On the Outer Limits of The Outer Limits

March 1, 2011

You’re a big fan of a TV show and you’ve seen all the episodes more times than you can count. You read the companion book. You memorized the DVD extras. You wore out the internet message board. But it’s not enough. Like any fan of anything, you want more. More stuff like the stuff you love. More stuff made by the people who made the original stuff.

Every cult show has this sort of marginalia: the proto-pilot (“The Time Element”) that Rod Serling drafted a year before The Twilight Zone; the one-season military drama (The Lieutenant) on which Gene Roddenberry employed many of the actors and crew who would eventually staff Star Trek. For fans of The Outer Limits, the short-lived but often astounding fantasy anthology that ran on ABC for a year and a half in 1963 and 1964, there is a tantalizing roster of such tangential media.

The Outer Limits had two fathers, and most of this ephemera adheres to one or the other of them. Leslie Stevens, an entrepreneur and playwright of stage and live television, created the show and wrote some of the episodes with a hard-science fiction bent. Joseph Stefano, the screenwriter of Psycho, produced the first season and fostered the tone of delirious, neo-gothic paranoia that made The Outer Limits truly original.

For Stevens cultists, there’s Private Property, the 1959 independent film he wrote, directed, and produced, starring his then-wife Kate Manx (later a suicide) and Outer Limits guest Warren Oates. There’s Incubus (found revived on DVD a decade ago, with copious special features), a 1965 horror film that Stevens wrote and directed in the made-up language Esperanto, featuring his next wife, Allyson Ames, and William Shatner. There’s Stoney Burke (out of circulation but findable among collectors), the underrated, downbeat modern-day rodeo drama starring Jack Lord, which ran on ABC for a single season just prior to The Outer Limits. And there’s “Fanfare For a Death Scene,” the unsold pilot for a series to be called Stryker, which was produced by Stevens’s company, Daystar, during the run of The Outer Limits.

For Stefano, the more important talent, there is Eye of the Cat (still hard to find, although I saw a print five years ago at the Brooklyn Academy of Music), a pretty dreadful 1969 thriller adapted from an unproduced Outer Limits script. There’s The Unknown (circulating among collectors), an alternate, unsold-pilot cut of the classic Outer Limits episode “The Forms of Things Unknown.” But the holy grail has always been The Haunted, the pilot for an occult drama that Stefano almost sold to CBS immediately after he left The Outer Limits. (The Haunted may be better known under the title “The Ghost of Sierra de Cobre,” a title applied to a longer version shown as a feature in markets outside the United States.)

For years, The Haunted lurked in the shadows, a ghost indeed, taunting Outer Limits fans with its consummate obscurity. Supposedly Stefano himself made the rounds of the archives in his last years (he died in 2006), looking in vain for a print of it. David J. Schow, the author of the exhaustive The Outer Limits Companion, who had not seen The Haunted when either the first (1986) or second (1998) editions of the book were published, put the word out among collectors every few years. Nothing emerged. Then a copy screened at a fantasy film festival in Japan, but reports in English were few. A print surfaced on Ebay, sold for a pittance, and disappeared again.

Finally, early this year, the UCLA Film and Television Archive came to the rescue. A sixteen-millimeter print of The Haunted had resided at the Archive since at least the late 1990s, but few people (especially Stefano fans) were aware of its existence. As with many cultural artifacts that have been overzealously declared “lost,” this was a case where no one had thought to ask the right person. Although UCLA’s print had been transferred to video and was available to visiting researchers, the Archive’s Mark Quigley, one of the Outer Limits faithful, thought that wasn’t good enough. Quigley campaigned for a public screening of The Haunted as part of UCLA’s Archive Treasures series. Last week, paired with a thirty-five millimeter print of The Unknown, The Haunted was given a proper (if belated) premiere at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, with Stefano’s widow Marilyn and other family members in attendance.

*

The Haunted stars Martin Landau as Nelson Orion, a modern architect and “the country’s foremost restoration expert,” who’s more preoccupied by his second and presumably less lucrative career as a “psychic consultant.” In other words, Orion investigates incidents of the paranormal. Are they real, or phony? Orion has detective skills rooted in this world, but also a kind of shining for the otherworldly that’s not fully explained in the pilot. “I don’t believe in ghosts, but I’m afraid of them,” is the epigram that Orion quotes to sum up his philosophy.

