Shane

November 30, 2023

Like the following season’s Hondo, Shane (1966) is probably remembered, if at all, as one of those ill-conceived attempts to turn a movie classic into a television hit – a sheepish bit of intellectual property-mining that quite properly slunk off the airwaves after thirteen little-watched weeks. In fact, this unduly forgotten and mostly still unrediscovered series was one of the best Westerns to mosey along after the genre’s late-fifties television boom had turned to bust. It’s a smart, carefully made show, one with a distinctive visual style and stories that engage in substantive philosophical and political contemplation. Variety, in a tone that may or may not have been pejorative, characterized it as an “intellectual western.”

Shane was the first (and, as it turned out, only) series to emerge from a major realignment of the prominent independent producer Herbert Brodkin’s operations. After a long association with CBS that included Playhouse 90, The Defenders, and The Nurses, Brodkin’s agency, Ashley-Famous, had negotiated a liaison with ABC, still the ratings and carriage underdog among the big three. Meanwhile, Brodkin had sold Plautus Productions, owner of The Defenders and his other pre-1965 output, to Paramount, and had at least informally moved his operations under the film studio’s umbrella. It was a classic “what were they thinking?” acquisition, and the relationship would sour quickly, as Brodkin’s parsimony, contempt for hit-making, and general intractibility became apparent to his new corporate partner. But for a brief moment in 1965, the venerable movie studio saw Brodkin as the potential rainmaker it needed to catch up to MGM, Warner Bros., Fox, and Universal in the television market.

Just as Twentieth Century-Fox was doing concurrently (with The Long Hot Summer and Jesse James), and Warners (Casablanca; Cheyenne) and MGM (The Thin Man; Dr. Kildare) had done a decade earlier, Paramount that year initiated a “crash expansion” (Variety) of its television production by looking for entries in its back catalog of features that could be quickly adapted into ongoing series. Houdini, The Tin Star, and a Stirling Silliphant-scripted, serialized (in imitation of Peyton Place) reworking of Sunset Boulevard were all developed for television. (Who cared that a big-budget TV version of Paramount’s Oscar-winning The Greatest Show on Earth had flopped only a season ago?) Shane, the 1953 prestige western about a brooding gunslinger’s impact on the members of a young frontier family, was another obvious choice, and Paramount farmed it out to Brodkin’s new company, Titus Productions. In June 1965, Brodkin commissioned a pilot script from regular Nurses writer Leon Tokatyan.

Brodkin’s big debut of the 1966 season was supposed to be The Happeners, a topical look at the Greenwich Village arts scene that centered on a trio of folk musicians (vocalist Suzannah Jordan, plus Craig Smith and Chris Ducey, who later recorded as the Penny Arkade and retain a minor cult following among ’60s pop aficionados) and aped the flashy, disjointed look of Richard Lester’s Beatles movies. Instead ABC nixed the $400,000 pilot, citing advertiser disinterest, although I wonder if they were in fact spooked by NBC’s rival project The Monkees (or perhaps by Plautus’s last CBS series, Coronet Blue, a hard-to-describe adventure series that also feinted in a Mod direction, which so baffled the network that all 13 episodes were shelved for two years). ABC’s rejection of both The Happeners and another Brodkin pilot, the international-intrigue story One-Eyed Jacks Are Wild (with George Grizzard in dual roles as a Chicago gangster and a European prince), triggered a “one-for-three” contractual clause that forced the network to pick up Brodkin’s next pitch, no matter what it was. One imagines Brodkin forcing something even more esoteric into production out of spite, but, perhaps hoping to salvage the relationship or just in need of a hit, the producer went with Shane, which was commercially safer and likely cheaper than either of its more ambitious predecessors. Even placing a safe bet, Brodkin floated perversely uncommercial notions, like changing the title to keep the star in line (“If you named your lead character Shane, you can’t ever fire him. If you named it Western Streets, you can”). He lost that one. The pilot script was set aside (or it may have morphed into the episode “An Echo of Anger,” on which Tokatyan has a pseudonymous story credit) and Shane went straight into production.

The creative group in charge of Shane was an amalgam of Brodkin’s talent pool from New York (including half a dozen favored writers and directors he had used on The Defenders), plus a pair of Los Angeles-based young men with bona fide video oater experience: producer Denne Bart Petitclerc and story editor William Blinn. Both were recent Bonanza alumni. Petitclerc and Blinn reported up to David Shaw, who had evolved into the de facto showrunner of The Defenders at some point in the back half of the show’s run, after creator Reginald Rose scaled back his involvement due to exhaustion. Shaw – forever in the shadow of an older brother, Irwin, who after the war had become one of the country’s most prominent prose writers – had been a live TV playwright of moderate stature, associated with the Philco/Goodyear Playhouse during the period when its impresario, Fred Coe, was nurturing the likes of Paddy Chayefsky, Horton Foote, and Tad Mosel. Shaw’s work, though generally of high quality, had few of the overtly personal themes that made those writers’ reputations. Brodkin made him a partner in Titus Productions and Shaw leveraged the Shane job to pay for a move from the Big Apple’s dwindling prime time industry to Los Angeles, where he lived for the rest of his life.

(I met him there by chance one day in 2004 in the Century City Mall. I recognized Shaw’s second wife, the character actress Maxine Stuart, and followed them into a pharmacy, awkwardly introducing myself while they waited for their prescriptions. A nice man, Shaw later endured an interview, although he had long since shifted his creative focus from writing to painting, and seemed unencumbered by nostalgia for his television career. “Stupid idea,” he said of Shane. “I mean, Shane is a guy who travels around. You couldn’t have that [in a weekly series]. And we built a set. He was always about to leave and then he has to stay, every week.”)

Playing Shane was David Carradine, the oldest son of the eccentric character player John Carradine, but a prospective leading man due less to nepotism than to a recent, buzzy Broadway turn as an Inca god in The Royal Hunt of the Sun. In publicity for his new gig, a helpful Carradine disparaged the late Alan Ladd’s performance in the original Shane (“not really an actor at all but a personality” who “brought very little to the film”), and referred in another interview to Shane’s directors as “traffic cops” and its writers as “plotmongers.” He at least bonded with Petitclerc, a Hemingway acolyte and counterculture-adjacent figure who would later create the semi-autobiographical biker drama Then Came Bronson (which also starred a young actor with a talent for putting his foot in his mouth). Cocky or not, Carradine was the real deal, confident on camera and clearly a star in the making, but youthful in a way that contrasted with the world-weariness Ladd (ten years older in his Shane) brought to the character. Carradine cited Steve McQueen as a point of reference, and it’s easy to see McQueen’s opacity and reserve reflected in Carradine’s Shane.

The rest of the cast was hit-or-miss: the English ingenue Jill Ireland, too delicate to believe as a single mother toughing it out on the range, and beefy Bert Freed, an odd actor whose scowling boulder of a face was undercut by a soft voice and a diffident affect, as the villain Rufe Ryker. Freed was the guy you hired after Clifton James turned you down, although on the whole Shane succeeded at getting some Big Bad mileage out of his look alone. Folksy Tom Tully (who had enjoyed a recent career boost in Alan Ladd’s final feature, The Carpetbaggers) counterbalanced Freed as Tom Starett, Marian’s aged father-in-law.

Tully’s character is not in George Stevens’s Shane, and in the television series he takes the place of the character played in film by Van Heflin, the young husband/father. The movie’s most complex dynamic was the rivalry between Shane and Joe Starrett for the affections of Joe’s wife and son; while the boy’s hero worship of the outlaw is overt, Marian’s sexual attraction to Shane (and Shane’s own feelings for his friend’s wife) go largely unstated. The spectre of infidelity, suppressed in the film but perhaps less containable on a weekly basis, would’ve been a touchy subject for sixties television. Shane solved that problem neatly by making Marian a widow, its only significant change from the premise of the film. The other familial element that distinguished the feature – the tow-headed tyke whose point of view sometimes framed the depiction of violence and other adult motifs – remained intact, with the casting of a child actor (Chris Shea) who was virtually identical to the original’s Brandon de Wilde. Young Joey’s anguished cry of “come back, Shane,” from the indelible (and often lampooned) climax of the film, even makes an appearance in the third episode, “The Wild Geese.”

As David Shaw told me, the producers were preoccupied at the outset with making Shane’s clash between drovers and settlers sustainable. Shaw’s script for the first episode, then, reduces the film’s existential battle for the land to a skirmish, over the construction of a schoolhouse which comes to symbolize the permanence of the farmers’ community. This central conflict remains underdeveloped, but a side story in “The Distant Bell,” in which a schoolteacher (Diane Ladd) imported from the East realizes she has no stomach for frontier violence, begins to find the film’s sense of size and danger.

