The Fabulous Career of Stanley Chase

October 14, 2014

Today’s New York Times has an obituary for Stanley Chase, a producer best known for mounting a key Off-Broadway production, a staging of The Threepenny Opera that ran for six years in the late fifties, and for the terrific science fiction film Colossus: The Forbin Project. The Times also credits Chase as a producer of television’s The Fugitive and Peyton Place, and for Bob Hope Presents The Chrysler Theater, specifically of that series’ Emmy-winning adaptation of Solzhenitsyn’s “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.”

But those television credits are largely inaccurate.

Chase did not produce either The Fugitive or Peyton Place, and his brief stint on The Chrysler Theater post-dated “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” by several years. The Times records that Chase launched The Threepenny Opera from a phone booth in a Manhattan cafeteria, and one must wonder if the newspaper has fallen for the sort of resume puffery that one might expect from such an intrepid hustler. Did the Times‘s latest round of layoffs include all the fact-checkers?

Here is a more accurate rundown of Stanley Chase’s career in television.

Chase graduated from New York University in 1949 and claimed (in 1955 and 1958 biographies that appeared in programs for The Threepenny Opera) to have founded and edited a “TV trade weekly” called Tele-Talent. The same biography places Chase on the staff of Star Time, a DuMont variety show that ran from September 1950 to February 1951, as a writer and associate producer. At some point between 1951 and 1954, Chase worked for CBS, where he met Carmen Capalbo, who would become his producing partner on The Threepenny Opera. The Times obit and other sources describe Chase as a story editor for Studio One, at the time CBS’s most prestigious dramatic anthology; the Threepenny Opera bios claim only that Chase worked in the CBS story department for “a number of years.” Studio One had no credited story editor prior to Florence Britton (starting in 1954), and a 1962 Back Stage article characterizes Chase’s role in slightly more modest terms: he “was a script consultant to the CBS-TV story department and assisted with such shows as Studio One, Suspense, and Danger during 1952 and 1953.” A profile of Chase by Luke Ford (author of The Producers: A Study in Frustration), based on Ford’s interview with Chase, offers an even humbler description of Chase’s CBS job (at least at the outset): messenger.

During the run of The Threepenny Opera, Chase produced three plays on Broadway and a Harold Arlen musical, Free and Easy, which closed after a European tour in 1960. After that, and a failed road company of The Threepenny Opera, he turned his attention again to television. In 1962, through his company Jaguar Productions, Chase developed a pilot that ended up at United Artists Television; called Dreams of Glory (and later retitled Inside Danny Baker), the proposed series was based on cartoons by William Steig (the creator of Shrek) and scripted by a pre-The Producers, pre-Get Smart Mel Brooks, at the time best known for his 2000 Year Old Man routine with Carl Reiner. According to UCLA’s catalog record for Inside Danny Baker, Chase shared a creator credit with Brooks, a configuration that would likely be prohibited under modern WGA rules. Chase told Ford that he and Brooks were sometime roommates, sharing an apartment in Manhattan and a Jaguar Mark IX in Los Angeles.

In May 1962, Chase joined ABC as a “director of programming development,” reporting to vice president Daniel Melnick. (Chase’s predecessor in that position: Bob Rafelson.) The Fugitive and Peyton Place were developed for ABC during Chase’s fifteen months as an executive at the network; but, significantly, those series were put together in Hollywood, and Chase was stationed in New York. Even if Chase did have some input, it’s far from customary for network suits to claim credit as producers. “We are looking for good shows and we’re working on some new ideas,” Chase told Back Stage in April 1963 – but just what ideas, exactly, seem to be lost to history.

In August 1963, Chase left ABC for a position as production executive for Screen Gems Television (still on the East Coast), where he developed a comedy pilot that would have been directed by Burgess Meredith and starred Zero Mostel. By the end of 1964, Chase was a free agent again, putting together another unsold pilot, Happily Ever After (renamed Dream Wife), starring Shirley Jones and Ted Bessell. Again, UCLA records Chase as a non-writing co-creator, alongside comedy writer Bob Kaufman.

In 1966, Chase – having finally relocated to Los Angeles – signed on with Universal, where he was assigned to the prestigious but fading filmed dramatic anthology Bob Hope Presents The Chrysler Theater. Chase came on the series at the tail end of the third season, and went into the show’s final year as one of four alternating producers under executive producer Gordon Oliver. The original group reporting to Oliver consisted of Jack Laird, Gordon Hessler, Ron Roth, and Chase; later Bert Mulligan and Paul Mason joined or replaced them. As if that weren’t fragmented enough, the twenty-six segments of Chrysler‘s fourth season included at least six produced outside of Oliver’s unit. It is possible that Chase worked on fewer than half a dozen episodes.

The five Chrysler episodes that I can confirm as produced by Chase are: “The Faceless Man” (an unsold pilot for a Jack Lord espionage drama called Jigsaw, later expanded into the theatrical feature The Counterfeit Killer; and yet again, Chase appears to have added his name to that of the pilot’s writer, Harry Kleiner, as a co-creator); “Time of Flight,” a Richard Matheson script with elements of science fiction; “A Time to Love,” an updating of Henry James’s Washington Square into a “jet age love story set in Malibu Beach” (New York World Journal Tribune) starring Claire Bloom and Maximilian Schell; “Verdict For Terror”; and “Deadlock,” an adaptation of an Ed McBain story that was the final new episode to air. “Time of Flight” was also a pilot, in contention as a series (to star Jack Kelly) for the 1967-68 season – and once again, per Billboard, Chase managed to couple his name to Matheson’s as a co-creator.

(“One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” was not one of Chase’s episodes: It was made in 1963, when Chase was still at ABC, and bears the creative stamp of Chrysler‘s original producer, Dick Berg. The teleplay for “Denisovich” is credited to Chester Davis – a pseudonym for screenwriters Russell Rouse and Clarence Greene – and Mark Rodgers, an ex-cop who was a protege of Berg’s.)

Joseph Sargent, the director of “Time of Flight,” also directed the two features that Chase produced for Universal following the demise of Chrysler: the quickie The Hell With Heroes and Colossus, which began gestating as early as April 1967, when Chase hired James Bridges to adapt the D. F. Jones novel upon which the film is based. Chase also developed another feature, a rock musical with tunes by Jim Webb, that never got off the ground, and optioned Matheson’s novel Hell House, with Richard C. Sarafian slated to direct. (The precise timing of the latter effort is unclear, but it had to fall between “Time of Flight” and The Legend of Hell House, director John Hough’s 1973 version of the Matheson novel.)

Chase was often at odds with the studio over Colossus, which was shot on a relatively modest budget ($2 million) but languished in post production for eight months of special effects tinkering. Universal execs had no faith in either the no-name cast that Chase insisted upon or the title, which it changed from Colossus 1980 to simply The Forbin Project (Chase: “probably because someone in a black suit out there thought Colossus sounded like a Joe Levine epic” – which it does, admittedly). At the producer’s prodding, the film finally crept into theaters for a New York test run in April 1970, but not until after a mortified Chase saw it playing as the in-flight entertainment during a commercial flight.

Good reviews led to a wider release for Colossus in the fall, more than a year and a half after principal photography, by which time Chase – vindicated, but perhaps with too many burned bridges behind him – had left Universal. Chase formed an independent company and optioned Stephen Schneck‘s cult novel The Night Clerk in 1971. That film was never made, but Schneck worked as a screenwriter on at least two of the offbeat features Chase produced in the seventies, which include: Peter Sasdy’s Westworld knockoff Welcome to Blood City; the Peter Fonda trucker opus High-Ballin’; and Donald Shebib’s Fish Hawk, which unfortunately is not about a creature that’s half-fish, half-hawk. (Will Sampson plays the title character, a Native American.)

Chase also produced movies for television, including Grace Kelly, a foredoomed biopic with Cheryl Ladd as the movie star princess; An American Christmas Carol (yes, the one with Henry Winkler); The Guardian, a critique of vigilantism written by William Link and Richard Levinson; and one of the most significant telefilms of the seventies: the Emmy-winning Fear on Trial, about radio personality John Henry Faulk’s lawsuit to expose the blacklist.

Chase’s papers reside at UCLA, and its finding aid contains a biography that is more fact-oriented than the Times‘s (although its chronology is slightly garbled). The UCLA biography reports that Chase was born Stanley Cohen, suggesting yet another inaccuracy in the Times obit, which claims that the producer’s parents were named Hyman and Sarah Chase.

