QM Minus Two

September 17, 2009

Paul Burke and Nancy Malone in Naked City (“Requiem For a Sunday Afternoon,” 1961)

The grim reaper has been working overtime this month: Larry Gelbart, Army Archerd, Patrick Swayze, Henry Gibson, Zakes Mokae, Mary Travers, and the estimable Dick Berg, who granted me a good interview last year. One of the weird coincidences in television history is that many of the major players – actors, writers, directors, crew – from the Quinn Martin factory are or, until recently, were still alive and available for interviews. If you were writing about Bewitched or Ben Casey, you were out of luck, but if you tackled a QM show you could compile a decent production narrative by way of oral history.

Now death finally seems to be catching up with QM, claiming Philip Saltzman (a producer of The FBI and Barnaby Jones) a couple of weeks ago, and now both Paul Burke and George Eckstein over the weekend. Burke, of course, was the second star of QM’s World War II drama 12 O’Clock High, replacing Robert Lansing, whom Martin found too diffident and remote to headline his series. Burke had a more likeable, down-to-earth quality than Lansing, although he was a less gifted actor. He was Leno to Lansing’s Letterman.

Burke had also been the replacement star of Naked City, taking over for James Franciscus in what the New York Times’s obituarist, Margalit Fox, called Naked City’s second season. Technically that’s accurate, but Fox’s phrasing reminded me of how it has never felt true. In my mind, there were two Naked Citys, the half-hour and the subsequent hour-long version. Both sprang originally from the pen of the prolific Stirling Silliphant, and both took great advantage of the practical outdoor locations available in New York City. But the casts were different (save for a pair of supporting players), a full TV season separated them, and the extended length of the later episodes occasioned a major shift in tone.

The Los Angeles Times’s obit for Burke called Naked City “gritty,” but that’s more true of the Franciscus version, a lean, action-centric genre piece that turned Manhattan into a giant playground for foot and car chases. The half-hour City had more in common with other contemporary half-hour crime melodramas – there were a wave of these made in New York City in the late fifties, including Big Story, Decoy, and Brenner – than with its own sixty-minute incarnation, which told character-based stories in a much wider tonal range. The Stirling Silliphant of the first Naked City was the terse pulp writer of Alfred Hitchcock Presents and late films noir (The Lineup, Five Against the House). By 1960, when the hour Naked City debuted, he was the loquacious beat poet of Route 66, a personal writer working an in an ever more idiosyncratic voice. Because not even Silliphant was prolific enough to write both shows at once, he gradually delegated Naked City to Howard Rodman, whose scripts were even more lyrical and offbeat.

If I haven’t said too much about Paul Burke, it’s because he always struck me as a passive personality, just on the good side of dull. That sounds like a knock, but it may have made Burke ideal for the hour Naked City, which required the regulars to step aside most weeks to let some grand stage actor – Eli Wallach or Lee J. Cobb or George C. Scott – take a whack at one of Silliphant’s or Rodman’s verbose eccentrics. One of the best things about Naked City was the relationship between Burke’s Detective Adam Flint and his girlfriend Libby, played by Nancy Malone, that resided on the margins of the show. The pair were friends as well as lovers, and quite clearly (thanks less to the dialogue than to the sidelong glances between the two actors) sleeping together. Adam and Libby were one of TV’s first modern, urbane, adult couples: Rob and Laura Petrie without the farce. Burke may have done his finest work in those scenes.

*

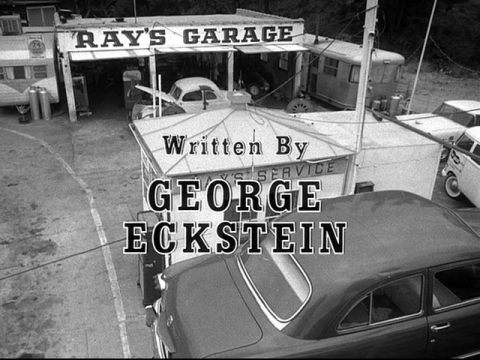

George Eckstein produced Banacek, Steven Spielberg’s Duel, and a number of other important television movies of the seventies. But I suspect more TV fans remember him as a story editor and primary writer for Quinn Martin’s two finest hours, The Fugitive (for which Eckstein co-wrote the two-hour series finale) and The Invaders.

Last month Ed Robertson, author of The Fugitive Recaptured, chastized me for expressing only modest enthusiasm toward Philip Saltzman’s Fugitive episodes, which included one of Ed’s favorites, “Cry Uncle.” Well, I’m relieved to report that Eckstein wrote some of my favorite episodes, chiefly “The Survivors” (about Richard Kimble’s complex relationship with his in-laws), “See Hollywood and Die,” and “This’ll Kill You.”

The latter two paired Kimble, the innocent man on the lam, with actual hoodlums of one variety or another, allowing Eckstein to zero in one of the more intriguing aspects of the show’s premise: how does one live among the underworld of criminals without becoming one of them? “This’ll Kill You” showcases Mickey Rooney as a washed-up, mobbed-up comedian, whose infatuation with a treacherous moll (the great Nita Talbot) leads him to his doom. It seems like every TV drama of the sixties wrapped a segment specifically around Rooney’s fireball energy; some were dynamite (Arrest and Trial’s “Funny Man With a Monkey,” with Rooney as a desperate heroin-popper) and some disastrous (The Twilight Zone’s “Last Night of a Jockey,” with Rooney as, well, an annoying short guy). Eckstein’s seedy little neo-noir gave Rooney some scenery worth chewing.