As its makers reprised some of the same topics they had broached in a quite different context in The Defenders, Shane affords a rare opportunity to examine what a leftist western looks like in practice. “Killer in the Valley,” in which plague comes to Crossroads, is a muted critique of capitalism that centers on a sleazy medicine drummer (Joseph Campanella) who exploits the tragedy for profit. Other episodes acknowledge the role of money in society in unexpected ways. In “The Wild Geese,” for instance, the bad guys turn upon one another after the rest of the gang learns that their leader (Don Gordon) is paying his newest recruit, Shane, more than them.

Ernest Kinoy’s “Poor Tom’s a-Cold” offers a progressive colloquy on mental illness, with Shane advocating talk therapy for a sodbuster (Robert Duvall) whose mind has been broken by the hardships of the frontier, while Ryker wants to put him down like a rabid dog. Shane compares Duvall’s character to a spider who keeps rebuilding a misshapen web, unaware that he can no longer conceive of how it should be spun, in the best of a series of compassionate monologues that Kinoy assigns to every character. Ellen M. Violett, the only woman who wrote for The Defenders, contributed a fascinating script about female desire, told from Marian’s point of view. The relatively weak lead performances (from Ireland and guest star Robert Brown) keep “The Other Image” from being the pantheon piece it might have been, but the ending, in which Shane and Marian work off their unspoken, pent-up sexual energy by chopping an entire winter’s worth of wood together, is brilliant.

Consistently, Shane discovered in its reluctant-hero protagonist opportunities to contemplate and often advocate for pacifism. Petitclerc’s “The Day the Wolf Laughed” is an outlaws-occupy-the-town story in which Shane offers a pragmatic, non-confrontational solution – the bandits entered Crossroads flush with loot and have promised not to plunder, so just wait them out – but Ryker’s boorish pride pushes the gunmen toward carnage. A more typical Western (like Gunsmoke, which did several variations on the town invasion premise) would usually invert these politics, casting the town’s craven merchant class as the appeasers while Matt Dillon or Festus maneuver to secure the advantage in a violent confrontation. Kinoy’s “The Great Invasion” depicts, with sympathy, a veteran so traumatized by the sound of gunfire that he won’t raise a hand to defend himself or others, and his “The Hant” subverts the catharsis of violence even more compellingly as it unveils a diabolical high-concept premise: an old man (John Qualen), the father of a gunslinger Shane shot down years earlier, turns up with a plan not to bury Shane in Boot Hill but to adopt the nonplused protagonist as a surrogate son to replace the one Shane killed. This was Blinn’s favorite episode, and decades later, in an interview in Jonathan Etter’s Gangway, Lord! The Here Come the Brides Book, Blinn enthused about a detail in Kinoy’s script that got somewhat lost in the execution: that Shane had killed so many men he couldn’t remember this one. “Day of the Hawk,” with James Whitmore as a preacher who embraces pacifism to stifle his dangerous, compulsive anger, is more skeptical, offering a cynical outcome in which the clergyman kills a semi-sympathetic character in cold blood in order to, perhaps, prevent an even greater tragedy. Here, too, though, the script (by Blinn and Barbara Torgan) gives Shane an unconventional point of view to articulate, a critique of organized religion as an ineffectual, self-indulgent response to the very tangible problems faced by settlers.

The best Shane episode is probably the sole two-parter (especially the first half), which has, among other things, Charles Grodin, in his first West Coast screen acting job, as a snotty New Yorker who gets his ass whupped (twice) by Carradine; Constance Ford as an extremely butch version of Calamity Jane who nevertheless has a Black male lover (Archie Moore, another veteran of Paramount’s The Carpetbaggers); and the Gatling gun as an explicit avatar of a technological escalation in frontier violence, three years pre-Wild Bunch. Again written by Ernest Kinoy, “The Great Invasion” anticipates the George Hearst storyline from Deadwood. Shane tries to make the homesteaders understand that the encroaching Eastern conglomerates pose a bigger threat to them than their accustomed antagonist, the small-potatoes cattle baron Ryker, but none of them can see the big picture, not even the Starett family. The Cheyenne moguls’ strategy involves hiring a mercenary (Bradford Dillman) to push the ranchers off the land on the flimsy pretext of hunting down outlaws. Kinoy’s target is not only predatory capitalism but also the fearmongering law-and-order politics that often enable it.

If that sounds dry or esoteric, it’s not, mainly because “The Great Invasion” is distinguished by one of the richest villains I’ve encountered in a television western. The conglomerate’s enforcer, General George G. Hackett, is a West Pointer who openly asserts that he is destined for military glory and an articulate gourmand who sneers at his employer for disdaining sweetbreads. He’s insufferable as well as psychotic, an unstable martinet who leads his men (arguably with some effectiveness) by inspiring fear rather than loyalty. Kinoy presents Hackett as at once formidable and pathetic, and Dillman, as good here as he ever was, grasps this contradiction and centers it as the essence of a dynamic and unexpected performance.

Am I going overboard in positing “The Great Invasion” as an allegory, conscious or unconscious, for the clash between Eastern (New York) and Western (Hollywood) sensibilities in Shane? Alongside the tropes I’ve detailed above, a countervailing and fairly compatible strand of sentiment runs through Shane, in scripts both syrupy (Ronald M. Cohen’s “The Silent Gift”) and satisfying (most of Blinn’s). The original Shane is about a frontier family, and it’s appropriate that some episodes should foreground this element (even after subtracting a key member of that family). The best of the domestic entries, “High Road to Viator” (at first titled, much more evocatively, “Blue Organdy”), concerns the theft, by scavenging Native Americans, of Marian’s prized party dress, and Shane’s efforts to recover it. Depicting in some detail the preparations for a three-day journey to another settlement to attend a party – Joey, we learn, has never heard of a piano – “Viator” runs high on warmth and atmosphere, and low on incident.

The family-oriented episodes, in particular, showcase this minimalist aspect of Shane, which seems to have motivated the show’s somewhat atypical formal strategies. Brodkin famously embraced the close-up as the building block of television mise-en-scene, and showed little curiosity about the vibrant New York world outside the courtroom and hospital settings of his CBS hits. Those precepts recur and flourish in Shane, a Western that plays out to an unusual degree in interior spaces, gorgeously amber-lit by director of photography Richard Batcheller (a longtime camera operator who had just matriculated to cinematographer gigs and died young, in 1970), and on the faces of the actors. “High Road to Viator” can plausibly be described as a “bottle show” (a deliberately under-budget effort to offset overages on other episodes), but so can several other Shanes, and the last one, “A Man’d Be Proud,” is a bottle show’s bottle show, a television hour as devoid of add-ons (no guest stars, no off-lot locations or new sets, no stunts) as it is possible to make.

If you ask whether these austere choices reflect profit motive or aesthetic preference, the answer is “yes” – the considerations are basically inseparable. (Compare Brodkin, perhaps, to Roger Corman and Russ Meyer, low-budget auteurs who were given big-studio toolkits and, on a fundamental, psychological level, couldn’t scale up to make full use of them.) A year after its cancelation, Variety snickered about how Titus Productions had pocketed a $30,000 per-episode profit on Shane, never mind the show’s conspicuous failure and presumed unsyndicatability. Blinn, in the Jonathan Etter interview, described a running battle between ABC, which wanted more action on screen, and Brodkin, who wanted them to pay extra for it; in the end, neither won. (Anecdotally, cutting corners to guarantee net income from the license fee seems to have been Brodkin’s business model during his Plautus days too, although I haven’t studied the balance sheets.) In The Defenders and The Nurses the professional settings compelled a claustrophobic feel, and a credible argument could be mounted that the scripts’ consciously didactic approach benefited from the absence of adornment or distraction. What’s remarkable about Shane is that, rather than showing up Brodkin as an indifferent cheapskate, it makes the same minimalism work just as well within a genre that typically opts for expansiveness.

It can be difficult, at a remove of decades, to assess a network and a studio’s commitment to a given project, but one reads between the lines and guesses that by the time it premiered in September 1966, Shane was a burnoff. Scheduled for the 7:30 slot on Saturday nights, it was predictably creamed by Jackie Gleason, although the third competitor – NBC’s Flipper – also trounced it, underlining the difficulty of marketing a western as wholesome family fare. (A few years later The Waltons and Little House on the Prairie would solve this riddle by keeping the period survival-struggle elements of the genre and ditching the rest.) By October the trades were already guessing at what would replace Shane on the midseason schedule, and in the end the show’s airdates were just tight enough to record the same year of birth and death in the history books.