In all, Chase’s career in television was far from undistinguished. It just doesn’t bear much resemblance to the one that the Times describes.

How Long Is Yours?

February 20, 2014

On Monday The A.V. Club ran a piece called Beyond True Detective: 17 Long Takes Worth Your Attention, to which I contributed two capsules. They aren’t bylined individually, but I wrote the bit on the John Frankenheimer Climax episode and the one on Peyton Place, in which I managed to work in yet another plug for the amazing imagery of episodic director Walter Doniger.

This article was inspired by a single, climactic shot in the fourth episode of the HBO drama True Detective. That shot garnered a lot of attention: it staged a complex, six-minute action sequence without a single cut, and it went “viral” in a way that was a little surprising. For most of the year television critics usually can’t be bothered to focus on television as a visual medium: it’s all plot, plot, plot, and occasionally some notes on the acting. All of a sudden, we spent a week thinking about television formally.

As encouraging as that is, it has a down side. For one thing, we’re not even used to talking about the form of television. The A.V. Club piece is a case in point: even after some useful dickering on Twitter over the distinctions between a long take and a tracking shot and a handheld or Steadicam shot and a sequence shot (the most accurate term for what was being listed there, although it’s not used much outside of film school), someone made an editorial decision to use “long shot” as an umbrella term for all of the above. But “long shot” actually means something different: it describes an unrelated type of composition in which the camera is a certain distance from the subject of the shot.

As the tentativeness of the first paragraph suggests, it’s hard to pin down just what kind of long take we’re interested in discussing. A long take can also be completely static, and as such it’s likely to convey a very different (even diametrically opposite) meaning than the frenetic True Detective shot. In Frankenheimer’s Playhouse 90 “Days of Wine and Roses,” the scene in which the two principal characters fall in love runs for seven minutes and five seconds, with only a handful of subtle camera moves. The emphasis is on the actors; the purpose of the duration is let them perform without interruptions, and to prevent cuts from distracting viewers from the subtlety of their work. The True Detective-style long take poses a wholly different set of challenges for the actors, more technical than emotional: the priorities are timing and hitting marks with precision. On Peyton Place, where Doniger tried on a regular basis to execute scenes in a single takes, the actors were sharply split in their preference for his method versus the more traditional approach of carving the action into smaller pieces.

When the subject of long takes in television first came up, I grew frustrated at how ill-equipped I was to write about them on short notice. I do have a personal roster of favorite early TV directors who regularly mounted this kind of ambitious, exuberant filmmaking within the tight time and money constraints of episodic television: not just Frankenheimer and Doniger, about whom I’ve written at length, but also sixties action masters Walter Grauman, Sutton Roley, and John Peyser. If I’d had better notes or more time, I would have loved to get in one of a handheld shot from one of Peyser’s (or Vic Morrow’s) Combat episodes, or a tracking shot from a Mannix or a QM show signed by Roley. And I didn’t recall until the eleventh hour the fondness that Elliot Silverstein expressed for long takes when I interviewed him. Silverstein described a long, complicated master that he did for Dr. Kildare – and his fury when he discovered that the editors inserted freeze-frames into it, in keeping with the show’s house style for its opening act credits.

Long takes were rare in early filmed television, because of the kind of obstacle Rosenberg encountered. Producers often competed with their directors for control over how a show looked. Even if a director staged scenes in a single master, the producer and the editors could cut away from it in post production. To ensure that a long take (or any other kind of adventurous set-up) was the only take that could be used, a director had to be forceful enough to resist a producer’s or a studio’s demands for more coverage (that is, more shots of the same action from different angles). Silverstein made a concerted effort to insert himself into the editing process (the DGA guaranteed a TV director’s right to supervise the initial cut of his episodes), but he was an exception. Apart from the question of whether or not the director was welcome in the editing room, many directors simply couldn’t afford to pass up an assignment on another episode just to hang around the editing room on the previous one.

Originally, I opened that blurb on Climax with this quote from Frankenheimer: “What can I do that’s going to be startling, that’s going to call attention to this show as opposed to every other piece of crap they’ve done on this thing?” What’s significant about that line is Frankenheimer’s bluntness about using the long take purely as an attention-getting device – a stunt. Confronted with material he didn’t like, Frankenheimer chose to overpower it with style. When I polled a few colleagues about possible shots to use in this discussion, Jonah Horwitz (a PhD candidate specializing in film and early television at UW-Madison) took issue with the whole premise. “I find the whole ‘my long take can beat your long take’ topic macho and boring,” he wrote. Long takes can be a kind of dick-measuring contest between competitive, egocentric filmmakers (a description that certainly applies to the live TV anthology group). The more complex the shot, the more it invites a spectator to disengage from the art and marvel at the technique – which is exactly what happened with that True Detective shot. As with many of Breaking Bad’s stylistic choices, the goal seems to be awesomeness rather than rigor or seriousness.

But I don’t share Horwitz’s exasperation with long take mania, and not just because I enjoy the most gonzo shots as their own spectacle. Another contributor to the A.V. Club piece mentioned “The Stingiest Man in Town,” the Alcoa Hour Christmas story directed by Daniel Petrie, and wrote this: “Many programs in the Golden Age Of Television were filmed in long takes for one simple reason: Filmed live as they were, editing had to be kept at a minimum, and anything too complicated (such as a massive musical number that also wanted to give close-ups of the singers) had to be carefully choreographed, the actors and cameramen moving in tandem with each other to achieve the maximum effect.” The problem with that is the part about editing. While there were some limitations (like studio space) that made long takes appealing to live television directors, editing wasn’t one of them. Directors understood quickly how much of their power to guide the viewer’s eye across a small, monochrome screen came out of those cuts from one perspective to another. And cutting stroked the ego as much as any showy long take: no director ever felt more directorial than when he was standing in the control room, snapping out the show’s rhythm with his fingers as he called out each cut from one camera to another: “Take one, take two, take one, take three….” The conditions of live television were more hospitable toward long takes than they were on film, and they are common on Danger and Climax and to a lesser extent Playhouse 90. But the long take was never a default mode in anthology drama – it was always one of an array of stylistic choices.

The popularization of the Steadicam in the eighties meant something of a resurgence in long takes on television (as it did in the cinema, where Scorsese and DePalma fetishized them). If handheld photography had originally been a consistent stylistic component mainly in series like Combat and The Senator, which cultivated a documentary-style realism, the Steadicam made it possible for handheld work to be more smoothly integrated with fixed-camera shots. Steadicam photography was faster and more versatile than tracking shots could be; most television shows’ sets weren’t built to accommodate the laying of track or the passage of the camera through every nook and cranny. (If you study the Walter Doniger sequence that’s embedded in the A.V. Club piece, you’ll notice that the camera doesn’t actually have the mobility to follow the actors very far into the set. Doniger covers for that limitation ably with a lot of lateral movement, and by pushing in and out repeatedly.) Director Thomas Schlamme’s fabled “walk and talk” aesthetic, tailored to put Aaron Sorkin’s verbose dialogue on its feet, defined The West Wing and has carried over somewhat into Sorkin’s current endeavor, The Newsroom, via Greg Mottola and other directors. And John Wells, the perennially underrated auteur who succeeded Sorkin as The West Wing’s showrunner, has made even more extensive use of the long-take Steadicam look, which became ER’s signature technique for conveying the bustle of a busy hospital. Wells’s Third Watch did an episode in which each act was a single take. The A.V. Club piece, and some of the readers’ comments, cover these recent works in detail. One of the unstated takeaways from that list is, perhaps, that that one True Detective isn’t such a big deal after all.

My first piece for The AV Club ran last Friday. It’s a look at the ritual of preempting or editing television shows in the aftermath of tragedies like the Boston Marathon bombing – a ritual that extends back at least as far as the murder of John F. Kennedy. (That’s Martin Milner above, in the strange Route 66 episode “I’m Here to Kill a King,” which was meant to air on November 22, 1963, and bears some disturbing parallels to the assassination.)

As I was researching the aftermath of President Kennedy’s assassination, I noticed that the original broadcast dates for at least two of the preempted television episodes have been recorded incorrectly in nearly every reference source. Presumably that’s because historians consulted newspapers’ TV listings without discovering that sudden changes were made after the listings were published. As a sort of wonky footnote, I thought I would untangle those errors here.

