Walter Grauman and the Noise of Death

March 23, 2012

My ten-year career as a corporate office drone ended in the following manner: An instant message, sent to my computer screen by a human resources underling, summoned me to a conference room. The room was occupied only by two executives I had never met before. They introduced themselves by sliding a severance agreement across the table. “So . . . tough toimes!” was how the senior executive (a Brit) began his spiel. My boss, to whom I had reported, on and off, for the whole ten years, was not present. He learned that I’d been laid off when I told him.

That day came to mind when I revisited “The Noise of Death,” the seminal, turning-point episode of The Untouchables that blueprinted the series’ transformation from a simplistic cops-and-robbers shoot-’em-up into a richer, more character-driven melodrama. “The Noise of Death” chronicles the fall of one Joseph Bucco (J. Carrol Naish), an aging mafioso who’s being put out to pasture for no special reason, other than change for change’s sake. Nobody tells Joe Bucco that he’s done. They just start doing things around him – collecting extra from the business owners in his territory without telling him, rubbing out miscreants without his approval. Bucco has to ask around to find out what everybody else knows already – that his young rival, Little Charlie (Henry Silva), has taken over. Redundancy – the term that my former corporate overlords favored – is executed not in a hail of bullets from the window of a shiny black sedan, but with a passive backroom shrug of the sort that David Chase would later stage so brilliantly in The Sopranos. (Chase’s series is a mafia text that “The Noise of Death” resembles more closely than the thirties gangster films which inspired The Untouchables). Your final exit has nothing to do with your own record of success or failure. You don’t see it coming. You don’t get to face your executioner.

That’s not to suggest that Bucco does not eventually meet a violent fate. He does, but his final encounter with a bullet is one that is foretold, ritualized, in a manner that the author of “The Noise of Death,” a blacklisted (with an asterisk) genius named Ben Maddow, does not feel the need to fully diagram. The end of Joe Bucco is not motivated by a chain of crystalline events; it moves forward with its own momentum, a momentum that not only cannot be stopped but that also does not appear to be precipitated by any of the players, not even Little Charlie, who stands to benefit from a Bucco-less world. “The Noise of Death” is about the inevitability of fate.

*

It takes a triumvirate to execute a piece as fragile and strange as “The Noise of Death.” A visionary screenwriter, of course, but also a producer who understands the ideas in it and has the courage not to conventionalize them, and a director who knows how to visualize them. Of course, “The Noise of Death” hit the trifecta, or we wouldn’t be discussing it. It marked the initial collaboration of Quinn Martin and Walter Grauman, a producer and director whose sensibilities aligned perfectly; they would work together often for the next twenty years, on The Fugitive and later The Streets of San Francisco, Barnaby Jones, and a number of made-for-television movies.

Maddow’s script for “The Noise of Death,” likely written as an unproduced feature and then adapted for The Untouchables, was eighty-three pages long, an impossible length for an hour-long episode. (The Hollywood rule of thumb is a page per minute.) And yet Quinn Martin put it into production, had Maddow cut it down some and then still let Grauman overshoot during the six shooting days in August and September of 1959.

“I don’t sleep, Mr. Bucco. I dream, but I don’t sleep,” says Bucco’s imbecile henchman Abe (Mike Kellin) at one point. The line is never explained further. It is the most blatant of the many off-beat, quasi-existentalist asides that Maddow interjects in “The Noise of Death.” Grauman or Quinn Martin could have easily breezed past them or deleted them altogether, but both indulged Maddow, carefully underlining his best dialogue and his most radical ideas. Maddow’s real coup is to render Joe Bucco as a sympathetic character, a Lear figure, even as Ness correctly insists that he is a monster responsible for many deaths. There is little, qualitatively, that separates Bucco from Charlie. Towards the end, Little Charlie holds a glass of wine to the lips of a B-girl (Ruth Batchelor) who has mildly defied him, and violently forces her to drink. Charlie laughs harshly, enjoying the moment. The scene clarifies Charlie’s sadism, his inhumanity; and perhaps by this point the viewer has forgotten an earlier sequence in which Bucco casually orders Abe to hop around and imitate a monkey, as a way of demonstrating to Ness the blind loyalty his subjects have for him.