In the pilot, Orion’s client is one Vivia Mandore (Diane Baker), a wealthy young woman whose new husband is doubly luckless: Henry Mandore (Tom Simcox) is blind, and he’s being haunted by the ghost of his domineering mother. Vivia hopes to save her marriage by plucking Henry from the grasp of this wraith, who communicates by telephone from her crypt and finally manifests itself in the form of a glowing, skull-faced ghost.

Orion suspects that someone is orchestrating the supernatural goings-on in order to lay claim to the Mandore millions, and fixes his attention on the foreboding family housekeeper, Paulina. But then Stefano’s script pulls a switch: Paulina is not the agent of the haunting, but the target. The ghost is real, and it has a complicated reason for descending upon both Paulina and Vivia, one rooted in their shared secret past.

It’s a shame to puncture the excitement of discovery by pointing out that The Haunted, while fascinating, is a lesser work in Stefano’s portfolio. Although Stefano’s work was always allusive – the demented genius of “The Forms of Things Unknown” is not at all reduced by the fact that the script is a blatant reworking of Clouzot’s Diabolique – The Haunted is built out of a grab-bag of references that fail to cohere. There’s a strain of The Premature Burial (the phone in the dead woman’s crypt) and a very obvious debt to Hitchcock’s Rebecca, in the casting of Dame Judith Anderson as a character initially identical to Mrs. Danvers. And the ghost’s non-corporeal manifestations were probably inspired by Robert Wise’s then-recent The Haunting: a noisy, aggressive poltergeist, physically assaulting a young woman with an unseen energy.

All of these ideas feel recycled, and less interesting than the element of autobiography visible in the character of Nelson Orion. Distracted from his established profession by the folly of ghost-chasing, nagged by a business manager (Outer Limits vet Leonard Stone) who thinks that he’s “squandering” his talent, Orion is a thinly-disguised portrait of Joseph Stefano, circa 1965, a man who had walked away from safer opportunities as a writer and producer in order to launch his own pilots and to direct. Just as Nelson Orion’s career was stunted by CBS’s rejection of the pilot, Stefano’s ambitions beyond screenwriting went unfulfilled.

Part of the problem with The Haunted may be Stefano’s direction, which is stiff and uncertain. Although Stefano had hoped to direct The Unknown (ABC said no), he had not assumed that position initially on The Haunted. Instead, he hired Robert Stevens, a live TV veteran who had directed more segments of Alfred Hitchcock Presents than anyone else (and won an Emmy for the classic “The Glass Eye”). Stevens was famously eccentric (apparently he bowed out of The Haunted because his psychiatrist died), but also a bold visual stylist with a taste for chiaroscuro lighting and smooth, muscular camera movement. Stevens might have fit in with the Outer Limits gang.

In his place, Stefano plays it safe, sticking with more static compositions and flatter lighting than one is used to seeing on The Outer Limits. One reason that interest in The Haunted has persisted is that it reunited much of the key Outer Limits creative team, especially cinematographer Conrad Hall, camera operator William Fraker, and composer Dominic Frontiere. But the dreamy Hall-Fraker imagery is only sporadically evident in The Haunted; it’s a far cry from the wall-to-wall bizarrely-angled, vaseline-lensed, hand-held camera tour-de-forces of their key Outer Limits segments, the ones they photographed for more experienced directors like Gerd Oswald, John Brahm, or Leonard Horn.

Stefano appears to have been hobbled by a low budget, production problems (Henry’s scenes were reshot, with Tom Simcox replacing the troubled John Barrymore, Jr.), inexperience (an attempt at a ghost point-of-view shot comes off crude and distracting), and indecision (apparently Stefano disliked Frontiere’s original score and replaced most of it with cues written for The Unknown). But the biggest problem, I think, is Stefano’s decision to convey the elaborate backstory of Sierra de Cobre – the origins of his ghost – through dialogue, without resorting to any flashbacks. A tale of paranormal mayhem more intriguing than the one we’re actually seeing on-screen is reduced to an indigestible chunk of exposition. This trick had paid off for Stefano before: some of his best Outer Limits episodes (“Don’t Open Till Doomsday,” “The Invisibles,” “The Forms of Things Unknown”) consisted entirely of a few people in an old mansion, talking for an hour. Stefano’s off-kilter writing, coupled with the brilliant imagery laid a heavy air of dread over those episodes. They weren’t talky, they were eery and claustrophobic.