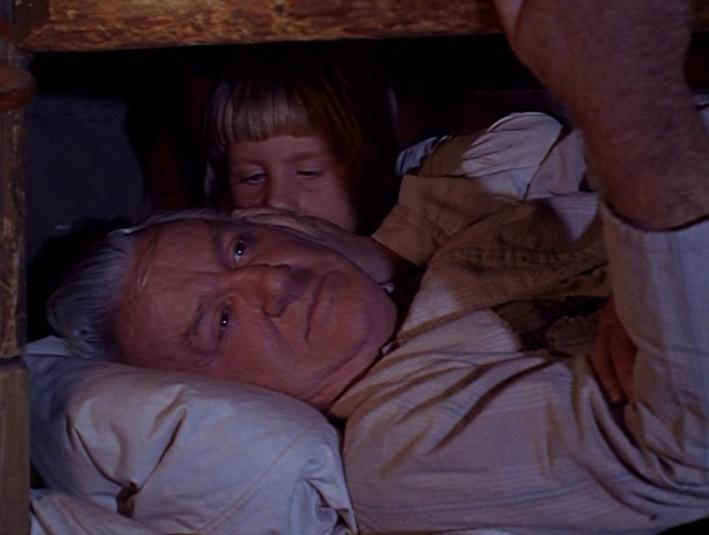

The few people still watching Shane on the last night of 1966 were greeted with that rarest of things in early episodic television: a resolution. The show’s instant lame-duck status gave Petitclerc and Blinn time to craft a finale that tied up the main characters’ storylines, perhaps only the second (after Route 66) in a prime-time dramatic series. After briefly considering Ryker as a serious romantic partner – not terribly plausible given all the mean things we’ve seen him do, but the writers have some devil’s-advocate fun making the stability he represents look tempting – Marian instead chooses Shane. Deliberately, I suspect, Petitclerc and Blinn invert the ending of the film, adopting their anti-hero into the community rather than casting him into the wilderness. This Shane does come back, or, rather, he opts not to leave at all. The series’ sweet last scene has an unnoticed Joey mouthing “wow” as he overhears Shane and Marian’s commitment to each other, then awakening his grandpa and whispering the news in the old man’s ear. It’s an unexpected shift away from the ostensible protagonists, and a fitting reprise of the subtle, off-center approach that defined this appealing little western.

Author’s note: Expanded and revised slightly in January 2024.

Crossing the Pond

April 25, 2017

A frequent and legitimate complaint about this blog has noted its author’s ignorance of British television, apart from a few oft-imported staples like The Prisoner and Are You Being Served? Be careful what you wish for: Here is a primer on four live and/or videotaped dramas of the sixties that remain largely unknown on my side of the Atlantic.

The Man in Room 17 (1965-1966) inverts the locked-room mystery in a clever way: it’s not the crime that occurs in the locked room, it’s the detection. It’s about two criminologists (why, one wonders, is the title of the series singular rather than plural?) whose skills are so rarefied and irreplaceable that they remain sequestered inside a chamber deep in the confines of the British government apparatus. On paper it sounds a bit like the American series Checkmate (1960-1962), which was created by a prominent British novelist, Eric Ambler, and had some vague pretensions toward emulating brainy literary whodunits. But Checkmate saddled its plummy British sleuth (Sebastian Cabot) with a pair of dullard underlings who spent most episodes getting conked on the head. The Man in Room 17 comes closer to fulfilling the rigor of its premise. Even when the crimes are routine, the dialogue is allusive and witty, and the intellectual vanity of the heroes is something no American series could conceive. Oldenshaw (Richard Vernon) and Dimmock (Michael Aldridge) – the first stuffy and acerbic, the other intense and arrogant – not only never get their hands dirty, they seem to revel in the cushiness of their surroundings. The two men evince no masculine vanity, no aspirations to physical courage. The only other regular character, portly, easily-flustered Sir Geoffrey (Willoughby Goddard), isn’t the bulldog one might expect, but an ineffectual liaison to the higher-ups in the government. He’s less of a boss than a glorified manservant.

Sir Geoffrey somewhat reluctantly takes a case to the supersleuths in the opening scene of the first episode, which is cannily designed to emphasize the secrecy and exclusivity surrounding Room 17. After that, the series largely avoids showing any of the bureaucratic tissue connecting Oldenshaw and Dimmock to the legal system. The show’s creator, Robin Chapman, isn’t interested in the mythology around Room 17 (which would be an irresistable temptation if the show were remade today), but in the limits imposed by the claustrophobic premise. Like the corpulent Nero Wolfe, these puppetmasters can’t operate without tentacles in the outside world. The easy way out would have been to assign them a regular legman, but instead the Room 17 gents recruit a different proxy for each operation – often through blackmail, trickery, or some other dubiously ethical machination. In one episode, their operative is discovered and killed by the bad guy. Dimmock and Oldenshaw react with shock and anger but not remorse. The episode “The Bequest” finds the fellows at their most mischievous and sinister. An American is advised to buy a chemical formula known to be fraudulent, and Room 17 finds this hilarious. Later Oldenshaw has the option to rescue an imprisoned operative but declines. “We always disavow our agents,” he shrugs.

The idea of the top-secret crimefighter’s lair isn’t unique – think of the Batcave, or the kid-lit characters the Three Investigators, whose hideaway is a mobile home deep inside a junkyard, accessible only by secret passage. Room 17 is an irresistable hangout, by stuffy bow-tied genius standards. There are no windows and one foreboding metal door, but also some comfy leather couches and a backgammon board. (The fellows play regularly, and backgammon pieces inspired the opening title graphics. I guess the idea was that chess was child’s play for these brainiacs.) A pleasure of visiting Room 17 today is trying to puzzle out how its occupants acquired and analyzed data back in the analog era. Somehow, via daily newspaper deliveries and just a handful of file cabinets and reference books (the prop budget was sparse, apparently), all the world’s knowledge is at their fingertips.

The bulk of The Man in Room 17’s cases involve espionage of one sort or another, which is probably a shame; it dates the show within a certain skein of Cold War paranoia, and attaches it as a sort of also-ran to the sixties spy craze. It offers an occasional frisson of the fanciful glamour of Bond, but lands closer to the grit of Le Carré. In the best of the first year’s segments, “Hello, Lazarus,” the men suspect that an industrialist has faked his own death in a plane crash, and set out to lure the fugitive into revealing himself. The script by Chapman and Gerald Wilson emphasizes the extent to which Room 17 operates without a mandate – Sir Geoffrey and his superiors do not share the men’s view that their quarry is still alive, and yet Oldenshaw and Dimmock brush that off and set to work anyway. The glee that Dimmock takes in manipulating the world bond market to solve a relatively inconsequential crime, and his not-terribly-sheepish concession that this represents a self-indulgent folly, are very funny. The writers permit the audience to consider that their protagonists may be ridiculous or even dangerous. Another standout 1965 entry, “The Seat of Power,” has a startling last-act twist, in which the men realize that the true target of an enemy’s up-to-that-point routine espionage operation is them: the whole scheme was designed as bait to flush them out of hiding, and it almost works. If the series were in color, you could see just how pale Dimmock and Oldenshaw turn when the caper suddenly acquires the life-or-death stakes that their isolation was designed to prevent. Though it is primarily procedural and apolitical, what is most intriguing about The Man in Room 17 is that Deep State subtext. It is, in the most literal way imaginable, about how the world is largely run by nondescript men in three-piece suits, invisible to most of us and subject to no one’s oversight.

*

Nominally a cop show, It’s Dark Outside (1964-1965) has grander ambitions. It stars character actor William Mervyn, a sort of tamped-down Robert Morley, as a posh, portly, utterly unflappable, and somewhat egocentric police inspector. In an American police drama, the seen-it-all cop tends to come across as a borderline psychopath who spends most of his off-screen time tuning up suspects with the butt of his pistol: Joe Friday or Vic Mackey. Mervyn’s character, Detective Chief Inspector Rose, has the opposite sort of authority, the kind that suggests he can tie a neat cravat but likely has never deigned to pick up a firearm. Rose, with his perilously rounded R’s, seems to have wandered in from an Agatha Christie novel, but the world he polices is the modern one, awash in sexual perversion, racial violence, and other sordid, straight-from-the-headlines social ills. The gimmick of It’s Dark Outside is that it mixes traditional crime elements with aspects of other genres in a pretty explicit bid to declare itself as a serious drama. The show’s story editor, Marc Brandel, was a rare transatlantic television scribe, who had put in time on American shows like Playhouse 90 and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour; it’s tempting to speculate that he had been exposed to liberal dramas like East Side / West Side and especially Naked City, and took a bit of inspiration from them for It’s Dark Outside.