Channing, the one-season college drama with Jason Evers and Henry Jones, had an episode entitled “A Window on the War” slated for November 27, five days after the president’s death. An early work by the noted screenwriter David Rayfiel, who was adapting his play P.S. 193, “A Window on the War” involved an adult student’s plot to kill a professor (who is sort of a variation on the teacher character in All Quiet on the Western Front). The subject matter led ABC to push the episode back two weeks, to December 11. The episode that was substituted was Juarez Roberts‘s boxing story “Beyond His Reach,” which had evidently been penciled in for December 11. Wikipedia supplies the correct dates but the Internet Movie Database and the Classic TV Archive still have it wrong.

The Alfred Hitchcock Hour had planned to show “The Cadaver,” a Michael Parks-starring episode about a practical joke involving medical students and a cadaver, as the first post-Kennedy episode, on November 29. Instead, the episode that had been preempted on the night of the assassination, “Body in the Barn,” was shown on November 29, and “The Cadaver” (evidently because of its morbid subject matter) was pushed back until January 17. Most references claim that “The Cadaver” aired as scheduled on November 29 and that “Body in the Barn” didn’t resurface until July 3, in the middle of summer reruns. That’s wrong.

What’s interesting here is that, in their book The Alfred Hitchcock Presents Companion, Martin Grams Jr. and Patrick Wikstrom figured this out and printed the correct dates, with an explanation as to why they were given incorrectly elsewhere. That book was published in 2000, and yet all of the data aggregation sites on the internet – the IMDb, Wikipedia, TV.com, Epguides, the Classic TV Archive – still reflect the incorrect dates. It’s a good example of how sites like those tend to grab the low-hanging fruit and overlook more obscure sources. Rely upon them at your own peril.

As documentation, I’ve reproduced some pages from some relevant TV listings below. First, an early Los Angeles Times listing for Channing‘s “A Window on the War” on November 27:

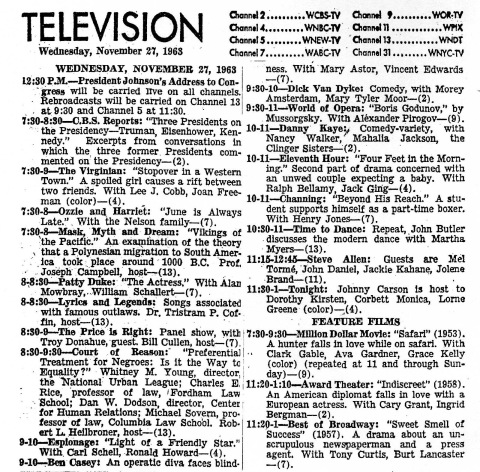

Then a New York Times listing for November 27, giving the evening’s episode correctly as “Beyond His Reach”:

A Chicago Tribune listing for “A Window on the War” on its eventual broadcast date, December 11:

A Hartford Courant listing for The Alfred Hitchcock Hour‘s “Body in the Barn” on its original airdate, November 29 (no date is given on the clipping, but the episode titles for other series correspond to 11/29):

“The Cadaver” debuting on January 17, 1964, per the Los Angeles Times:

This New York Times TV listing for July 3 is one of several that declares “Body in the Barn” a repeat:

Also in the AV Club article, I mentioned that Espionage switched around its schedule in order to delay an assassination-themed story. That episode was “A Camel to Ride, a Sheep to Eat,” which was pushed back from November 27 to December 18. “The Light of a Friendly Star,” originally scheduled for December 4, was moved up a week. I’m not sure of the original sequence for the episodes in between, but the Classic TV Archive has the final airdates right. (Apropos of nothing, can I tell you how annoyed I am that the British DVD release of Espionage went out of print before I snagged one?)

Black List, White Wash

May 8, 2012

Last month, in a buffoonishly McCarthyesque moment, Representative Allen West (R-Fla.) claimed in a town hall meeting that there were “about 78 to 81” communists in the United States House of Representatives. Asked to support that claim, West’s office could provide only some qualified (and unreciprocated) statements of support for the Congressional Progressive Caucus that appeared in a Communist Party USA publication. The Communist Party itself confirmed that it lists no members of Congress in its membership rolls. (If only….)

Also last month, a post on the UCLA Library Special Collections Blog announced that it has made available the papers of television pioneer Roy Huggins. The headline of the post characterized Huggins as a “blacklisted writer,” and the article went on to offer a description of Huggins’s relationship to the blacklist so artfully sanitized that it deserves to be called Orwellian:

In September of 1952, Huggins was summoned before the infamous U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) to answer questions about his brief membership in the Communist Party. He continued to write under his own name, and under the name “John Thomas James,” combining the names of his three sons.

It would seem that, more than two decades after the demise of the Cold War and the end of anti-communist hysteria, the subject still encourages the most basic and blatant distortions of fact.

*

Roy Huggins was a gifted television producer. With Maverick, The Fugitive, and The Rockford Files, all of which were largely his conception, Huggins proved that ongoing television series could defy genre conventions – could have authority figures as villains and defiers of authority as protagonists – and still attract an audience. The other series that bore Huggins’s imprint – 77 Sunset Strip, Run For Your Life, The Outsider, the Lawyers segments of The Bold Ones, Alias Smith and Jones – were less adventurous, but were consistently smart and well-produced.

Roy Huggins was also a fink.

On September 29, 1952, Huggins appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee and gave the names of nineteen colleagues and acquaintances whom he believed to be present or former members of the Communist Party. He gave the names with the full knowledge that, if they hadn’t been already, the careers of those men and women would be destroyed.

Huggins stood behind the defense that all of the names he supplied were already known to the Committee; in other words, he wasn’t fingering anyone whose life hadn’t already been wrecked. Huggins even worked that rationalization into his testimony (which is fascinating to read), although it does not bear up under scrutiny: if the handy appendix in Robert Vaughn’s Only Victims is accurate, Huggins was the only witness to name the optometrist Howard Davis in public testimony, and a few of the other eighteen were fingered in the HUAC record for the first time by Huggins (and then subsequently repeated by other friendly witnesses).

And of course, as Huggins later articulated, the actual names were irrelevant. HUAC was not interested in the names (which its investigators, and the FBI, already had); it was interested in legitimizing itself through the ritual of naming. Anyone who gave names bolstered the witchhunters’ influence, and prolonged the blacklist for everyone. Huggins thought he was beating HUAC at its own game (not just in his choice of names, but through several more arcane gambits that I haven’t gone into here). But, in the end, the House won.

It’s not my desire to rake Huggins over the coals again. Huggins himself was blunt, and repentant, on the subject of HUAC. In an eloquent interview in Victor Navasky’s Naming Names, Huggins called his cooperative testimony “a failure of nerve” and said that he was “ashamed of myself.”

The problem is that, no matter how much UCLA might like to, it is impossible to separate Huggins’s HUAC record from his later success. The inconvenient truth is that his career thrived during the era of the blacklist. Maverick, 77 Sunset Strip, and even The Fugitive came about during the decade when anyone who defied HUAC could not work in Hollywood. Had Huggins chosen not to give names, none of those shows would exist.

So, if we return to that post on the UCLA blog, some annotation is in order. In no way was Huggins a “blacklisted writer.” He has screenwriting credits in every year between 1948 and 1953, and directed a film, Hangman’s Knot, which was released in late 1952. Huggins worked steadily before the HUAC subpoena arrived, and his cooperation was immediate (or very nearly so). Some of the “late friendlies” were in fact sad figures who endured years of unemployability before finally capitulating to HUAC (in other words, they could accurately be described both as blacklisted and as friendly witnesses), but Huggins was not one of these. It is an insult to anyone who truly was blacklisted to apply the term to Huggins.

Further, the placement and wording of the UCLA post’s discussion of Huggins’s pseudonym implies that, like many authentically blacklisted writers, Huggins had to write under a false name during the Red Scare. In fact, he didn’t start using “John Thomas James” until the mid-sixties, and for reasons that had nothing to do with the blacklist. (Huggins described the pseudonym, which he often used on stories that were fleshed out into teleplays by other writers, as an act of modesty. A few writers I’ve talked to have suggested that Huggins was a credit grabber, and used the pseudonym to make it less obvious.)