It is not an accident or a flaw that Bucco and Charlie remain nearly indistinguishable. The arbitrariness of Bucco’s removal – a more conventional script would have shown him falling down on the job, being taken advantage of due to his age, but Maddow includes no suggestion of dwindling competence – is what makes him a perversely sympathetic figure.

*

“I want to make something clear to you,” Walter Grauman said to the cast of “The Noise of Death.” “This is probably the best script I have ever read, and there is a rhythm to the speech. So please do not change a word.”

Grauman loved “The Noise of Death.” When Martin sent it to him in June 1959, Grauman read it three times in the same night, so excited by its possibilities that he couldn’t sleep. A relatively untested director, Grauman had done a lot of low budget live television (four years on Matinee Theater), one minor feature, and a few half-hour filmed shows, out of which only a series of Alcoa-Goodyear Theaters indicated his prodigious skill with both camera and performers. Quinn Martin, an equally green producer – a few years earlier, he had been a lowly sound editor for Ziv – saw one of the Alcoas and hired Grauman for his new series about Eliot Ness and his squad of thirties G-Men. The Untouchables would be a hit, would elevate both Martin and Grauman to the big time, although neither knew it yet; “The Noise of Death” was only the third episode on the shooting schedule. (The fact that it was the fourteenth to be broadcast suggests that someone, either Martin or the network, sought to establish the show’s gun-blazing bona fides before loosing the more cerebral entries.)

“The Noise of Death” begins with a flourish, a scene in which a woman in widow’s weeds screams at Bucco from the lawn of his nondescript suburban home. This is the stuff of darkness, and when we next see this woman (Norma Crane), it will be on a shadowy street and then a inside a matchlit meat locker where her husband’s corpse dangles from a hook. But Grauman stages this opener in blindingly bright sunlight, with Crane’s black dress contrasting harshly against the blown-out white brick of Bucco’s house. The contrast between this wraith and her surroundings signals the strangeness that will follow throughout in “The Noise of Death.”

Grauman’s signature shot was a low angle framing of a person, or, more often, a Los Angeles high rise or a Lincoln Continental; power appealed to him, as both a narrative element and a compositional strategy. In “The Noise of Death,” even though he requested that ceilings be built over two sets, Grauman uses his low angles sparingly. There is a corpse-eye view in the mordant morgue sequence, in which Bucco clings to an unforgettable litany (“I respectfully request permission to phone inta my lawyer”) as Ness tries to convince him to turn on the mob, but I prefer the pointed wit in an earlier composition that places the word “cadaver” above Bucco’s head.