The supporting cast of It’s Dark Outside steers the show outside the squadroom. Rose’s stuffy, upper-crust old friend Anthony Brand (John Carson) is a top executive in a human rights organization. His work triggers a running dialogue of liberal social theory versus the implicitly conservative law-and-order stance of the police (although DCI Rose is more of a hard-headed pragmatist than a right-wing ideologue, so the debate is more proscribed than in any comparable American work). Unlike the seemingly celibate Rose, Brand is married, to a smart, sophisticated beauty who chafes at the do-nothing activities her sex and social position force upon her. Just why a cop show should take an interest in these society types isn’t clear at the outset, but the show’s unexpected and ultimately very rewarding focus on Alice Brand (June Tobin) turns It’s Dark Outside into a stealth domestic melodrama.

The fourth regular character is the inspector’s apprentice, a brash young cop in whom Rose insists on seeing promise despite all evidence to the contrary. Rose actually goes through two of these: Sgt. John Swift (Keith Barron), a novice whose carelessness gets a suspect killed in the first episode, and later Sgt. Hunter (Anthony Ainley), who barely conceals his contempt for a boss he thinks of as a pompous old duffer. Brandel may be seeking to upend the traditional mentor-mentee relationship, although I can’t make out quite what It’s Dark Outside is trying to do with it, particularly in the case of the insubordinate Sgt. Hunter, since most of his episodes are now lost. I tend to view Rose’s confidence that he can mold these unyielding lumps of clay into top-shelf sleuths as evidence that his solipsism has a down side.

In any case, Sgt. Swift has a more important purpose than teasing out the shadings of Mervyn’s character. The secret heart of It’s Dark Outside is the flirtation that develops between Swift and Alice Brand – a smoldering May/July attraction that had to have been one of the most erotic relationships on British television in the sixties. During the initial episodes, it’s not even clear that this element is intentional – is Brandel playing a long game, or are the actors just getting creative with subtext? Often in sixties television this sort of running character element came with no guarantee of a payoff, but It’s Dark Outside turns out to have been a proto-miniseries. The last three episodes of its initial arc are explicitly serialized, and the penultimate one, “A Case of Identification,” brings the Swift-Alice storyline to a complex and satisfying conclusion. When they drift into a mostly guiltless affair, the dynamic between Swift and Alice Brand turns on their age difference. Alice likes the cop because she thinks he’s “weak”; he replies, “I don’t want to be mothered.” The older woman has the power in the relationship, but the writing doesn’t caricature her as either pathetic or predatory. Alice is sexually assertive and sympathetic; Sgt. Swift never counters with an assertion of machismo; and neither expresses any remorse at having flouted Alice’s marital bond. It’s a more truthful and less judgmental sketch of an extramarital dalliance than American television could have undertaken for another decade or more. Another serial thread runs parallel to that one – a blackmail storyline involving Anthony Brand – and while it’s less involving overall, it sets the stage for a shocker ending to the 1964 cycle. Genteel on the surface, It’s Dark Outside proved capable of dispatching secondary characters as ruthlessly as 24.

*

The fascinating The Plane Makers (1963-65) is one of the few television shows to make a full transition from (themed) anthology to standalone drama to serial. In its first year it told one-off stories with a shared setting, the vast airplane factory Scott Furlong; in its second it tightened its focus to a common set of characters; in its third it placed the most charismatic of them at the center of a thirteen-episode continuity. Like some of the Camelot-era shows in the United States – Dr. Kildare or Empire or even The Dick Van Dyke Show – The Plane Makers cultivates a sleek, technophilic optimism. Instead of the characters, the opening titles show a jumbo jet crossing a taxiway and entering a hangar – lumbering rather unsexily, as it happens, but the soaring music gets across the idea that this show is about the movers and shakers who are busy creating our George Jetson future. However banal the lives of some of these salarymen might prove to be, the notion that prosperity is the key to a modern world of ever-expanding possibilities surrounds them. It’s no surprise that The Plane Makers founders on the same class disparities that Peyton Place, which is the closest American analogue I can come up with, struggled to encompass. In its second year, the show tried a split-lead approach, with two main characters starring in alternating segments and rarely sharing the screen. Patrick Wymark plays John Wilder, the company’s corporate managing director, a charismatic bulldog who’s good enough at his job that he gets away with being a complete asshole. His counterpart is Arthur Sugden (Reginald Marsh), a middle manager who runs the factory and takes a soft-spoken, staid approach to solving problems. Sugden smokes a pipe, while Wilder chain-smokes cigarettes – just one of many details that carefully delineate these characters as moral and temperamental opposites. (Wilder is a Londoner and Sugden from Yorkshire, a sort of city-versus-country mouse cultural distinction, although the subtleties are lost on this American.) Sugden’s patience and reserve, his allegiance with blue-collar labor, his quaintly old-fashioned way of dressing and carrying himself all designate him as the show’s conscience.

The problem, of course, is that Sugden is incredibly dull – almost perversely so, as if Wilfred Greatorex, the show’s creator, wanted to make the point that the best men among us are often the milquetoasts and mediators who don’t get any credit or attention. Good luck turning that into compelling conflicts every week, especially when a raging monster like John Wilder is on the other end of the seesaw. The clash between the two men arises in the second segment (“No Man’s Land”), in which Sugden squares off against Wilder over management’s scapegoating of a lowly workman for the failure of an expensive test flight. Wilder’s quest to push his new plane, the Sovereign, to completion provides the backdrop for this second cycle, occasionally boiling over into open showdowns with Sugden or other supporting characters (Barbara Murray plays Wilder’s poised wife, Jack Watling his fidgety yes man, and Robert Urquhart a stolid test pilot).

The Plane Makers strives to contemplate capital and labor with the measured, cerebral approach of the editorial page. “Don’t Worry About Me,” the series’ premiere (and the only anthological episode that survives; as Doctor Who enthusiasts well know, many videotaped British dramas of the sixties and early seventies were recorded over, a fate that annihilated early Tonight Shows and daytime soaps but spared most scripted American prime time shows), addresses a cross-section of professional concerns surrounding a skilled but overbearing metalworker (Colin Blakely) with a casual attitude toward safety and a promising apprentice (Ronald Lacey) given the choice of leaving the shop floor for a less lucrative but more upwardly mobile office job. Writer Edmund Ward emphasizes the resentment that both men express toward their superiors, which seems to conceal a more existential dismay as to how little control either man has over his future. As they play out, the stakes for Blakely’s and Lacey’s characters are lower than they sound on paper – a momentous career decision for a young lad is so inconsequential to the bosses that they have to be reminded about it every time it comes up. The melodrama in The Plane Makers is consistently pitched at a lower level than in any similar American project. Devastating verdicts on a man’s prospects or character are delivered in offhand remarks: at the end of “No Man’s Land” Sugden prevails, and is granted a contested promotion, but a board member adds that there is “no particular confidence in you or your ability.” That’s a line that drops like a hammer if you’re in tune with Greatorex’s show. I always roll my eyes at the idea of “slow cinema,” or critics who condescend by urging allowances for it, but The Plane Makers does reward the American viewer who recalls the old cliches about British reserve and pays attention to all the unspoken or primly articulated nuances that pass between the characters – except of course for John Wilder, the show’s id, who must have been refreshingly easy to write for. Contemporary reviews of The Plane Makers fawn over Wymark’s performance and the dynamism of his character, which proved so obviously the breakout element of the show that some of its subtler elements had to give way.

Although Wilder’s anti-hero charisma is undeniable, the best Plane Makers episodes are vignettes that describe the impact of progress on the Scott Furlong rank and file. Factory stalwarts get crushed in the unforgiving maw of rampant capitalism; executive suite schemers self-destruct when they imitate Wilder’s ambition but lack his guile. “A Question of Sources” concerns a sleazy security chief (Ewan Roberts) on a witch-hunt for the source of a leak. “All Part of the Job” dissects an unscrupulous climber (Stanley Meadows) who sets out to dispose of a rival – a decent, competent purchasing executive (Noel Johnson) – after he discovers the older man has taken bribes from a vendor. The first episode has a spy-movie suspense driving the story, while the second feels like Mad Men without a historical frame drawn around it. And while The Plane Makers is unabashedly about the men in the grey flannel suits, it makes time to sketch sophisticated, sympathetic portraits of the Joans and Peggys in its world. “A Condition of Sale” explores how a seasoned secretary (UFO’s impressive Norma Ronald, a semi-regular) fends off scuzzy sales reps, and contrasts her efficient, blasé rebuff of a crude pass favorably with Sugden’s chivalrous but counter-productive bluster when he learns of the offense. In “Sauce For the Goose,” the long-suffering Mrs. Wilder contemplates an affair with a solicitous American; in a hint at the limits of The Plane Makers’ perspective, it’s less successful than the earlier “A Matter of Priorities,” which chronicled the sordid details of Wilder’s own extramarital indiscretion.