It would be bad enough if some random blogger on the internet (like me) got these facts wrong. For an academic institution like UCLA to whitewash history in this way is inexcusable – particularly since the same misinformation (or disinformation) has also been recorded for posterity in the library’s official finding aid for the Huggins collection. This post – which is bylined by Peggy Alexander, a Performing Arts Special Collections Librarian at UCLA – betrays either an embarrassing ignorance of its subject or, perhaps, an even more dismaying inclination to obscure the facts and to rehabilitate Huggins for later generations who have (fairly or not) come to view the friendly witnesses as cowards and opportunists. If it’s the latter case, then UCLA shows incredibly poor judgment. Since when is it the job of libraries to act as press agents for its depositors? Not to mention that Huggins himself was frank about his role in the blacklist. Why should the curators of his legacy be any less so?

And finally, I submitted an early draft of the above as a comment on the UCLA blog last week. As of now, it is still “awaiting moderation” and not visible to the public. I guess that’s the internet version of getting gaveled down by J. Parnell Thomas.

Edited slightly for clarity on 5/9/12 – SB.

Corrections Department #8: Marion Dougherty, or: Math Is Hard!

December 9, 2011

Yesterday’s New York Times has an obituary for Marion Dougherty, an influential casting director who spent nearly two decades working in television before transitioning into feature films (including many important ones, such as Midnight Cowboy and The Sting).

It seems to be par for the course that television is a minefield even the most experienced obit writers can’t get right. Actually, the Times has already issued a correction with regard to Dougherty’s movie credits – initially the writer, Dennis Hevesi, added two films that she didn’t cast, Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate, to her resume. But I’m guessing we won’t see a correction addressing the two pretty obvious errors I spotted with regard to Dougherty’s television work.

The first suggests that Route 66 and Naked City, the two shows that really put Dougherty on the map as a discoverer of important talent, ran from 1954 to 1968. If only. The correct dates are 1960 to 1964. (Dougherty didn’t work on the earlier 1958 season of Naked City, which was cast less imaginatively by a West Coast has-been named Jess Kimmel). Although Dougherty had cast Warren Beatty on Kraft as early as 1957, it was on Naked City and Route 66 that she routinely gave early exposure to young Off-Broadway actors who would become some of the superstars of the seventies: Robert Duvall, Gene Hackman, Jon Voight, Cicely Tyson, Christopher Walken, Martin Sheen, Alan Alda, Bruce Dern, Ed Asner.

The second error is an internal contradiction: Hevesi writes that Dougherty was the casting director for Kraft Television Theater beginning in 1950 (I believe this is accurate, although it could be off by a year in either direction) but later claims that she was a casting assistant for six years. Since Kraft was Dougherty’s first job in the entertainment industry, and the series went on the air in 1947, that’s impossible. As far as I can determine, Dougherty started on Kraft in 1948 or (more likely) 1949, and became its chief casting director within two years or less. In any case, she was a woman well under the age of thirty when she started in that job – a noteworthy accomplishment, although there were other women with similar track records. (Alixe Gordin, who was born a year before Dougherty, became the casting director for Studio One around the same time Dougherty ascended at Kraft; Ethel Winant was a casting executive who achieved considerable prominence at CBS a few years later.)

Dougherty enjoyed a certain amount of public attention during this time – the Sunday Mirror Magazine ran a 1955 profile that called her “the nation’s top casting director” and credited her for sending Jack Lemmon, Rod Steiger, and Anne Francis to Hollywood – and her influence at Kraft cannot be underestimated. A blueprint of the offices of J. Walter Thompson, which packaged the anthology, places Dougherty in an office next to those of the two directors, Maury Holland (who was also the producer) and Fielder Cook; the three of them are the only Kraft staffers named on the plans. That Dougherty never received a screen credit on Kraft (her first, as far as I can determine, came immediately afterward, as the “talent coordinator” for the short-lived 1958 incarnation of Ellery Queen) was a noteworthy injustice, and probably one attributable to blatant sexism.

(At first Dougherty’s name was also absent from the credits of Route 66 and Naked City, although the executive producer, Herbert B. Leonard, eventually compensated for that omission by awarding her the humungous single-card credit shown above.)

Reading the Times article, one might get the impression that Dougherty was closeted. Actually the casting director, who kept her personal life very private, married during her Kraft years and later became the companion of director George Roy Hill (most of whose films she cast) after both their marriages ended.

In the interest of full disclosure, earlier this year I worked on a documentary, Casting By, which features Marion Dougherty prominently and identifies her as perhaps the first independent casting director, at least in the sense that that profession exists today. The Times does a good job of explaining her significance, but there is a lot to Dougherty’s story that remains untold. Sometime soon, I’ll write more about her.

Correction, 12/16/2011: An earlier draft of this piece indicated that Dougherty was married to the cult character actor Roberts Blossom; in fact, although Dougherty cast Blossom in several projects, her husband was a non-actor with a similar name. The Classic TV History Blog regrets the error (and acknowledges the irony of its appearance in a post that was itself a correction of another publication’s mistakes).

Corrections Department #7: Cliff Robertson and The Hustler

September 15, 2011

When Cliff Robertson, one of sixties television’s most persuasive and sought-after leading men, died over the weekend, I noticed a factual inaccuracy repeated in several obituaries, most prominently the Washington Post’s. As we’ve seen in earlier cases, like that of Sidney Lumet, otherwise impeccable obituarists tend to get their feet tangled in the murk of early television. Let’s set the record straight on this one.

Robertson’s most famous film role, at least at one time, was the one for which he won an Oscar – Charly (1968), the mentally retarded man made super-smart by science, which he had first played in a 1961 United States Steel Hour called “The Two Worlds of Charlie Gordon.” In its obituary for Robertson, the Post set the stage for Charly with these paragraphs:

While acquiescing to studio demands in a run of undistinguished films, Mr. Robertson found more compelling work on live television. He played a pool shark in “The Hustler” and a married alcoholic in “Days of Wine and Roses.”

When it came time to cast the film versions, he was overlooked in favor of bigger stars: Paul Newman and Jack Lemmon, respectively. “I was starting to get a reputation as always a bridesmaid, never a bride,” Mr. Robertson said decades later.

It’s a catchy factoid: Robertson, the perennial also-ran, loses out on not one but two key film roles he had originated on television, then wises up and buys the movie rights to a third, to great triumph. But it’s wrong.

Robertson did give an extraordinary performance in the Playhouse 90 broadcast of “Days of Wine and Roses.” But Robertson was not in the live television version of The Hustler. In fact, there was no live television version of The Hustler.

Walter Tevis first wrote the story of pool shark Fast Eddie Felson as a Playboy short story in 1957, turned it into a novel two years later, and saw the Paul Newman film come out two years after that. No video incarnation was produced during that four-year stretch.

So from where did this persistent bit of misinformation originate? Possibly from Robertson himself. In Shoptalk: Conversations About Theater and Film With Twelve Writers, One Producer – and Tennessee Williams’ Mother (Newmarket, 1993), Robertson told author Dennis Brown that

Back in the late 1950s I did several shows on live television, things like Days of Wine and Roses and The Hustler, that went to other actors when they were made into movies. I came to the conclusion that in order to get a great role, I had to develop it for myself.

Was Robertson inventing his association with The Hustler – embellishing his resume with a role he didn’t get? No, but he was stretching the truth a bit.

Robertson did star in a television anthology segment about a nervy young pool hustler who faces off against a fat, cocky old pro (Harold J. Stone). The show was called “Goodbye, Johnny,” and it was first aired on Alcoa Theatre on February 9, 1959. But “Goodbye, Johnny” was shot on film, not broadcast live; the characters’ names are all different from those in The Hustler; and Walter Tevis’s name appears nowhere in the credits. A number of reference books have identified “Goodbye, Johnny” as an adaptation of The Hustler, but that’s plainly inaccurate. The only connection that one might establish between them would be a charge of plagiarism against the writer of “Goodbye, Johnny,” Leonard Freeman. (I’ve seen both the film and the television episode, but not recently enough to take a position on that subject; and I haven’t read either the short or the long version of Tevis’s text.)

Clearly Robertson felt there was a link between “Goodbye, Johnny” and The Hustler. That’s probably because Robertson auditioned unsuccessfully for the role of Fast Eddie Felson; and, according to at least one source, it was “Goodbye, Johnny” that got him that audition. So maybe for Robertson, Johnny Keegan really was just the TV version of a movie role he never got. But for the rest of us, it’s just sloppy fact checking.

