura Wagner.

Something of a minor cult figure herself, Laura Wagner has a loyal circle on Facebook, where she writes a de facto blog profiling Golden Age movie actors (many of them tantalizingly obscure). These “birthday salutes” are pithy, well-researched, and often enriched with revealing quotes from widows and children. But sometimes the real attraction seems to be the cathartic scorn that Wagner (who also writes for Classic Images and Films of the Golden Age) heaps upon readers who leave comments or ask questions without first reading her articles. (You’d think people would stop making that mistake after a while, but they don’t.)

So I was disappointed to find that Wagner’s Anne Francis: The Life and Career (McFarland, 2011) has little of the energy or the inquisitive rigor of her short-form work. It’s a dutiful, conservative, and surprisingly incurious account of Francis’s eighty years, one that gathers enough facts to intrigue readers but ultimately fails to suss out whatever inner life fueled Francis’s distinctive perky-sexy screen personality. Francis had two early, failed marriages, one to a troubled filmmaker-poseur named Bamlet Price, the other to a Beverly Hills dentist; and she had two children, one by the dentist and the other adopted when she was forty. She was a single mother of two daughters when it was still uncommon (her adoption was one of the first granted to an unmarried woman by a California court), and also a flaky enlightenment-seeker of a uniquely SoCal stripe; there were associations with obscure metaphysical churches, forays into motivational speaking, and even a barely-published autobiography called Voices From Home: An Inner Journey.

But we learn little about any of that, or any deeper or darker stories in Francis’s life, apart from what was reported in the personality columns. Wagner rounds up hundreds of generic Francis quotes from impersonal newspaper interviews, and some livelier and slightly more introspective lines from the chatty and now sadly defunct website that Francis maintained in the early 2000s (an archive of which would probably have more value than this book). Here and there, the batting about of quotes works. If you’ve ever wondered why Francis has such a nothing part in William Wyler’s Funny Girl, Wagner stitches together a plausible explanation, and untangles the minor controversy of what complaints Francis did or did not lodge publicly against her co-star Barbra Streisand. But much of the book is perversely dry. Glamour Girls of the Silver Screen gives a somewhat juicier peek at Francis’s romantic life, citing flings with Buddy Bregman, actor Liam Sullivan, and director Herman Hoffman, all of which remain uninvestigated by Wagner. And Tom Weaver, a more incisive historian who knew Francis well and who should have written this book, has published anecdotes that portray her as vital and down-to-earth:

My favorite day with her: Riding around Westchester County (NY) with her and my brother: Going to Ossining (where she was born), showing her Sing Sing (the Francis family physician was unavailable, so she was delivered by the Sing Sing doctor), finding her childhood home in Peekskill, going to some cemetery and finding the grave of her mother (or father? I forget), etc.

Then a whole bunch of us (two cars worth) got together at some steak house in Irvington for lunch. On the highway afterwards, I realized I’d brought along a couple VHS tapes to give to a buddy (a guy who’d been at the lunch), and forgotten. But my brother pointed ahead on the road and said, “Well, there’s his car.” Anne (riding shotgun) said, “Give me the tapes!” We got up to about 75 or 80 MPH to catch up with the other car, and she kinda got up and stuck her head and shoulders out the window and, at 75 or 80 MPH, she handed the tapes to the driver of the other car.

Why aren’t those stories in the book? Instead Wagner contents herself by weighing in on just about every Francis performance, which she does in two separate, consecutive slogs through the actress’s CV: a biographical narrative with a heavy emphasis on the work over the personal life, and then an arguably redundant annotated filmography (which comprises almost half of the book’s 257 pages). This tack does permit Wagner to highlight some overlooked performances and dig up some obscure odds and ends that any Francis cultist will covet. For instance, there’s Survival, the essentially unreleased experimental debut film (filmed in 1969, unfinished until 1976) by director Michael Campus (The Mack), which was written by the great John D. F. Black and seems to be unfindable today. There’s Gemini Rising, the only thing Francis directed, a short film set at a rodeo; Francis was a buff, and it’s unsurprising that she was at home in such a masculine environment. Then there was the unsold pilot for a syndicated proto-reality series in which Anne would have fixed up things around the house each week (“plumbing, carpentry, and electricity”!). Anne Francis, plunging a toilet: I would have watched that show.

Unfortunately, Wagner’s filmography double-tap also draws out a lot of self-indulgent stabs at criticism that are dubiously relevant and mostly devoid of insight. Here’s one of the strangest misreadings of The Fugitive that I’ve ever run across:

Week after week, Kimble would travel around, befriending strangers, all of whom were supposed to sense his innate goodness and innocence and allow him to move on to the next town to resume his search. The problem with this is quite apparent herein. Janssen played Kimble as brooding, mumbling, never making eye contact, always giving evasive answers. There was nothing attractive or honest about him.

And a review of an Alfred Hitchcock Hour that might have been written for a junior high school newspaper:

Anne gives a sympathetic showing here as a woman dissatisfied with her life and feeling trapped by her loveless marriage, turning to booze and boys to fill the void. (Nice work, if you can get it.)

The suspense is palpable in this episode, but it is almost ruined by Rhodes’ one-note performance and Strauss’ wildly fluctuating one. Physically the darkly gorgeous Rhodes, who was dating Anne at the time, is perfect for the part, and he is convincing in their love scenes, but someone should have coached him on his lines. Ah, the beautiful but the dumb…

Strauss is supposed to be childlike, overly possessive, and just a complete fool. Yet, Strauss’ leer and ominous intonations just about give the twist away. And what can you say about the supposedly unsettling twist ending? Sorry, but I laughed.

Meanwhile, Francis’s four-year battle with lung cancer and her death in 2011 are covered in exactly one paragraph.

The tragically missed opportunity here, of course, is that Wagner chose not to talk to any of the dozens of co-workers or relatives who might have offered a peek at the real Anne Francis. (There’s one odd and somehow appropriately irrelevant exception: novelist Gloria Fickling, the co-creator of the Honey West character, who had little to do with the television series). Francis’s Forbidden Planet co-stars (at least four of whom outlived her) and John Ericson, her Honey West leading man, are particularly important sources who go unqueried. The reasons behind Francis’s firing from Riptide are not explored, even though Jo Swerling, the producer cited as having given the pink-slip to her agent, is still around. And what about Donnelly Rhodes – still living and working in Vancouver when Wagner’s book was published – or some of the men Francis dated during the second half of her life? Francis’s daughters are not hard to find and, amazingly, Dr. Robert Abeloff still lives and practices in Beverly Hills. How could Wagner resist asking how a dentist seduced one of the most desirable movie stars of her generation?

Wagner does not make a case for her hands-off approach in her introduction but, whatever the reasoning, I think it’s a terrible mistake. I once complained that one of Martin Grams’s encyclopedic tomes wasn’t a book, it was a file cabinet. Less ambitious, equally flawed, Anne Francis: The Life and Career isn’t a biography; it’s just a clipping file.

April 23, 2013 at 10:45 pm

Well, I’m sold…the Denham sounds like the more amusing and far less frustrating reading experience…