*

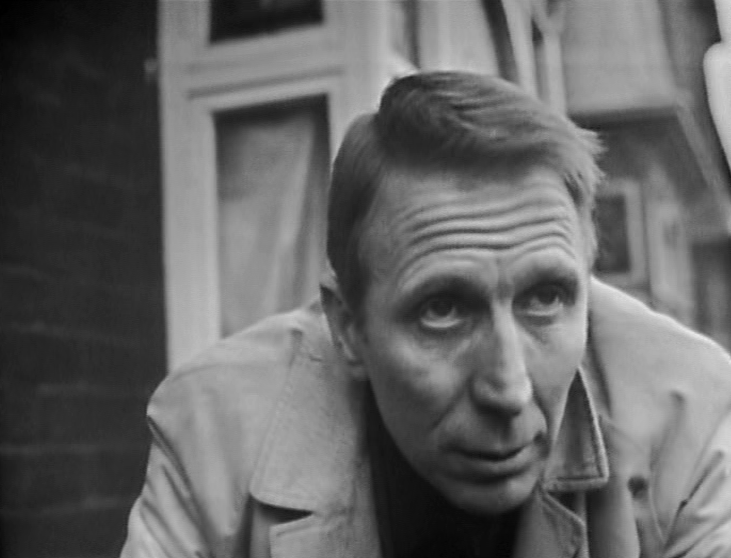

Public Eye (1965-1975), the best-known and most beloved of the four shows I’m looking at here, centers upon a seedy, modestly-appointed “enquiry agent,” a lean, taciturn chap named Frank Marker. It has the feel of a rain-slicked jazz noir, like Hollywood’s Peter Gunn or Richard Diamond, Private Detective, but it’s even more downbeat – at times Public Eye is almost as terse as a Parker novel. (It’s a literal jazz noir, by the way: Robert Earley’s theme song is one of the greats.) Like Jim Rockford, Marker comes off as a loser on the surface, a fringe figure in an absurdly cramped rooftop office who skirts the law because it’s the only way he can make a living. At the same time he’s dogged and has a moral code and, when it really counts, he can kick ass. Marker even has a bit of style: most of the time he wears a light-colored tie over a dark shirt and coat, like a reversal image. It was a career-making role for the great Alfred Burke, a small-part movie actor whose hangdog face adds layers of dignity and pathos to the literate dialogue.

The mobster’s beating Marker takes in the early episode “Nobody Kills Santa Claus” is startling because violence happens so rarely in Public Eye. Marker’s job is tedious and grubby – a world away from Joe Mannix’s weekly gunshot wound to the shoulder. Written largely by its versatile co-creator Roger Marshall, who was barely out of his twenties at the start of it, Public Eye could encompass milieus both seedy and urbane. “The Morning Wasn’t So Hot” is a frank depiction of the prostitution racket, filled with vivid little portraits of feral pimps and the callow young women who flourish in the trade. It climaxes in an amazingly blunt, poetic exchange between Marker and the hard-bitten girl he’s been searching for, who is too far gone to return to the straight life. The divorce case “Don’t Forget You’re Mine” introduces a missing husband (Roy Dotrice) who quotes T. S. Eliot and a kooky mod girl (Diana Beevers) for Marker to flirt with; it also has one of the cleverest midpoint reversals I’ve seen in a private eye story, one with devastating emotional consequences. A courier for strangers’ miseries, Marker takes cases that limn the seedy underside of human nature – his work isn’t so much solving mysteries as handling, by proxy, the personal interactions that his clients can’t bear to endure themselves. “The Bromsgrove Venus,” my favorite early episode, is sad, funny, and absurd. It’s about a petty blackmail scheme over a tame nudie pic (so tame we even see it on-screen!), which succeeds only because the repressed, middle-class husband and wife it targets won’t talk to each other at all.

Public Eye doesn’t transcend genre – it doesn’t try to pretend it’s more than a private eye show – but like all great crime stories it’s expert at using the conventions of genre to explore all the heartbreaking ways in which humans do harm to one another. The seven episodes made in 1969 comprise a contemplative serialized arc, in which Marker, having done a stint in prison for corruption, is released on parole in an unfamiliar coastal town. “Welcome to Brighton,” the premiere, is the story of a man coming slowly and humbly back to life. No longer licensed as an investigator, Marker works as a laborer, breaking rocks on the beach to build a retaining wall. This is an optimistic depiction of prison, of a piece with the U.S.’s Great Society television dramas. Marker’s parole officer is sympathetic, his support system works, and the implication is that Marker may not be just rehabilitated but rejuvenated by incarceration and its aftermath. The off-the-books cases in this septet are trifling (a stolen pay envelope) or intimate (a young woman’s suicide attempt). The emphasis is unequivocally on the personal, especially Marker’s tentative romance with his new landlady (Pauline Delany). The arc’s final episode has no detecting at all, only relationship counseling, as the landlady’s estranged husband returns and Marker must gently dissuade him from making trouble. All seven of the 1969 episodes were written by Marshall, who, after four years, must have decided he wanted to get to know his creation better: without a professional life to fall back on, Frank Marker, depicted in his earlier adventures as little more than a sponge for his clients’ negative energy, has no choice but to try to become a whole person.

The last Public Eye of the sixties is also the first that exists in color. Watching it is a bit like last call in a dark, smoke-filled pub, when the bartender flips on the lights to urge everyone home: the atmosphere instantly vanishes. Finally we learn the true color scheme of Marker’s trademark tie and shirt (spoiler: light purple on dark blue), but it feels like a poor trade. Public Eye would continue, mostly in color, until 1975. Like Marker himself, it was incapable of stasis; during its eleven-year span, under the auspices of two different production companies, the peripatetic show shifted production from London to Birmingham to Brighton to Windsor to Surrey. Despite its limited capacity for exterior filming, Public Eye captured a fair amount of regional color in each setting.

*

Americans often remark, either with contempt or relief, on the smaller size of the typical British TV run – never mind that The Plane Makers toted up a whopping 28 hours during the year it groomed Patrick Wymark as its star. Equally notable was its creators’ and sponsors’ capacity for metamorphosis. One thing I set aside in describing the shows above is how each represents a snapshot in a fairly complex continuity. The Plane Makers not only changed formats three times during its three-year run, it also morphed into a sequel series – called The Power Game (1966-1969) – that followed John Wilder into a new job. The Man in Room 17 shed a cast member (Denholm Elliott replaced Michael Aldredge) and then, when Aldredge returned, adopted a change of setting and a new title, The Fellows (1967). The Fellows in turn launched a spinoff mini-series from creator Robin Chapman, Spindoe (1968), which itself spawned a follow-up, Big Breadwinner Hog (1969), that was narratively unrelated but originally intended as a direct sequel. It’s Dark Outside was the second of three shows, each from a different creator/producer, that featured William Mervyn as the same character. I haven’t seen the first, The Odd Man (1960-63), which survives but isn’t commercially available; the third, though, is wholly different in tone and structure from its predecessor. Sending DCI Rose off into suburban retirement, Phillip Mackie’s Mr. Rose (1967-1968) is erudite but bloodless, a Masterpiece Theatre-ish concept with less distinction than It’s Dark Outside. The best thing about Mr. Rose is the running gag of how the ex-cop keeps stumbling upon, and solving, crimes because doing so is easier and more appealing than his stated purpose of penning his memoirs. As a so-called writer who has published only one other piece in the last nine months, I wish I could report that I’d nabbed the Zodiac during the hiatus.

Just as U.S. television encouraged maximalism – when Peyton Place breaks out, put it on three times a week! – it also shunned any tinkering with a winning format. The only series that were given makeovers were those that flailed in the ratings. For Bonanza or The Beverly Hillbillies, sameness was the only option, no matter how tedious the formula might get – and of course Nielsen existed to endorse that kind of conservatism. If viewers ever abandoned a show because they wanted to see its characters change and its stories evolve, that was a subtlety Nielsen couldn’t measure. What was it about the British that allowed for portion control, and made them able to bid farewell to a popular entertainment before it wore out its welcome?

Stephen’s adventures in transatlantic television may or may not continue later this year with a look at more ’60s British program(me)s, thanks to Network, BFI, and few other UK labels that have released a bounty of hard-to-see shows on DVD or Blu-ray during the past few years.