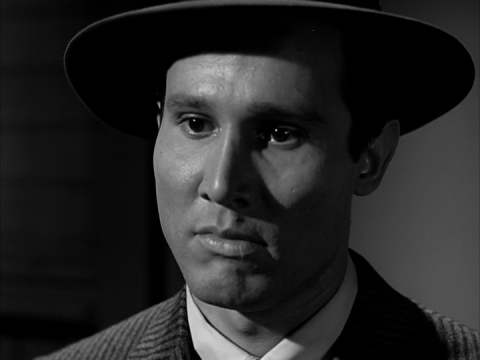

Beginning with the low-angle image of Norma Crane above, “The Noise of Death” assembles a series of unusually powerful close-ups of its players. Like almost all of the sixties episodic A-listers, Grauman was a “total package” director, one who could shape compelling images as well as encourage rich performances from their guest stars. J. Carrol Naish, who played Joe Bucco, was a limited actor, one of those dialect specialists (like Vito Scotti) who usually played ethnic caricatures, often very broadly. Grauman’s chief contribution to “The Noise of Death” may have been to anchor Naish in the realm of reality. Though Naish speaks with a thick accent, it feels authentic, and his wooden-Indian acting translates into a kind of Old World remoteness. As Little Charlie, a young Henry Silva tries out an early version of the stone-faced psychosis that would become his trademark (and grow gradually more campy). In “The Noise of Death,” he’s scary and mesmerizing, and a focal point for Grauman, who felt an instant affinity for the actor. Grauman cast Silva in an Alcoa Theater only a week later, used him as a last-minute replacement for Joseph Wiseman in another Untouchables (“The Mark of Cain”) after Wiseman was badly injured on set, and even wrote an outline for an unproduced sequel that would have brought back the Little Charlie character.

Even whittled down to episodic length, Maddow’s script ran long, and Grauman, working with only a six-day shooting schedule, had to pick his battles. Much of the show plays out in standard television set-ups – static long shots, over-the-shoulders. It is chiefly in the final act of “The Noise of Death” that one feels the confident touch of a strong director at work. The climax of Maddow’s script is a long sequence set in a mostly empty restaurant, in which Bucco finally capitulates and attempts to negotiate a retirement that will permit him to save face. Little Charlie steps into the washroom, leaving Bucco alone for a moment. Slowly, the trio of musicians who have been playing in the background through the scene edge forward, toward Bucco. Are they there to assassinate him, or are they just the band? The answer actually remains slightly ambiguous, but somehow Bucco ends up freaked out enough to duck out onto the fire escape, where a waiting gunman mows him down.

It is an authentically surreal moment, one that Grauman stages and extends for maximum effect. The musicians all have unusual, unreadable faces – the selection of a less interesting set of extras would have ruined the scene. There’s a topper, too: when Bucco stumbles back in through the window after he has been shot, doing a grotesque dance of death, a burlap sack is tied around his head. (Why and exactly how Bucco’s killer has done this is another thing that Maddow and Grauman do not attempt to explain.) Grauman echoes the startling image a moment later, when we see Bucco lying in a hospital bed, his head completely swathed in bandages. In death, he is a faceless man. “The Noise of Death” concludes with a series of cross-generic ideas – the weird forward creep of the musicians; the off-screen murder, indicated only with the violent sound effect of a tommy-gun burst; the out-of-place scarecrow/mummy imagery – which hint that Grauman, whose first feature (1957’s The Disembodied) was a low-budget horror film, may have been under the influence of Val Lewton. Certainly, it’s appropriate that Maddow’s horror over the nature of mafia violence – divorced, much like my corporate severance, from normal human feeling by ruthless procedure or collective psychosis – should bubble up, finally, in the form of images associated more closely with horror movies than with gangster films.

*

Grauman directed eighteen more Untouchables before moving on to other projects (including Martin’s next series, The New Breed), and some of them contain even more dazzling work, especially “The Underground Railway” (an action-packed noir with a heavily made-up Cliff Robertson doing a Lon Chaney-esque tour-de-force) and “Head of Fire – Feet of Clay,” Ben Maddow’s only other script for The Untouchables, which forms a sort of diptych with “The Noise of Death.” (Above I noted Ben Maddow’s status in relation to the blacklist with a qualification; although Maddow spent most of the fifties writing under pseudonyms and behind fronts, the unfortunate truth is that late in the decade the writer brokered an agreement with California Republican Donald L. Jackson, a HUAC member, that enabled him to work under his own name again. Maddow admitted only that he signed a statement, but his friend and former co-writer Walter Bernstein claimed that Maddow named names, including that of a creative collaborator, the documentary filmmaker Leo Hurwitz. In any event, “Head of Fire – Feet of Clay” invites interpretation as an allegory for Maddow’s capitulation, a story of betrayal in which Eliot Ness discovers that an old high school chum [Jack Warden] has been trading on their friendship to extort protection from a vicious gangster [Nehemiah Persoff]. There’s a moment in it where Ness flips over a moll’s handwritten confession, turning the word “evil” into “live.”)