In The Haunted, though, the slack pacing exposes the faults in Stefano’s writing, which in is sometimes verbose and stilted. Was he rushed for time? When nothing else is going on in the frame, it’s hard to not to wince at lugubrious dialogue like this: “Well, you ended the haunting, Mr. Orion. I suppose the only thing that will haunt me now is other people’s anguish.”

Even if The Haunted doesn’t rank among Stefano’s masterpieces, it’s still full of inspired ideas, many of which will resonate especially for the Outer Limits cognoscenti. If your show is about an architect, he pretty much has to live in a cool house, and The Haunted delivers on that promise: Orion’s pad is a talon-shaped promontory jutting out of the side of a deserted beachside cliff. The one iconic composition in The Haunted is a tableau, repeated for emphasis, of the black-clad Paulina, seen from behind, staring up from the rocky beach at Orion’s bizarre hillside domicile. The show’s title sequence is also enormously imaginative, a collage of several images that revealed to be tricks of perpective, most memorably a tidal wave washing over Los Angeles that morphs into a trickle of froth receding on a sandy beach. (Or vice versa – I’ve already forgotten how, exactly, the trick shot works.)

The ghost itself is a spooky image, one created with the same reversal effect as the title character in “The Galaxy Being”; one pilot connects back to the other. Stefano’s ghostly visuals are upstaged by an aural effect, which may be the aspect of The Haunted that fans will remember after all else fades away. The ghostly sobbing emitted by the phone in the crypt is a horrible, nails-on-a-chalkboard sound – not a sound that makes you shiver but a sound that you just want to end, right now, which I imagine is exactly the effect that a real encounter with the paranormal would inspire.

It’s hard to judge a character by just one adventure, but unlike a lot of projected television heroes, Nelson Orion may have been a fellow worth revisiting week after week. Stefano goes out of his way to style Orion as a sort of bohemian; in his own words, “a different kind of cat altogether.” In the pilot this amounts to wearing white tennis shoes and a lot of sweaters; but it’s likely that Stefano had it in mind to position Orion as an outsider with an open mind toward the counterculture. Had The Haunted continued into the late sixties, Stefano might have had some fun with that: a psychic detective in the era of LSD and in the world of beads, nehru jackets, and psychedelic colors. I also dug the presence of Nellie Burt as Orion’s housekeeper and caretaker. Burt was a major discovery in two Outer Limits episodes, a motherly presence who nevertheless carried about her an aura of mystery and forboding. She would have been an ideal mascot for a weekly excursion into Stefanoland.

Stefano works themes into The Haunted that we associate with his work on The Outer Limits – a fixation on suicide; heavy symbolism (Henry’s blindness serves no other function); and in particular an elaborate reaffirmation of the marital bond that is noteworthy for its transparent lack of conviction. Without giving too much away, the conclusion of the pilot sent me back to reread Schow’s excellent coverage in the Companion of “ZZZZZ,” which Stefano revised to reflect his own ideas on marital relations. The Haunted, it should be noted, was expanded for exhibition as a feature overseas, with a different ending that, on paper, sounds more satisfying. The longer cut remains elusive, but Quigley tells me that he is on the hunt.

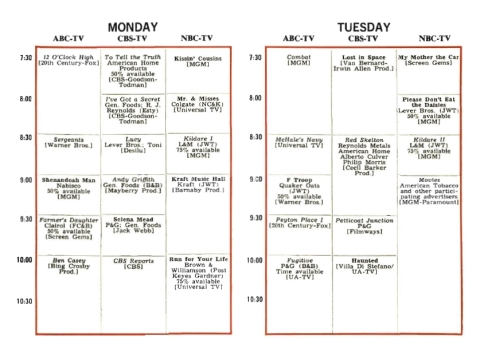

How close did The Haunted actually come to getting on the air? It landed a spot on this draft of CBS’s 1965-66 schedule. There are stories that CBS executives found the pilot too frightening for television, but apparently the show was a casualty of CBS president Jim Aubrey’s ouster in early 1965.