As a postscript: I greatly enjoyed learning, as I researched this piece, that our new friend Gerald S. O’Loughlin played a pivotal role in the Charly story, and that Robertson was a big fan of his. O’Loughlin was in the cast of “The Two Worlds of Charlie Gordon,” and, as Robertson tells it in his Archive of American Television oral history,

Gerald O’Loughlin had a profound impact. He was one of the wonderful character actors; still is. We were doing the TV version of Charly . . . and he said to me, in the middle of the week, “Cliff, you’re doing a hell of a job. Who do you think’ll do the movie?” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “Well, you know, every time you do a good job on television, whether it’s Days of Wine and Roses or what, some movie star comes along and buys it or gets it and you’re watching it and you’re not [in it]. Who do you think’ll get the movie?” And I said, “Well, knowing Hollywood, maybe Debbie Reynolds,” just to be kidding. So that was Gerry O’Loughlin, also a member of the Actors Studio. Great actor.

*

And one more for the road: The Los Angeles Times claims that thirty-year All My Children star Mary Fickett, who died on September 8,

found steady work in television in the 1950s and ’60s, including the anthology programs “Kraft Theatre,” “Armstrong Circle Theatre” and “The United States Steel Hour,” as well as “The Edge of Night,” “The Nurses” and other prime-time series. When “The Nurses” was turned into a daytime drama in 1965, she continued her role.

Wrong: Fickett was a guest star on a 1963 episode of the prime-time The Nurses called “A Dark World,” playing Karen Gardner, a nurse who transfers to the psych ward as part of the recovery process from her own breakdown. (Ah, medicine!) When she joined the daytime The Nurses in 1965, Fickett took over the leading role of senior nurse Liz Thorpe from the original star, Shirl Conway.

Corrections Department #6: Stryker Redux

April 5, 2011

Yes.

No. At least, not quite.

Leslie Stevens took sole screen credit for directing Stryker, aka “Fanfare For a Death Scene,” the trashy Daystar Productions pilot we examined last month. However, Stryker shared an unfortunate fate with The Haunted, the other Daystar pilot I wrote about in that piece: both saw their original director fired and replaced by the producer, arguably to the detriment of the finished product. In fact, Stryker’s production proved far more chaotic than that of The Haunted.

The initial director of Stryker was actually Walter Grauman, a highly regarded episodic and telefilm director with a forceful, action-driven style and a resume the size of the phone book. Though his credits also include Matinee Theater, Naked City, and over fifty Murder She Wrote segments, Grauman was best known for his association with producer Quinn Martin. He established the look of The Untouchables, directed the pilot for The Fugitive, and helmed many episodes of QM’s later detective shows, especially The Streets of San Francisco and Barnaby Jones.

Grauman worked on Stryker for about half of its official production schedule, before Leslie Stevens, in his capacity as producer, fired Grauman and took over as director.

Initially, Grauman was hired to direct Stryker in July 1963, while he was on location in England directing the feature 633 Squadron. Stryker, set to start filming on October 7, was delayed for a week and a half, and then another six weeks, for reasons that are unclear. During the hiatus, Grauman directed a single episode of Burke’s Law, but nothing else that fall; likely the delay cost him work, as it was too late for Grauman to book any other jobs during the original shoot dates.

When filming finally began on December 9, 1963, Grauman’s original director of photography was a journeyman named Monroe Askins, whose most substantial TV credits were a number of cheap action shows (Highway Patrol, Bat Masterson, Sea Hunt) for Ziv. The pilot had a budget of $256,000 and a ten-day schedule, of which Grauman shot at least six days. Grauman directed interiors at the Goldwyn Studio (also home to The Outer Limits) and exteriors, all at night, on MGM Lot #2, the Bel Air Sands Hotel (off Sunset Boulevard next to the 405 Freeway), and the Huntington Hartford Theater (now the Ricardo Montalban Theater, on Vine Street between Hollywood and Selma).

(The Hartford Theater provided both the exteriors and interiors for the climactic concert sequence. The Bel Air Sands probably doubled for the exterior of Stryker’s apartment, and the MGM backlot – where most of the exteriors for The Outer Limits were staged – was likely the site for the opening scenes outside the asylum, among others.)

At the beginning of his second week on Stryker, Grauman reported to work for more location shooting at the Wilshire-Comstock Apartments in Westwood (later the site of Freddie Prinze’s suicide). Leslie Stevens was already there, and Grauman was informed that his services would no longer be needed. Askins was also replaced, by The Outer Limits’ primary cinematographer, Conrad Hall. Hall had just wrapped on “The Bellero Shield,” The Outer Limits’ final segment of the year before a two-week Chrismas hiatus, on December 16, and it is possible that his availability triggered the timing of the personnel changes.

Why was Grauman fired? We may never know: Grauman, apparently, was never fully informed, and Stevens died in 1998. The two men had never worked together before, and it is possible that Stevens took exception to some aspect of Grauman’s distinctive style. But Stevens, on Stoney Burke and The Outer Limits, favored directors who took visual chances, and who shared Grauman’s love of bold compositions and aggressive camera moves: Leonard Horn, Tom Gries, Paul Stanley. Stevens himself worked that way. It is hard to fathom any obvious aesthetic clash between the two men.

Here is a purely speculative hypothesis: that Stevens saw the first week’s rushes, recognized the deficiencies in the script to an extent that he hadn’t before, and felt that the only hope for salvaging the turkey that was Stryker was to take the reins himself. But whatever Stevens thought he could add obviously didn’t help.

(A simple clash of egos is another possibility. Grauman and Stevens were both known as strong personalities.)

As Stevens struggled to assemble something usable out of the mess of Stryker, the pilot went over schedule and far over budget (Grauman estimated, perhaps too generously, a final tally of $1 million). In addition to finishing the script, Stevens reshot most of Grauman’s work. During a recent viewing of Stryker, Grauman recognized only some of the Huntington Hartford sequences as his own.

For Grauman, being fired represented a psychological blow, but not a major career setback. In January of 1964, he directed some of his finest work, the “Angels Travel on Lonely Roads” two-parter for The Fugitive (featuring Eileen Heckart as Sister Veronica, a performance so memorable that the character was brought back three years later) and a pair of Kraft Suspense Theaters. One of those, “Knight’s Gambit,” was a routine pilot that didn’t sell, but the other, “Their Own Executioners,” was an extraordinary sophisticated piece of work, featuring a script by Luther Davis (Grauman’s collaborator on his best film, Lady in a Cage) and a deeply moving performance by Herschel Bernardi.

*

One reason I filed this piece in the dreaded “Corrections Department” is that I committed a lazy gaffe in the original Stryker essay. I included the bumper-level shot of a car passing the camera in a list of typical Conrad Hall compositions, but in fact, it is a signature Walter Grauman shot; so much so that other directors I have interviewed have gently mocked Grauman’s fondness for low-angled framings of automobiles and buildings. I love these images – in an abstract way they express the prosperity, the urgency of the Camelot era – and they are very much Walter’s.

The camera starts below Richard Egan’s Lincoln Continental . . . and then tilts up to emphasize the enormity of his digs. I believe that Stryker’s office exterior, seen here, was actually the Wilshire-Comstock building, so this may have been one of the last shots Grauman completed.

Author’s Note: Although I have interviewed Walter Grauman on several occasions, we never discussed Stryker. Nearly all the information in this post, including the initial tip regarding Grauman’s involvement, was contributed by a fellow historian who prefers to remain anonymous. The contributor’s sources were his own interviews with Grauman, and Grauman’s papers at the USC Cinema-Television Library. His generosity in allowing me to publish this research is gratefully acknowledged.

Corrections Department #5: Two Cop Shows and One Missing Producer

September 22, 2010

The pilot of Hawk produced itself. At least, that’s what you’d think if you read the screen credits closely, and believed what you read. They list an executive producer (Hubbell Robinson), a production consultant (Renee Valente), and a production supervisor (Hal Schaffel). But no producer. Maybe that’s all you need to create a pilot; if the show sells, then you can find someone to put the show together every week. That’s what I thought, when I first transcribed those credits. But I was wrong.

Recently, I pulled the string on that missing producer credit. What unraveled was a story, in microcosm, of the corporatization of the television industry during the mid-sixties. Of how the last holdouts of the rough-and-tumble, just-do-it veterans of New York live television succumbed to the studio politics that emanated from the West Coast.