Grauman’s selection of “The Noise of Death” as a career high point implies a certain professional modesty. Some of the cult directors of early episodic television – Sutton Roley, Walter Doniger, John Peyser – were willing to smother a script in technique, but Grauman always protected the writing. Abe’s murder in “The Noise of Death,” for instance, is an abrupt, brutal act, and afterwards Grauman quickly cuts to Bucco, who is seated nearby on a shoeshine stand. The shoeshine boy starts to run away in fear, but Bucco grabs him and delivers another astounding Maddow line: “Go on, boy, finish. Ya start something, ya finish.” Grauman holds on this tableau of man and boy for an extra second, giving us time to register the awful non sequitur of Bucco’s reaction, and to contemplate the boy’s future, the extent to which the witnessing of this bloody act may damage him as he grows to manhood.

Apart from a well-placed close-up of a skipping record, Grauman does very little with the episode’s twist ending, a gag that is transgressive in both its sheer corniness and in the way it emphasizes how ineffectual Ness, the putative hero, has been throughout the story. Grauman so enjoyed Maddow’s punchline that he retold it with relish when I interviewed him more than fifty years later:

Ness has been told a message: go to my vault. He and the guys go to the bank, and they come out with a recording. They go back to their office and the recording’s put on an old-fashioned turntable. Ness puts the needle down on it and it goes scratch, scratch, scratch. “My name’s Giuseppe Bucco, and like I tole you, Ness, I’m a-gonna sing.” Scratch, scratch, scratch. “O sole mio . . .” Ness turns to his cohorts, and they don’t say anything, they just look at each other. He takes the record off and he drops it into the wastebasket, and that’s the end of the picture.

Revised in August 2020 to clarify Ben Maddow’s blacklist status, which I had whitewashed in the initial version (having either forgotten the details or perhaps considered them too tangential to Grauman’s story) and to describe “Head of Fire – Feet of Clay” in greater detail. Upon rereading this piece and revisiting the two episodes, I felt that the ambiguity surrounding Maddow’s exit from the blacklist, which occurred only a couple of years prior to The Untouchables, was a crucial subtext in the two works. Initially this piece was pegged to a public program at UCLA that commemorated Walter Grauman’s ninetieth birthday with screenings of “The Noise of Death” and an unaired version of “Fear in a Desert City,” the 1963 pilot for The Fugitive; I’ve removed a dead link to that event. Walter’s health was already beginning to fail at the time; he died on March 20, 2015, three days after he turned 93.

Notes on sources: Pat McGilligan’s interview “Ben Maddow: The Invisible Man,” collected in Backstory 2, is the key source for the writer’s contested blacklist record. Walter Grauman’s script notes for “The Noise of Death,” shared with me by a mutual friend, provided essential details regarding the episode’s production, as well as a partial list of uncredited actors, which I append here for posterity: Harry Dean Stanton (Newsvendor), Cyril Delevanti (Men’s Room Attendant), Howard Dayton (Peanut Vendor), Ruth Batchelor (Woman #2), Sam Capuano (Mechanic), Karin Dicker (Gabriela), Tom Andre (Boy), Raymond Greenleaf (Banker).

March 23, 2012 at 4:57 pm

I may be wrong, but …

Those three musicians – isn’t the one on the left Aladdin Pallante, from Lawrence Welk’s orchestra?

I seemto recall that he did quite a bit of outside acting on ABC shows during this period.

And he was a violinist.

March 23, 2012 at 6:42 pm

I am currently working on a review of Larry Cohen and Walter Grauman’s WWII spy TV series, “Blue Light.” If you ever get a chance, watch it. The series was limited by its thirty minute format, but deserves mention with “I Spy” and “Mission Impossible.” Robert Goulet is surprisingly good as sacrificing American and arrogant Nazi. Considering Goulet’s later work, I wonder how much of that was Grauman and Cohen.