Defending the Defenders

July 14, 2016

The Defenders is one of the most important television series to air on an American broadcast network. It won more than a dozen Emmys, including three consecutive trophies for best drama (a record not broken for another two decades, by Hill Street Blues). At a moment when the dramatic anthology was on its deathbed, and ongoing series were often (fairly or not) thought of as meritless escapism (Newton Minow’s “vast wasteland” speech depends on this context), The Defenders created the template for what we now think of as quality television. It was a show with both feet in the real world: where other smart dramas gave their elements of social commentary some shelter within genre (Naked City; The Twilight Zone), melodrama (Peyton Place), or abstraction (Route 66), The Defenders was bluntly political. Its basic premise – Lawrence Preston (E. G. Marshall) and his son Kenneth (Robert Reed) run a small Manhattan law firm with an appetite for controversial cases other attorneys might avoid – was in the most literal sense a formula for debating hot-button issues in the guise of fiction. While similar shows have often worn a fig leaf of balance, The Defenders trafficked in advocacy, taking liberal or even radical stances and articulating counterarguments mainly so that it could knock them down. It was pro-abortion and anti-death penalty, anti-nuke and even pro-LSD. Although it lasted for four years in part as CBS’s highbrow show pony (and self-important network chairman William Paley’s unstated apologia for the likes of The Beverly Hillbillies and Gilligan’s Island), The Defenders was at least a modest hit, cracking the Nielsen top twenty during its second season. It became the key precedent for shows like The Senator and Lou Grant and a name-checked inspiration for some of the present century’s smartest dramas, including Boston Legal and Mad Men. Had this bold series failed to achieve both popular and critical acclaim, and done so without compromising the elements that made it noteworthy, prime time probably would have been a lot dumber in the decades that followed.

Unfortunately, The Defenders has fallen into apocalyptic obscurity during the fifty-one years since it went off the air. Though it did have a short life in syndication (which is still more than its Plautus Productions siblings, including the excellent three-season medical drama The Nurses and the cult whatsit Coronet Blue, enjoyed), The Defenders had largely disappeared from view by the time VCRs made it possible for collectors to capture and circulate any obscure show that turned up in reruns somewhere. The last known sighting, a short run on the Armed Forces Network circa 1980, is the source of a few of the thirty or so episodes (out of 132) that have found their way into private hands (and eventually onto YouTube). Cerebral shows and black-and-white shows are a hard sell, to be sure, but The Defenders was further hampered commercially by split ownership (between CBS, the corporate successor to its executive producer Herbert Brodkin, and the estate of its creator, Reginald Rose) and possibly by talent deals that established complex, non-standard residual payments. Although short-lived shows often vanish into the studio vaults, it’s extremely unusual for any series that crossed the 100-episode syndication barrier – much less one that took home thirteen Emmys – to remain so thoroughly unseen for more than a generation. That’s why this week’s DVD release of the first season of The Defenders can legitimately be described, at least within the realm of television, as the home video event of the century.

Me being me, I’d like to briefly discuss why this might not be an altogether good thing.

Remember how The Andy Griffith Show spent part of its first season with Andy as a gibbering hillbilly, before Griffith figured out that he was the straight man? Or how M*A*S*H uneasily aped the chaos of Robert Altman’s film before focusing on its core characters, or how Leslie Knope was an idiot at the beginning of Parks and Recreation? First season shakedown cruises are almost a tradition among great sitcoms, but long-running dramas sometimes take them, too. Mannix started with a convoluted, allegorical format and struggled until its second-season reversion to classicism; Kojak needed a year to get off the backlot and flourish in full-on French Connection, Beame-era Big Apple scuzziness. The Good Wife (another recent show with a lot of Defenders DNA in it) and Person of Interest each slogged through half a year of dull standalone stories before committing to bigger, more original narrative arcs.

You probably see where I’m going with this: The Defenders is one of those shows that didn’t hit its stride until its second season. Although there are many strong hours in the first year, and I’m going to enthuse about some of them in a moment, nearly all of the series’ worst duds can be found in this initial DVD set, too.

The Defenders has often been characterized as the anti-Perry Mason. If Mason was an unabashed fantasy of the defense attorney as an infallible white knight, The Defenders was a corrective that depicted the law with an emphasis on realism and moral ambiguity – to the extent of permitting the Prestons to be among the few TV lawyers, then or now, to lose their cases. Reginald Rose’s lawyer, Jerome Leitner, was credited as a consultant on The Defenders, and one suspects that his influence was considerable. As it evolved, The Defenders’ interest in the arcana of legal procedure came to define it. (Long before The Good Wife made it a seasonal tradition, for instance, The Defenders liked to drop its lawyer heroes into non-standard courtrooms and show them struggling to master their procedural quirks. The first season’s “The Point Shaver” takes place in a Senate hearing, and “The Empty Chute” in a military tribunal.)

It’s a shock and a reality-check, then, to find Lawrence and Ken Preston engaging in some very Perry Mason-esque courtroom theatrics in the early episodes, even to the extent (in “The Trial of Jenny Scott” and “Storm at Birch Glen,” among others) of badgering confessions out of the real culprits on the witness stand. Moments like these are a bit of an embarrassment compared to the more serious-minded tone The Defenders would soon adopt; in hindsight, they seem like something from a different series altogether. In general, the first year was overreliant on personal melodrama rather than legal procedure as the basis of stories. “The Accident,” for instance, was the first episode whose climax turned on an obscure point of law; it was the eighth to air. “The Broken Barrelhead,” the first season finale, posits an intriguing ethical dilemma that’s been revived lately in news coverage of self-driving cars: was a driver right to plow into a group of pedestrians in order to save the passengers in his car? But David Karp’s teleplay sidesteps the trolley-problem debate to focus on the very conventional conflict between the callow defendant (Richard Jordan) and his blowhard father (Harold J. Stone).

Were Rose and company, or the executives at CBS, worried that too much legalese would alienate the audience? I’m speculating here because I still don’t really understand why season one of The Defenders is so frustratingly all over the map. The archival record may answer the question definitely (Rose’s and several of the key writers’ papers are at UW-Madison, Brodkin’s at Yale), but I haven’t had the chance to explore much of it; and while I’ve interviewed many people who worked on The Defenders, all of them remembered its glory days with far more clarity than its early missteps. Network interference is an obvious possibility: when I spoke to CBS executive Michael Dann in 2008, he called the famous “The Benefactor” episode “a turning point,” implying that The Defenders didn’t have a firm mandate to get political until it tackled abortion head-on and got away with it. The eighteenth episode, “The Search,” has a prosecutor (Jack Klugman) and an implausibly naive Lawrence Preston doing a post-mortem on an old trial after they learn that Preston’s client was sent to the electric chair for a murder he didn’t commit. The structure of Reginald Rose’s script is misshapen and the ending is a cop-out, and I’ve always suspected “The Search” was a neutered attempt at the kind of death penalty broadside that would become The Defenders’ signature issue – addressed passionately in “The Voices of Death,” glancingly in the bravura two-parter “Madman,” and definitively in the astounding “Metamorphosis,” all from the second season. The network continued to wring its hands throughout the run of the series, shelving an episode about cannibalism (!) for a year and authorizing the classic “Blacklist” only after the producers agreed to drop a race-themed script in exchange. The difference in these later clashes was just that once the Emmys started to pile up, the producers had more leverage.

Along with the degree of network tinkering, the major unknown in understanding the early content of The Defenders is the extent and nature of Reginald Rose’s contribution. The Defenders was unquestionably Rose’s show, although it’s revealing that throughout the series’ run he received screen credit only as its creator, never as a producer or story editor. Rose was extremely hands-on at the outset, to the extent that TV Guide reported on murmurs from disgruntled freelance writers who deployed pseudonyms to protest Rose’s copious rewrites. Overwork triggered some sort of physical breakdown late in the second season, which required Rose to reduce but never wholly end his involvement in the writing. (From 1963 on, it’s likely that David Shaw, credited as a story or script consultant, was the de facto showrunner.) But Rose penned only a dozen original teleplays for The Defenders, a startlingly small number compared to the totals racked up by Rod Serling on The Twilight Zone and Stirling Silliphant on Route 66. A few of those 12 are masterpieces, and the last of them (“Star-Spangled Ghetto”) plays as a kind of belated mission statement for the what the show wanted to be about; but more of them feel compromised or desperate, as if Rose was bashing out flop-sweat scripts to fill holes in the production schedule. The second season’s “Poltergeist,” an eccentric bottle show in which the Prestons solve a locked-room murder in an isolated beach house, has elements of concealed autobiography (it takes place on Fire Island, where Rose vacationed in those days) and almost seems to be a cry for help, a subconscious acknowledgment that Rose would rather have spent the winter of 1963 doing anything but writing The Defenders.