*

Let’s back up a minute. Maybe you’ve never heard of Hawk. If you weren’t around during the last seventeen weeks of 1966, or if you haven’t spend any of the years since surfing local New York-area reruns during the late-night hours, that’s understandable.

Hawk was a cop show that debuted on ABC on September 8, 1966. It had a simple premise. John Hawk (Burt Reynolds) was a tough young plainclothes detective who caught killers, thieves, and other felons. There were two gimmicks. One, Hawk was a full-blooded Native American. Two, he worked the night shift. Hawk never saw daylight, and neither did the viewer.

Let’s look again at the credits of the Hawk pilot, which was titled “Do Not Spindle or Mutilate.” Hubbell Robinson was one of television’s most respected independent producers, a former CBS executive whose championing of Playhouse 90 (which he created) and other quality television had damned him as, perhaps, too cerebral for the mainstream. The writer was Allan Sloane, a recent Emmy nominee for an episode of Breaking Point. Sam Wanamaker, who had spent his years on the blacklist as a distinguished Shakespearean actor in England, directed. Kenyon Hopkins, composer of East Side / West Side’s brilliant, Emmy-nominated jazz score, wrote the music, and The Monkees impresario Don Kirshner is in there as a “music consultant,” whatever that means. Oh, and the guest villain, the guy who bundles up a bomb in a brown paper wrapper before the opening titles? Gene Hackman.

And what about that missing name? He had some Emmys on his shelf, too. The producer of “Do Not Spindle or Mutilate,” the one who’s not mentioned in any reference books or internet sites, was Bob Markell, fresh off a stint producing all four seasons of The Defenders. The Defenders won multiple Emmy Awards every year it was on the air, including the statue for Best Drama (which Markell took home) during the first two seasons. Hawk was only Markell’s second job following The Defenders. So why was his name expunged?

“There are a lot of well-kept secrets about me,” said Markell in an interview last month.

*

It was Hubbell Robinson who hired Markell for Hawk (which may have originally been titled The Hawk). Markell had just produced a terrific one-off John D. MacDonald adaptation called “The Trap of Solid Gold” for Robinson. Ironically, “The Trap of Solid Gold” did not air on ABC Stage 67 until seven days after Hawk left the network’s schedule for good.

“Do Not Spindle or Mutilate” was already written by the time Markell came on, but the new producer liked Allan Sloane and his script. Markell hired Sam Wanamaker, who had guest starred on The Defenders every year and directed one of the final episodes. Markell wanted David Carradine to play John Hawk, but Carradine was already committed to Shane, a TV adaptation of the famous western that would, also ironically, depart from ABC’s schedule two days after the final broadcast of Hawk. It was a tough time for the old New York guard: the producers of Shane were Herbert Brodkin and David Shaw, respectively Markell’s old boss and story editor on The Defenders. Burt Reynolds was the second choice for the starring role. He came to the show via Renee Valente, a close friend who would work with Reynolds as a producer, on and off, for the next thirty years.

For the production crew, Markell reteamed almost the entire below-the-line staff from his old show. J. Burgi Contner, the director of photography; Arline Garson, the editor; Ben Kasazkow, the art director; future director Nick Sgarro, the script supervisor; Al Gramaglia, the sound editor: all came over from The Defenders. Markell and Alixe Gordin, the casting director, had used Gene Hackman more than once on The Defenders, and elevated him to a leading role for “Do Not Spindle.”

The physical production was difficult. Nighttime exteriors were extensive. “We didn’t have the budget to even get any lights to put up at night, and I still had to do the show,” said Markell.

Then came the real problems.

*

“We finished it and I thought we had done a super pilot. I really did,” said Markell,

and I delivered it to Hubbell. I got this call, and Hubbell said, “You’ve got to get on a plane. We’re taking the movie to Los Angeles.”

I said, “Why?”

“I can’t tell you,” he said. It was a big secret.

Allan Sloane asked, “Why are you going out there?”

I said, “Because they asked me to.”

When we landed, we were all going to the Beverly Hills Hotel, and Hubbell turned to me and he said, “Where’s the film?”

I said, “I gave it to Renee.”

He said, “You shouldn’t have given it to her. She’s now going to bring it to Jackie Cooper.” And then the politics began, you know.

At the time, Jackie Cooper – the former child actor and adult TV star – was the head of Screen Gems, the television unit of Columbia Pictures. It was Columbia that backed the Hawk pilot. Up to this point, Robinson had shielded Markell from studio interference. That was about to change.

On his second day in Los Angeles, Markell learned the reason for his secret visit:

They brought me to this black building with no name on it or anything. I said, “Why are we here?” I discovered it was for testing purposes. That was one of the first shows that were tested before an audience. This was highly secret. Nobody knew about these things.

They’d invite people from the street. The audience had these little buttons: yes, no, yes, no. Then they’d subsequently invite maybe eight or nine people to sit around a table. We’d be at a two-way mirror, and we’d listen to them discuss what they liked or didn’t like about the movie.

I sat with the guys with the dials, and I thought they might have a sense of humor, and I said, “You know, why don’t you take their pulse, and maybe their perspiration rate and things like that also to find out how they’re reacting?”

And they said to me, “We’re working on it.”

Joking aside, Markell felt that violence was being done to his work:

I was furious. I mean, I was really indignant. I was under the impression that the artist – and we considered ourselves artists – showed the public a new way to look at things, a new way to see things, a new way to hear things. We didn’t want their opinion, we wanted our own. We were the creative people. And I still believe that, by the way.

Markell called New York and reported this latest development to Allan Sloane. Sloane had been a worrier during production, calling Markell all the time to ask whether his intentions were being realized on the set. As Markell described it:

Allan and I would sit, and I would agree with [him], because I loved writers: “Yeah, don’t worry about it, they’re doing it the way you would like them to do it.” I was kind of consoling him. Actually, often I didn’t tell him the truth, but that was all right.

With Screen Gems now threatening to tamper with the pilot, Markell had to calm his writer down all over again:

Allan Sloane was hysterical. He was in New York, and he said, “I’m going to blow it. I’m going to blow this story. I’m going to tell Jack Gould [the powerful New York Times television columnist].”

I said, “Allan, wait, see what happens.”

We came back the next morning. Jackie Cooper – I swear to you this is a true story – rolled out what was the equivalent of a cardiogram of the show. Horizontal line, up, down, up, down, up, down. He said, “Now, look at it. If we can get rid of those downs, we’re going to have a great show!”

I said to him, “If you get rid of the downs, you don’t have any ups. You’re going to have just a straight line. You’re not going to have ups without downs.”

And as another joke, I said, “How did the credits do?”

“Oh, no, don’t touch those. Those were great.”

Markell had had enough:

We had booked a flight for that afternoon. I turned to Hubbell and I said, “I’ve got to make that plane, Hubbell. My wife, the kids, I’ve got young children. I’ve got to leave. I’m sorry to leave this meeting, but I’m going.” And I left the meeting.

Renee ran after me and says, “You’re killing your career.”

I said, “Renee, I can’t handle this. I cannot be a part of this.”

I mean, if I’m going to have to sit and listen to what some guy off the street thinks, and then have to defend myself . . . . So I went home.

Allan Sloane could not contain himself. “Allan called Jack Gould, and Jack Gould had a huge thing about how we were secretly testing all of these shows, and it’s no longer the artist’s creative thing,” said Markell. “Everybody was furious because Allan blew the story.”

*

Back in New York, Markell realized that he had no one in his corner. Renee Valente sided with power. Allan Sloane, like all writers, had no power. (He retained a “created by” credit on Hawk, although after his tip to the press he was not invited back to write other scripts for the series). On The Defenders Markell had both broken the blacklist for Sam Wanamaker, and given him his first shot at directing American television. “But I suddenly found I didn’t have a friend in Sam,” Markell revealed. “I have no reason why, but he was not about to do a show with me producing it. I was a fan of his, but there was a certain hostility.”

And at the top there was Hubbell Robinson. “Hubbell was getting older, and not as tough as he used to be,” Markell said. He wasn’t really surprised by what happened next:

I came back to New York and discovered that the show was picked up. And I was walking down 57th Street one day and Paul Bogart passed me. Paul said to me, “I’m producing the show.”

I said, “Oh. Obviously, I’m not.”