*

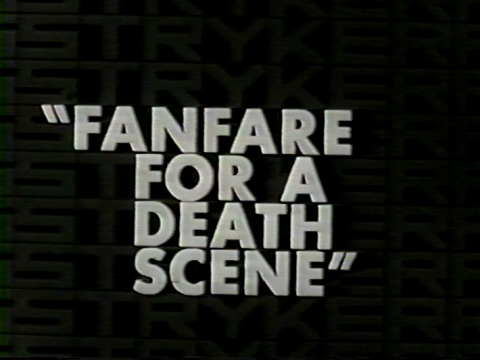

When it rains, it pours: Although the fifty-minute version has existed among collectors for some time, the seventy three-minute, feature-length version of Leslie Stevens’s busted pilot “Fanfare For a Death Scene,” surfaced recently (and without any, er, fanfare at all) amid Netflix’s streaming video offerings.

Cool title notwithstanding, “Fanfare” is a piece of opportunistic hackwork. Stevens created, produced, and directed the show, but farmed out the teleplay to Marion Hargrove, a humorist who captured the light touch of Maverick and I Spy in some fine scripts. But Stryker was to be a deadly-serious cash-in on the James Bond series, and Hargrove foundered, or just took the money and ran.

“Fanfare” stars Richard Egan (off the just-cancelled Empire/Redigo) as John Stryker, a super-powerful industrialist with a direct office line to the president. When that phone rings, he ruefully explains to his secretary (Outer Limits guest Dee Hartford), Stryker toddles off to the far ends of the world on secret spy missions. Like Nelson Orion, he’s mastered his daytime job so thoroughly that he has to find his thrills elsewhere.

Stryker’s mission in “Fanfare” concerns: a nuclear scientist on the lam from a mental asylum; a Mongolian terrorist so villainous that no nation will even admit his existence; an unpleasant helping of torture and violence; implied lesbianism and sadomasochism; futuristic gadgetry, including an omnipresent surveillance device that the villains deploy in Stryker’s snazzy bachelor pad without his ever catching on (thus making our hero look like something of an imbecile); and an oddball cult cast that includes Telly Savalas (yes, playing the Mongolian warlord, complete with Fu Manchu ‘stache), Viveca Lindfors, Tina Louise, Ed Asner, Burgess Meredith (who utters not one line but gets a lot of mileage out of his patented fruitcake expression), and Wo Fat himself, Khigh Dhiegh. Oh, and Al Hirt, nonsensically shoehorned (or just horned?) into the proceedings as a thinly-disguised version of himself.

All of that makes “Fanfare” sound a lot more exciting than it really is. You’re going to want to take my word for this: it’s unremittingly sleazy and dull.

I had planned to sort out which scenes in the long cut I hadn’t seen before, but so much of both versions is “shoe leather” (that is, extraneous side-trips and car and airplane chases) that there doesn’t seem to be much point. Ironically, it’s the long version that ends abruptly, with the death of a minor villain; a subsequent shot of Savalas cackling and vowing revenge was deleted, probably because it too obviously teased future episodes. Another unaccountable omission from the longer version was my favorite scene from the pilot: a quick bit preceding the introduction of Stryker, in which Hartford orders around a pair of undersecretaries. Stryker is such a badass corporate crimefighter, he needs a whole harem of gorgeous, super-efficient executive assistants to do his bidding!

The sad footnote is that the Daystar triumvirate of Hall/Fraker/Frontiere worked on “Fanfare,” too, and their respective talents are much more in evidence than in The Haunted. Frontiere contributes a bouncy, urgent, bright theme for Stryker which I think is original (although I did hear a section of the “oriental” theme from “The Hundred Days of the Dragon” at one point). The variety and scope of the material give Hall a lot of room to show off. Stevens puts the focus on the modernity and power of Stryker’s world, so practically every shot is an extreme low angle gazing up at a skyscraper, a Rolls Royce, a private jet, a gorgeous babe, or a body falling from a concert hall’s balcony. It’s all totally superficial, but Hall and Fraker give their imagery a lot more energy than your average failed television pilot. (See also this addendum regarding the direction of Stryker, which was begun by the talented Walter Grauman. )