March 24, 2012 at 12:19 pm

Speaking of “The Fugitive,” Grauman directed 11 episodes of that classic, including what many consider to be the finest of the series: “Landscape with Running Figures.”

March 24, 2012 at 3:42 pm

It would be difficult to understate Walter’s contributions to The Fugitive (for one thing, he recommended Alan Armer for the job of producing it), but I’ve always thought that “Landscape With Running Figures” is overrated. The blindness angle is contrived and Barbara Rush was, in her usual manner, a bit over the top.

March 24, 2012 at 5:22 pm

I have to agree with you about “Landscape” – I’ve always thought Ed Robertson severly overrated it (and I’ve always wondered what the initial choices for Mrs. Gerard – Hope Lange and Julie Harris – would have done with the role). I would also be interested in your opinion of my two favorites Grauman directed – “Ballad for a Ghost” and “The End is But the Beginning?”

March 24, 2012 at 9:57 pm

Fascinating to think of Julie Harris in that role; she’s a wonderful actress. The part needed someone with some sadness (like Vera Miles in “Fear of a Desert City”), whereas Barbara Rush has the air of a Broadway diva. Totally wrong for it, I would say. It’s ironic — miscasting (of Pamela Tiffin) also torpedoed the other really critical Fugitive “mythology” episode, “The Girl From Little Egypt.”

March 29, 2012 at 11:08 am

An excellent, extremely well-attended evening at UCLA, which nearly did not come off due to the recent death of Grauman’s wife, Joan Taylor. In addition to the two television episodes (very strange to watch a Fugitive ep without Rugolo’s theme…), a clip from Grauman’s early “Lights, Camera, Action!” was shown featuring a 19-year-old Leonard Nimoy.

Grauman reiterated much of what’s written above vis-a-vis “The Noise of Death,” and more time was spent discussing it than the Fugitive pilot–which, aside from the missing theme song, also included several items cut from or reshot for the eventual broadcast version. One is a brief scene in Kimble’s hotel room where he’s showing writing an entry into a journal; the other major change is the closing scene between Girard and Monica Welles (Vera Miles).

March 29, 2012 at 11:18 am

Thanks for the report. I should point out, though, that Joan Taylor (aka Rose Freeman) was only married to Walter briefly during the seventies, following the deaths of both their spouses. Walter’s present wife is a bit younger than he is and, so far as I know, alive and well.

As far as I know the alternate version of “Fear in a Desert City” will be on the complete Fugitive DVD, if and when it ever re-emerges.

March 29, 2012 at 12:13 pm

Thanks for the correction, Stephen. The erroneous report came from an overheard conversation. Quinn Martin’s widow was among those in attendance, as well as several surviving fellow directors of the show (most prominent: Robert Butler).

Are/were there supposed to be any other extras in that limbo’ed Fugitive box set? Not that they would do what I’m about to suggest, but I’ve always had a hankering to see a few bloopers from this show…given its inherent tension (as Stanley Fish wrote, “no one can relax”) it would somehow be more enjoyable to see some of these type of moments, particularly between the two principals…

March 29, 2012 at 1:07 pm

Walter is still close to QM’s widow (whose surname is now the same as mine, coincidentally), so that makes sense. I was told that Abel Fernandez, from The Untouchables, was also there. Glad to hear that Butler is still active – good director (and pretty Graumanesque), good storyteller.

I don’t think there are bloopers but, yes, there are a few other extras that were produced for the Fugitive DVD set (including a Grauman commentary on the pilot). There’s a full list of the extras here (and, although I don’t have any solid info to report, I am convinced that this thing will emerge eventually … maybe for next Christmas!):

http://www.tvshowsondvd.com/news/Fugitive-The-Complete-Series/16057

April 15, 2012 at 11:47 pm

I talked with Walter Grauman’s wife at the event that night and she is indeed alive and well. Walter Mirisch was also there, and Grauman talked about being college roommates and lifelong friends with him. It was a great evening!