Paul said, “You know, I really had nothing to do with it.” Because we were also very close friends. There was a good spirit among the New York people. Paul said, “Is there anything I can do?”

I said, “How about you hiring me to direct them, then?” I didn’t really mean it, because I never really wanted to direct. And so the show started.

When “Do Not Spindle or Mutilate” was broadcast on September 19 as the debut episode of Hawk, Screen Gems had removed Markell’s name from it. Markell was not aware of that fact until I told him of it last month. “It’s too late to get angry,” he mused.

Bogart was a surprising choice to produce Hawk. At the time he was one of television’s most sought-after directors, another Emmy winner for The Defenders, but he had produced next to nothing. It’s possible Bogart was a political pawn, set up to fail. Renee Valente brought him in; still just a “production consultant,” she was technically hiring her boss.

Immediately, Bogart found himself right in the middle of the power struggle between Cooper and Robinson:

The producer was Jackie Cooper, and the top producer was Hubbell Robinson. Hubbell was a very distinguished old-timer. I met Jackie for lunch one day at the Oak Room at the Plaza. We were going to talk about the show, and he sat down and he said to me, “We don’t need Hubbell, do we?”

I didn’t know what to say to that. He got rid of Hubbell Robinson, just got rid of him. There was something really nasty going on there. I never knew all the facts.

Bogart enjoyed his new job at first. “It was fun, because it was a nighttime shoot,” he recalled. “I had an office on Fifth Avenue, at Columbia Studios, right across the street from some jewelry place that was wonderful to look at.” But he clashed with Burt Reynolds, and with his bosses at Screen Gems. Bogart initiated a story idea he liked, a “Maltese Falcon script” that pitted Hawk against a femme fatale character modeled on Brigid O’Shaughnessy (Mary Astor in the film). The executives didn’t like it. Then he approved a scene containing a strong implication that Hawk and the villainess (Ann Williams) had slept together. The executives really didn’t like that. Bogart wasn’t surprised that his head was the next to roll.

“They fired me eventually,” Bogart said. “I knew it was going to happen, but I didn’t want to just leave because I thought I would have some money coming if I just sat there until they made me go. I don’t think I got anything from them, but eventually I left.”

Bogart received a producer credit on exactly half of the Hawk segments made after the pilot. The remaining eight, like “Do Not Spindle or Mutilate,” do not list a producer on-screen. It is possible that Cooper and Valente produced the final episodes themselves. By then Hawk had acquired a story editor (Earl Booth), an associate producer (Kenneth Utt), and a “production executive” (a Screen Gems man named Stan Schwimmer), so maybe at that point it really could produce itself.

(Although his name does not appear in the credits of any episode, some internet sources list William Sackheim as a producer of Hawk. This contention is within the realm of possibility, since Sackheim was producing sitcoms for Screen Gems at the time, but I can find no evidence to support it. According to Markell, Sackheim had nothing to do with the pilot for Hawk up to the point of Markell’s departure.)

*

At the same time Paul Bogart was falling out with the top brass at Screen Gems, Bob Markell landed his next gig:

Now come along David Susskind and Danny Melnick. They say, “We’re doing a show called N.Y.P.D., and we’d like you to produce it.” I said, “Okay.” This was simultaneously while the other show was shooting.

This time, Markell was the replacement. ABC had sent back the original hour-long pilot for N.Y.P.D., written by Arnold Perl and directed by Bernard L. Kowalski, for retooling. Everyone was out except for a few of the original cast. Kowalski told me that Robert Hooks and Frank Converse were the holdovers, with Jack Warden (as their lieutenant) coming in to replace a third young detective, played by Robert Viharo. Markell remembered it differently:

Danny said to me, “I want you to do a trailer for the new series, and we’ll probably get on the air.” I went to look at the pilot, and discovered that most of the people in the pilot weren’t in the show. Bobby Hooks wasn’t in the show, Frank Converse wasn’t in the show. I had to make a trailer around Jack Warden and do whatever I could.

Markell’s highlight reel sold the stripped-down N.Y.P.D. pilot to the network. Superficially, the new show was similar to Hawk. Both spilled out into the streets of Manhattan, updating the grimy, teeming urban imagery of Naked City and East Side / West Side with a burst of color. But Hawk courted a film noir sensibility – John Hawk was the lone wolf, hunting at night – and N.Y.P.D. was about the institution, the process. It followed three detectives of varying seniority as they plowed methodically through the drudgery of police work: legwork, surveillance, interrogation.

Markell was working for another tough boss, but loved his new cop show as much as the old one:

I loved doing N.Y.P.D. I was allowed to do all kinds of experimentation. We shot it in sixteen-millimeter, which nobody else ever did. When I went to ABC to ask permission to shoot it in sixteen, it was like James Bond going to the CIA. They said, “If you get caught, we don’t know you. But go ahead.”

David Susskind would sometimes, rightly, say, “This is a terrible [episode]. You guys, you Emmy winners, you Defenders guys, this is an awful show.” And he was right, most – some – of the time. He was a tough judge of the shows, and he kind of whipped us into shape, because we all sometimes had a tendency to get a little lazy. You know: “let’s get the shot.”

Every three days, or three and a half days, we shot a new show. The scripts would keep coming in. Did Eddie Adler ever tell you the story of how he stood in the middle of the road here on Long Island, and I went by and got his half of the script while Al Ruben wrote the other half of the script? It was like a spy drop. Eddie was standing in the road with an envelope. I would pick it up and I would go into the city.

But anyway, to finish the story about N.Y.P.D. N.Y.P.D. was picked up, and Hawk was dropped. And I was put into that timeslot. Which is my revenge.

That’s not quite accurate: Hawk ran on Thursdays at 10PM, N.Y.P.D. on Tuesdays at 9:30. But it seems likely that ABC had only one “slot” for a stylish Manhattan police drama on its schedule, and that N.Y.P.D.’s pickup had been contingent upon Hawk’s cancellation. And the network probably told Markell as much.

Sometime during the production of N.Y.P.D., Markell added,

I went to the theatre one night to see another version of The Front Page. I was sitting at one end of the aisle, and there was Burt Reynolds at the other end of the aisle. Now, I hadn’t worked with Burt except for the pilot, and we got along really great. Somebody passed his program along to me. I have it upstairs someplace. Written on the program was, “If you ever need to do a show about an Indian at night, please call me. I’m available.” That was really very sweet. I felt good about that. But we did replace Hawk, and lasted two years.

And this time, Markell got his credit.

Thanks to Bob Markell (interviewed in July 2010), Paul Bogart (interviewed in February 2009), and the late Bernard L. Kowalski (interviewed in January 2006).

After Allan Manings, a television comedy writer, died on May 12, the Los Angeles Times ran a medium-length obituary which offered an adequate summary of Manings’s career. The obit foregrounded some warm quotes from his stepdaughter, the actress Meredith Baxter, which I suspect would not have received as much prominence had Baxter not made news recently by revealing her homosexuality. What’s most interesting about Dennis McLellan’s piece in the Times, though, is what it left out.

Manings came to prominence late in life. In his mid-forties, he won an Emmy as part of the original writing staff of Laugh-In. In fact, according to an invaluable interview with Manings in Tom Stempel’s Storytellers to a Nation: A History of American Television Writing, Manings was the first writer sought out by Laugh-In’s creator, George Schlatter, to work on the show. Manings served as a head writer on the popular sketch show for four seasons, and was thought of (in Schlatter’s words) as the “conscience of Laugh-In,” because he fought more aggressively than anyone else to include political material in the show’s gags. When all ten of Laugh-In’s writers crowded on stage to accept their Emmy in 1968, it was Manings who quipped, “I’m sorry we couldn’t all be here tonight.”

After Laugh-In, Manings became a part of Norman Lear’s expansive sitcom factory of the seventies, helping to develop Good Times in 1974 and co-creating One Day at a Time the following year. Manings wrote One Day at a Time with his wife, Whitney Blake (Baxter’s mother), and the pair derived the show’s original premise from Blake’s own experiences.

The earliest of Manings’s credits cited in the Times obituary is Leave It to Beaver. Manings wrote two episodes of Beaver during its final seasons, and didn’t particularly care for the show; he was already looking ahead to the more realistic humor of the Lear era. (I had thought for a long time that Manings was the last surviving Leave It to Beaver writer, but I realize now that that distinction probably belongs to Wilton Schiller, a writer better known for his work on dramatic series like The Fugitive and Mannix.)