The most show-offy shot comes right after the opening credits: a seemingly endless handheld move through a private hospital, past nine drugged doctors and nurses, all draped artfully over various pieces of furniture. The camera comes to rest on the body of the head doctor, who’s fallen into his blotter at such an angle that a pen is jabbing his eyelid open. The gruesome punchline was excised from the TV version, so I guess that’s one reason to excavate this dud from the Netflix archives. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

*

Image from The Haunted courtesy the UCLA Film and Television Archive. Thanks to Mark Quigley, and to all the knowledgeable folks writing for the We Are Controlling Transmission Blog. And speaking of the latter, be sure to check out David Schow and Jeffrey Frentzen’s fascinating account of the creation of The Outer Limits Companion. Their nearly ten-year struggle to complete that project, and the enduring value of the end result, makes me feel a little better about the pace of my own output.

Revised on March 2, 2011, to correct several errors pointed out during an e-mail exchange with Mark Quigley and David J. Schow, primarily my misapprehension that “The Ghost of Sierra de Cobre” was the episode title for The Haunted‘s pilot. It was not – the only title applied to the show during production was The Haunted.

March 1, 2011 at 6:42 pm

Check out http://wearecontrollingtransmission.blogspot.com for a daily discussion of the OUTER LIMITS episodes. Some fascinating posts and comments about the series.

March 27, 2011 at 3:54 am

A very nice and informative reporting.

I am (highly) skeptical whether THE HAUNTED (CBS 1964) would have faired well in a late 10:00 p.m. timeslot against the established powerhouse THE FUGITIVE (ABC 1963-67) as apparently intended.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s I had seen the lengthier 80 minute cut of THE HAUNTED (CBS 1964) aired from time-to-time as a made-for-television film THE GHOST OF SIERRA DE COBRA (1964) on Canadian tv stations.

United Artists Television did have the film version as a tv syndication property.

It would be nice if both the unaired television pilot and the (improvised) film version made available on DVD (standard or blu-ray).

April 29, 2013 at 11:44 am

Considering what Stephen said about this show, maybe it’s better if it’s not on DVD or Blu-Ray DVD (especially for Blu-Ray since MGM would have to create a restored print for both shows, and there probably isn’t the demand, sale-wise, for it to be a DVD in either DVD format.)

April 29, 2013 at 11:48 am

Hey, no matter how bad it is, I’ll still root for a disc release!

July 4, 2013 at 11:29 pm

Speaking of Blu-Ray, considering the enduring popularity of OL TOS, perhaps a joint effort by owner MGM, distributor Fox and

(co-owner? )

http://www.parkcircus.com/films/2202-outer-limits-2-1964-65

might result in a BD box set.

February 2, 2014 at 7:40 pm

I sawthis when I was a child and it absolutaly terrified me, I would love to see ‘the ghost of sierra de cobre’ come out on dvd.

i still get chills when I think about the moaning the ghost made and how it looked….please bring it back

June 1, 2014 at 4:27 am

I saw The Ghost of Sierra De Cobre when I was a child.I hid behind the book case and watched it whilst my 2 sisters and brother sat with my parents.I was primary school age at the time.When the movie finished I was caught and sent off to bed down a long long dark hall way.That movie affected me so much,as well as going to bed in a great big dark empty room,I have never ever forgotten the scenes. I now at the age of 51,always have a torch on hand and have lamps in every room as well as ceiling lights.I always give lights of some kind as a gift,always. I tell my children to always look out for this title incase it comes to DVD as I would love to see it again,I think hoping I will say”is that all it was” when the movie ends but I don’t think so..

August 3, 2018 at 8:44 am

congratulations on using the correct word “affect” and not “effect”.

February 18, 2017 at 12:50 am

I actually loved Fanfare and both Egan and Savalas are fun to observe, likewise Ed Asher (an Outer Limits actor: It Came From Out of The Woodwork) and JD Cannon. The lighting and camera work are astonishing, pure Outer Limits.

August 4, 2018 at 12:30 pm

Is there anyone out there who could make me a dvd copy of Fanfare For A Death Scene? I’d gladly pay for one. I ordered one which turned out to be the short TV version, in poor quality. Amazon.com makes it available for viewing, but not as a dvd.

Jay