I point all of that out in order to advance a hesitant case that in his approach and his skill set Rose may have been less of a Serling or Silliphant and more like, say, Gene Roddenberry on Star Trek. Roddenberry had a strong, compelling overall vision for his creation, but proved to be a less talented episodic writer than Gene L. Coon, D. C. Fontana, and some others on the show’s staff. It’s hard to point to anything of prodigious quality in Roddenberry’s dialogue or even his prose, and yet every subsequent variation of Star Trek has abandoned the philosophical and structural underpinnings that Roddenberry laid down in the original series at its peril.

In Rose’s case, there’s a thematically coherent body of Studio One scripts that establish his preoccupations with ethics and rhetoric, culminating with 12 Angry Men, his declaration of interest in the intersection of jurisprudence and liberal values, and “The Defender,” a live 1957 two-parter that served as a blueprint for the subsequent series. “The Defender,” with Ralph Bellamy and William Shatner as the Prestons and Steve McQueen as the defendant, is pretty clunky, and it’s noteworthy that when Rose reworked the script as the series’ pilot, “Death Across the Counter,” he improved it. (The third episode broadcast, “Death Across the Counter” was shot in Los Angeles more than a year before production began – an atypically long delay, during which the show was all but brought back from the dead in spite of sponsorial indifference – thus adding to the first-season sense of The Defenders being a different show every week.) The crude generational conflicts between the Prestons in “The Defender” are reshaped into more specific clashes over legal strategy and philosophy in “Death Across the Counter,” and this explicit refinement of a theme over time makes me think that Rose, as The Defenders went into production, was still actively working out what he wanted to say and how best to say it. Mining drama from the statutes is one of those conceptually pure ideas that looks obvious in retrospect, but maybe Rose had to chisel away the hysterics of a thousand hacky courtroom dramas to see it. 12 Angry Men, Rose’s best work prior to The Defenders, emphasizes archetypes over specificity – in a way that’s conscious and effective (especially in the film version, where Henry Fonda’s persona of common-man rectitude provides a lot of symbolic gravitas), but is often seen as reductive, self-important, or dated in modern critiques of the piece. (See Inside Amy Schumer’s dead-on parody.) As Serling and Silliphant poured forth with high-flown philosophy and idiosyncratic syntax that always felt fully formed and absent of self-doubt, Rose may have been more process-oriented, messier, and by nature chameleonic. Did all those pseudonymous writers complain because the best elements of their episodes were the refinements that Rose added?

Launching an innovative series is always burdened with a prosaic risk – can you find enough people who will understand how to write it? And Rose, lacking the Serlingian-Silliphantian stamina to pen the lion’s share himself, was at a perilous disadvantage. The first season’s credits are full of one- or two-off writers who weren’t asked back. There are other flaws at work, too, including skimpy production value (something that never really changed; The Defenders was an interior-driven show, and any expectations of further exploring the vintage New York of Naked City must be gently managed), tonal inconsistencies (check out the weirdly overemphatic presentation of the Prestons’ old-school-ties nostalgia at the beginning of “The Point Shaver”), and direction that’s a bit stodgy. Herbert Brodkin’s aesthetic was notably conservative – he favored endless extreme closeups to the extent that his directors referred to this set-up, contemptuously, as a “Brodkin.” (Not to mention that most episodes climaxed in the confines of a courtoom – a setting where convention placed severe constraints on any potential flourishes in set design or composition. Did any of the great directors do their best work filming trials?) The Defenders eventually came to have some of the forceful compositions and contrasty, documentary-styled lighting that one finds in the New York indie films of the day. The series’ most visually imaginative director was Stuart Rosenberg (Cool Hand Luke), who debuted with a late first-season episode and became a regular the following year. Aesthetics, too, were a work in progress.

For skeptics, the best way to tackle The Defenders on DVD might be to skip ahead to “The Attack,” the thirteenth episode broadcast and the first one that is unquestionably great. Featuring Richard Kiley as a surly beat cop whose daughter is sexually assaulted, “The Attack” tackles both pedophilia and vigilantism. The outcome of the trial ends up feeling anticlimactic; what’s notable about the ending of “The Attack” is that Lawrence Preston has grown disgusted with his client, has come to believe in the man’s moral guilt. Think about that for a moment: The Defenders positions Preston as its putative hero, yet here it shows him rejecting the kind of eye-for-an-eye emotionalism that was axiomatic in westerns and crime dramas, in a way that dares the audience to consider him unmanly. In what would become another recurring theme of the series, “The Attack” advocates for the necessity of institutional over individual justice; the catharsis of the latter is depicted as a refuge of barbarians. This was almost beyond the pale at a time (and, really, this is still the case today) when television’s vigilantes were often sketched sympathetically even as, say, a reluctant Matt Dillon punished them, and when masculine honor and physical courage were (or are) unassailable. Route 66’s Tod and Buz might’ve been wandering poet-bards of the asphalt frontier, but they still managed the beat the shit out of some unhip lunkhead (or each other, if lunkheads were in short supply) most weeks. Preston prioritizes his ethical obligations over his personal feelings, and does so without a great deal of hand-wringing or soul-searching. He’s a professional; this is simply how the law works. Other smart, liberal Camelot-era dramas would play on this conflict between duty and personal conviction, but in ways that flattered the hero and the audience. When Ben Casey solemnly invoked the Hippocratic oath and performed life-saving surgery on some maniac who murdered three people before the opening credits, it ennobled him; when the Prestons used legal trickery to get some mobster or neo-nazi off on a technicality, it was an inescapably sordid affair. Moral victories could also be Pyrrhic ones.

All of this strikes me as a huge advance beyond even 12 Angry Men, with its unthreatening man-against-the-mob calculus, and other high water marks of live anthology drama. The Defenders insisted that the audience respond to the material intellectually as well as emotionally, and it confounded traditional, unquestioning identification with a show’s protagonists to a greater extent than anything else on television prior the antihero cycle of The Sopranos, The Shield, Mad Men, et cetera, forty years later.

After “The Attack,” episodes that are just as complex and confrontational start to alternate with the clumsy ones. “The Iron Man” is a profile of a young neo-nazi (Ben Piazza) that wades into the paradoxical weeds of free speech absolutism. “The Hickory Indian” draws a moral parallel between the mob and prosecutors who use strongarm tactics to pressure an informer into testifying against it. “The Best Defense” features Martin Balsam as a matter-of-fact career criminal railroaded on a bogus murder charge; the Prestons agree to defend him on the grounds that crooks deserve good legal representation as much as anybody else, and they’re rewarded for their idealism when Balsam’s character, scorpion-and-the-frog-style, implicates them in a false alibi. “The Locked Room” uses a Rashomon structure to chronicle a “Scotch verdict” case, in which the prosecution can’t prove guilt but the defense can’t mount a persuasive case for innocence, either. Its themes are existential: lawyers often don’t know or even need to know whether their clients are guilty; trials often fail to get anywhere close to the actual truths of a crime.

I suspect that “The Locked Room” – the title refers to the jury’s place of deliberation – was a conscious, semi-critical reply to the high-mindedness of 12 Angry Men. Its author was Ernest Kinoy, whom I would single out as the key writer of The Defenders – even more so than Reginald Rose, and in fact it’s possible that Kinoy’s first-season scripts (which also include “The Best Defense”) influenced the direction in which Rose took the series. Something of a legend among his peers, Kinoy won Emmys for The Defenders and Roots, and reliably wrote the best episodes of half a dozen series in between. An adoptive Vermonter for most of his professional life, Kinoy kept one foot out of the industry; he’s semi-forgotten today, and I deeply regret that he never used one of those Emmys as leverage to get his own series on the air. Rose and story editor William Woolfolk acknowledged him as the only Defenders contributor who always turned in shootable first drafts; the filmed versions of these suggest that Kinoy had an ease with naturalistic dialogue and realistic behavior that made other good writers’ work seem phony or overwrought. Like The Defenders itself, Kinoy kept getting better as he went along; his greatest triumphs were “Blood County” (a clever allegorical treatment of violence against civil rights activists), “The Heathen” (a defense of atheism), “Blacklist,” and “The Non-Violent” (with James Earl Jones as a Martin Luther King, Jr. figure), all from the second and third seasons.

The infamous abortion episode, shown in April 1962, was The Defenders’ trial by fire; I wrote about it in detail in 2008, when Mad Men wrapped a “C” story around it. Produced in the middle of the season, “The Benefactor” endured its sponsor revolt and aired as the third-to-last episode. Positioned as such, it’s something of a moral and aesthetic cliffhanger: the culmination of The Defenders’ evolution from a brainier version of Perry Mason to courageous political art.