Leave It to Beaver was also Manings’s comeback from the blacklist, and that’s the conspicuous omission from the Los Angeles Times obit. Manings had gotten started in television writing a “few sketches” (Stempel) for Your Show of Shows and then joined the staff of one of its successors, The Imogene Coca Show, along with his then-writing partner, Robert Van Scoyk. After a year or two, Manings’s agent tipped him off that he’d become a political sacrifice, and Manings took refuge in a novel place: Canada. (Although many blacklistees went to England, Mexico, France, or Spain in search of work, I can’t think any others of note who spent their lean years in Canada.) Manings may have found some work in live television there, but after a time he ended up working on a forty-acre horse farm. Manings sold manure to other local farmers and realized, as he related to Tom Stempel, that Hollywood would pay more for horse shit. As soon as the blacklist began to thaw, Manings moved to Los Angeles.

(A footnote: In his interview with Stempel, Manings identified Beaver as the show that ended his exile, although Manings’s papers reveal that Ichabod and Me, a dud sitcom created by Beaver producers Joe Connelly and Bob Mosher, was probably his first post-blacklist credit, in 1961.)

Manings’s blacklisting is no secret, and I’m certainly not implying that some rightist conspiracy has suppressed the facts. Still, it’s curious that the Times steered so carefully around that portion of Manings’s biography. It seems doubtful that McLellan simply didn’t know about it, since his obit references Manings’s political activism more than once. There’s a quote from Lear about Manings’s commitment as a voter and a citizen, and Baxter describes him as “a very outspoken liberal.” Perhaps it’s just that the blacklist is old news these days, first to be sacrificed for length ahead of soft quotes from celebrities.

Ironically, in Stempel’s book, Manings chose to clam up about the blacklist, too. His only direct quote on the matter is: “I fronted for some, others fronted for me.” I’d always hoped for, but never got, a chance to press Manings further on the subject.

Last December, in this interview, Meredith Baxter discussed the reactions of some of her family members after she decided to come out of the closet. She mentioned her stepfather, although only by his first name, so I doubt that anyone realized (or cared) that she was talking about Allan Manings. But through her, Manings got in a marvelous last word.

“I went to Allan and I said, ‘I’m dating women,’” Baxter related. “And he said, ‘Hmm. So am I.’ And that was that.”

*

As long as this entry is getting filed under the Corrections Department, we may as well turn our attention to one David E. Durston, who also died this month. Durston is remembered mainly as the auteur behind the low-budget cult horror film I Drink Your Blood. I’ve never seen the movie, and I know little about Durston. Judging by his resume, as enumerated in this perhaps lengthier-than-deserved Hollywood Reporter obit, Durston seems to have been one of those figures who hovered on the fringes of the movie industry for decades, carving out a marginal career with an energy that surpassed his talent.

Picking on the recently deceased is a joyless exercise, but in the interest of the historical record, I have to call foul on this claim, quoted from the Hollywood Reporter but repeated in substance by many other sources: “Durston wrote for such ground-breaking TV shows as Playhouse 90, Rheingold Playhouse, Tales of Tomorrow – one of the earliest science fiction anthology shows – Kraft Theatre, and Danger.”

Resume padding is common in the entertainment industry (and everywhere else), and in the pre-internet days you could get away with it for a long time. When I interviewed one prominent writer-producer of the sixties and seventies, I asked him about the Philco Television Playhouse, which had turned up on some lists of his credits. Somewhat embarrassed, the man admitted that he had never written for Philco. When he was young and struggling, Philco (the anthology on which Paddy Chayefsky’s “Marty” debuted) was the most prestigious credit a television writer could have, so he simply added it to his resume. In his case, the chutzpah paid off. I think Durston may have tried the same thing.

A writer named Stephen Thrower, who interviewed Durston at length, has compiled the most detailed list of Durston’s credits that I can find. Note how it remains vague about the big dramatic anthologies – Danger, Studio One, Kraft Television Theatre, Playhouse 90. No dates, no episode titles.

Let’s start with the easy ones. Thrower’s resume for Durston lists four teleplays for Tales of Tomorrow, and three of those are confirmed in Alan Morton’s The Complete Directory to Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Television Series (Other Worlds, 1997). A fourth, “The Evil Within,” is credited on-screen to another writer, Manya Starr. Then there’s the Rheingold Playhouse – or, actually, there isn’t, because there was no Rheingold Playhouse. Durston may have meant this production, “A Hit Is Made,” which seems to have been a one-time live broadcast, sponsored by Rheingold Beer and telecast from Chicago in 1951. A few years later, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., hosted a dramatic anthology called the Rheingold Theatre, and by christening the earlier show the “Rheingold Playhouse” Durston could have hoped to confuse it with the more impressive Fairbanks series.

It’s very difficult to verify credits from Danger or the Kraft Television Theatre. Many of the segments are lost. Often the credits would be dropped if an episode ran long, or the reviewers for the trades or the newspapers simply wouldn’t catch them as they watched the show live. But the records for Studio One are closer to complete, and I’m convinced that I have seen an accurate list of writing credits for the entire run of Playhouse 90. David Durston’s name is not among them. Moreover, Playhouse 90 was a Rolls Royce of a show, very self-conscious about its prestige. With rare exceptions, only established “name” writers were invited to contribute to Playhouse 90, and Durston would not have fit that description.

Of course, it is possible that Durston contributed to one of these shows without credit – but all of them? I could go on: this book offers a Durston bio with still more credits that look bogus, including, of all things, Hart to Hart, whose writers have been well-documented and do not seem to include Durston. But you get the idea. Entertainment news does not, and never has, received the same scrutiny by editors and fact checkers as “real” news. Much of the information that gets accepted as fact is just plain wrong.

(And if anyone out there can provide any solid facts about the David Durston credits I’ve disputed, by all means post them below.)

Serge Krizman (1914-2008)

October 21, 2009

Production designer Serge Krizman died one year ago, on October 24, 2008, in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He was 94. Krizman’s death was reported at the time in his hometown paper, but has not yet been noted by any entertainment industry sources.

Krizman was the initial and/or primary art director on at least four important television shows: The Fugitive, Batman, Harry O, and The Paper Chase. He also designed sets for the Schlitz Playhouse, Happy Days, Charlie’s Angels, T. J. Hooker, and a number of other series and made-for-television movies.

Because of The Fugitive’s continued popularity, Krizman may be best remembered for his work on that series, which was realistic in its look and somewhat ahead of the curve in combining studio sets with extensive Southern California location work. (At the time, most TV dramas stuck to the backlot, if they went outdoors at all.) Krizman even attended at least one Fugitive fan convention in the nineties. But the most important item on his resume is unquestionably Batman. Very few television series can claim production design as the defining element of their creative makeup; Batman tops that list. Krizman’s designs drew on the DC comic, of course, but also expanded to include elements of exuberant camp and dry visual humor that were unique to the TV version. For that credit alone, Krizman merits a mention in the annals of television history.

That obituary in the Santa Fe New Mexican does a nice job of filling in some details of Krizman’s eventful life, but the author commits one serious error that I think is worth singling out. The obit lists a purported tally of the individual episodes of various series on which Krizman worked: 70 Batmans, 17 Fugitives, 13 Charlie’s Angels. I can guess where those stats were sourced. Wait for it: my old nemesis, the Internet Movie Database.

The problem is that the IMDb is still hit-or-miss in listing the episodic television credits of many people, especially “below the line” crew members. It will scoop up a few mentions on one series, and every credit on another, without much rhyme or reason. In that way, the database presents a very distorted portrait of the significance of specific shows within an individual’s career (or, conversely, the extent of a person’s involvement on a particular series). Just in the year since his obituary has published, the IMDb’s totals of Krizman’s Fugitives and Batmans have ticked upward by a few episodes.

I don’t have credit transcripts of any of those shows handy, so I can’t provide the correct numbers. But I can point out that, while Krizman was credited on all twenty-two episodes of Harry O’s first season, the IMDb records him as the art director for only two. The IMDb contains a lot of traps into which inexperienced users can fall, but that’s no excuse for journalists to depend on it for “facts” that cannot be confirmed from reliable sources.

Krizman in the early 1990s, at the Goldwyn Studio during one of the Fugitive fan reunions.