I hope that by writing this I haven’t rained on the parade of everyone who has been looking forward to seeing The Defenders, or even sabotaged the show’s chances of continuing on DVD. (Shout Factory, its distributor, has indicated that future releases depend on the sales figures for this one.) Even the weaker episodes have something to offer, whether it’s the gritty New York atmosphere or the chance to spot important Broadway and New Hollywood actors a decade or so prior to their next recorded performances.

(Some favorites: Gene Hackman as the father of a “mongoloid baby” in “A Quality of Mercy”; an uncredited Godfrey Cambridge as a prison guard in “The Riot”; Barry Newman as a reporter in “The Prowler”; Jerry Stiller and Richard Mulligan as soldiers in “The Empty Chute”; Roscoe Lee Browne as the jury foreman in “The Benefactor”; James Earl Jones, above, as a cop in “Along Came a Spider”; Gene Wilder as a waiter in “Reunion With Death.”)

Rather, my purpose here is to preemptively shore up the reputation of The Defenders in anticipation of contemporary reviewers who may note the early episodes’ creakier elements and wonder, “What’s the big deal?” The Defenders’ first season has a rough draft feel; it tests out all the blind alleys and bad ideas and rejects them in favor of greater complexity and commitment and innovation. The first season is a journey; let’s hope that Shout Factory gives us the destination.

Note: The frame grabs illustrating this post are not taken from the DVD release, which hopefully will look better.

The Senator: An Oral History

July 25, 2015

Last month, I wrote about The Senator, an Emmy-winning political drama broadcast during the 1970-71 season as part of the umbrella series The Bold Ones, for The A.V. Club. The Senator is about as old a television series as you can find where nearly all of the major creative personnel are still alive, and I was fortunate enough to interview most of them: producer David Levinson, associate producer/director John Badham, writer/director Jerrold Freedman, writer David W. Rintels, and editor Michael Economou. (I didn’t speak to the show’s star, Hal Holbrook, but the recent DVD set includes a terrific new half-hour interview in which a fiery Holbrook recounts his memories of the show.)

Because the vast majority of the material I gathered wouldn’t fit into the A.V. Club piece, I’ve compiled it here in the form of an oral history. It covers the standalone pilot film, A Clear and Present Danger; the development of the series; and then the individual episodes, at least half of which are little masterpieces from a period when quality television drama was scarce.

Jerrold Freedman: It probably got started with Jennings Lang, and Sid Sheinberg. Probably two thirds of NBC’s product came from us [Universal], and Jennings Lang was a great salesman. By the time we got going on these shows, he had moved on to the feature side. But he had been the guy who invented World Premiere and all these other things. It was a way to get a lot of different shows going with the idea that if one of them caught fire, they could make a regular series out of it. You could also do things and take chances with a six- or eight-episode series that you couldn’t do with a 24- or a 26-episode series. Bill Sackheim created The Protectors, the [Bold Ones] show I did.

Michael Economou: Bill Sackheim was a nice man. My kind of guy. He was very precise when he spoke. Great sense of humor.

Freedman: Bill was a guy who would create shows but he didn’t want to run them. He didn’t want to stay on for the series. Bill was really one of the greatest creator/writers in television. He was up there with Roy Huggins and Stirling Silliphant and guys like that. And he was also a mentor to a lot of us. He was a mentor to Levinson and me and Badham, and Joel Oliansky.

John Badham: I was working for the producer, William Sackheim. He and the writer, who I’m pretty sure was Howard Rodman, had developed a story called A Clear and Present Danger, before the Tom Clancy novel of the same name, and dealing with something that at the time some people said was ridiculous.

David Levinson: I forget the genesis of it. Someone had come in and proposed the idea. I think that [S. S.] Schweitzer came in and proposed the idea. A. J. Russell came in behind him, rewrote the story, wrote a script that was not very good, and they brought Howard [Rodman] in to write the script that ultimately became the pilot. I think it’s all Howard.

Badham: Why were we doing a story about air pollution? Because it was just not widely recognized as any kind of a problem, and yet Bill Sackheim and Howard Rodman had a strong belief that it was a serious problem, and they built it around the character of, I believe, a high level attorney in the Justice Department. That character was cast as Hal Holbrook, and as the story follows, [there are] some really serious air pollution attacks around cities of steel mills and big industrial sites, and the resulting waves of illnesses that came from it with people getting really sick and so on. The Holbrook character’s effort to bring law into this, and the difficulties, because as I said people didn’t regard this as a problem, and we were able to utilize that as part of the resistance in the program. You would think that the bad guy would be the air pollution, but it was the people surrounding it. To make a kind of silly comparison, the bad guy in Jaws could be either the shark or a silly, stupid mayor who doesn’t want to shut the town down because it might hurt tourism. The industrialists who owned a lot of these big industrial sites [were] saying, “Listen, hey, you’re going to shut us down? We’ll just move to China. We’ll just move to another state.” So that was the subject of it.

The director was James Goldstone, a wonderful, very creative director, who took the crew to Birmingham, Alabama, which I had recommended to them. I grew up in Birmingham and that was a heavy, heavy industrial steel-making city where the sky would be ablaze at night with the furnaces going. Very beautiful sight, but my father had terrible emphysema because of living his entire life in Birmingham. God knows how many people had been affected by it over time without really realizing what was going on. Goldstone shot in Birmingham for about a week, but as soon as U.S. Steel got wind of it, they started sending their security guys out to move us away from whatever sites we had picked, which probably had steel mills in the background. I don’t think we were ever on U.S. Steel property, but you could see these great furnaces going. They basically chased them off, and for a couple of days Goldstone drove around town shooting out of a van. Secret plates that he would use for backgrounds back in the studio, so that when they go to meet with the head of this fictitious company, in the windows behind him you could see these things going nuts and blazing away as he’s saying, “We’re not going to change anything other than move our steel mill to another city, and you guys are out of luck.” So the film was very, very strong, and really a good wake-up call.

In 1970, The Bold Ones added to The Senator to its roster, in place of The Protectors, for reasons that were never explained to its producer.

Freedman: Maybe the ratings weren’t as good as the other two shows it was with. I don’t know. One of the protagonists was black; I always wondered if that had anything to do with it. The other two shows were what, The [New] Doctors, and that stayed on for a while, and then the other one was The Lawyers, with Farentino? I think that those were more popular casts. We had Leslie Nielsen, who was a great actor but back then didn’t have the name power of some of these other people.

Levinson: I was given the show by Sid Sheinberg. Bill Sackheim was not able to produce a series. He had contractual obligations that prevented him from doing it, and he agreed to stay on if I became the producer. So it was his largesse that really got me the show. I had done a couple of seasons of The Virginian, and I had done one television movie. But basically this was going to be my trial under fire.

David W. Rintels: They had some very good people over there. Not only Bill Sackheim, who would fight for it, but a very good line producer, who really functioned on a lot of levels, David Levinson. They had pride in what they did, and Hal Holbrook had pride, and Michael Tolan.

Levinson: Sackheim rarely wrote anything himself. But his genius, and I’ve said this for years, was getting in really good people and then somehow drawing out of them the very best they had to offer. Any number of people I can name who were really successful writers and directors did their best work with Bill. He was my role model.

Badham: In all of the episodes, he was always there. More in the form of a consultant than anything. David Levinson was clearly the boss and the leader, but he always included Bill in script decisions and reading scripts and looking at cuts and getting Bill’s feedback and input.

Freedman: Universal turned out tons of great filmmakers, because they were really willing to give young guys a shot. We had Huggins, we had [Jack] Webb. It was a mixture. But they weren’t averse to young people, and most other studios were averse to young people. It was hard to get in as a young person, much different than today. I was the youngest producer in the business when I did The Protectors.

Economou: The thing that was very refreshing was that everybody was under thirty. They were young kids. David Levinson, David Rintels. There was such a heat, such a tremendous energy created.

Levinson: Stu Erwin, Jr. was the studio executive on it. But the truth of it the matter was that whenever we had a major problem with the show I went straight to Sid Sheinberg. I mean, he was the guy that had given me the show, and as he said to me once, would always afford me enough rope to hang myself. He ultimately was the boss.

Freedman: When Sid took over television from Jennings, which was either about ’67 or ’68, I don’t think Sid was more than 35 years old. Sid was a really combative guy. We used to fight like crazy. But he was really a stand-up guy for his people. He would say to me, “Whatever you’re doing, I’ll back you. You and I might fight but when it comes out to the rest of the world, I’m going to be right here behind you.” And he was. He really backed us. And we were doing shows that, in their time, were kind of revolutionary, whether it was The Senator or The Psychiatrist or some of these other shows. There was a lot of pushback from the network on those shows, and Sid was very aggressive about standing up for us.