I interviewed Eckstein briefly in 1998 while researching my article on The Invaders. Eckstein is only quoted in the published version a few times, because he was incredibly circumspect. Not only would he not say anything bad about anyone, he’d barely say anything at all about them. I suspect Eckstein agreed to talk to me only because I had gotten his number from another gentleman of the old school, Alan Armer, who had been his boss on the two QM shows. I wish I could have asked him more – especially now, as I am just reaching the point in the run of The Untouchables (which I had never seen before its DVD release) when Eckstein, making his TV debut, became a significant contributor. It’s always a race against time.

Can I Get a Banacek on Aisle 5?

April 23, 2008

More days off and more TV episodes logged in. Detective shows were the lingua franca of’70s television, so I’ve gradually been sampling them all, dropping the ones that bore me (McMillan and Wife, Quincy) and sticking with those that managed to achieve something creative within the limitations of the genre. Often that seems to have been an insurmountable task. Harry O, for example, slid almost immediately into a rote action/mystery formula that had bore little resemblance to the quirky, off-tempo character drama launched by its brilliant creator, Howard Rodman. Kojak is almost completely ordinary, despite having been managed by a succession of writer-producers of impeccable reputation (Abby Mann, Matthew Rapf, Jack Laird). Maybe it was because Telly Savalas (one of television’s unlikeliest stars) was so intent on looking cool that he didn’t want anything but the most generic cop-show cliches cluttering up his periphery.

(I’m pretty sure I’ve added Kojak to the reject list, but I will offer a parting, backhanded recommendation for the tenth episode, “Cop in a Cage,” which pits Savalas against cult movie villain John P. Ryan as an ex-con out to get Kojak for putting him away. It’s one of the most over-the-top showdowns between narcissistic ham actors that I’ve ever seen. Great fun.)

The only series I tackled this weekend that was completely new to me was Banacek, one of the NBC Mystery Movie franchise shows produced by Universal. When the NBC mystery wheel moved the three hits of its first season – Columbo, McCloud, and McMillan and Wife – to Sunday, the network launched three completely new properties in the original Wednesday time slot. Banacek was the only one of those to limp along to a second season. (The flops were Cool Million and Madigan, replaced the following year by Faraday and Company, The Snoop Sisters, and Tenafly – also duds. Although I’d love to see the latter, which starred the wonderfully acerbic James McEachin as a deglamorized African American private eye.).

I was curious about Banacek mainly because it was build around George Peppard, a downsliding sixties movie star I’d always enjoyed for the naked arrogance he radiated during his brief screen career. Peppard was perfect for roles like the Howard Hughes figure in The Carpetbaggers or the proto-nazi World War I ace in The Blue Max, since he seemed to luxuriate in a blatant anti-social quality, an I-don’t-care-if-you-like-me-because-I’m-a-big-star ‘tude that most of his peers held in check until the cameras were turned off. I was hoping Peppard would project his full-wattage movie star id as Banacek too, but in that sense the show was a bit of a disappointment. He’s still pretty aloof and superior, as befits the character, but he also turns on an unctuous charm whenever an attractive woman is around. Somebody must have taken Peppard aside and explained to him about Q ratings.

If Columbo, the template for all the ninety-minute Universal detective series, was a howdunit that revealed the identity of the bad guy from the start, then Banacek tried to top it by being both a how- and a whodunit. Each episode depicts a daring theft before the opening titles, without showing the culprit, and leaves Banacek to ferret out the crook and piece together the details of his or her tricky scheme (usually in an extended reconstruction sequence in the last act).

Like Columbo, it was a format that demanded a lot of its writers. The first couple of episodes revolve around dazzling, seemingly impossible crimes – a football player who’s kidnapped in the middle of a flying tackle (in Del Reisman’s “Let’s Hear It For a Living Legend”) or a freight car that disappears from a moving train (David Moessinger’s “Project Phoenix”). As the first season progressed, the crimes got more and more pedestrian. The show had a strong writing pedigree – it was created by Emmy nominee Anthony Wilson (the son of MGM producer/writer Carey Wilson, he died of a brain tumor a few years after Banacek) and produced by George Eckstein, a graduate of The Untouchables and The Fugitive – but it’s a daunting task to come up with eight perfect heists a year. If you could, you wouldn’t be a TV producer, you’d be, well, a master criminal.

One aspect of Banacek that I like, though, is that (except in the pilot TV movie that launched the series) nobody dies. Banacek is a “freelance insurance investigator” who solves big-ticket robberies and gleefully pockets a big fee from the insurance execs. That meant the show could strike a breezy tone – sending Banacek to bed, for instance, with each week’s female guest star – without having to find some way to desensitize us against a rising body count. Giving Banacek corporate underwriters to work for also spared us the scene of the private eye agreeing to help some impoverished sad sack solve his grandma’s or old army buddy’s or pet schnauser’s murder out of the goodness of his heart. That’s a cliche I’m really getting tired of as I see it used over and over again, even in dark-hearted shows that should know better, like Harry O.

Banacek’s DNA seems to come partly from Amos Burke, the preposterous millionaire homicide lieutenant who solved murders from the backseat of his Rolls in Aaron Spelling’s trash classic Burke’s Law. The most obvious nod to the earlier series is the presence here of the generally insufferable Ralph Manza as Banacek’s chauffeur, Jay Drury, a comic Italian stereotype; Amos Burke also had an ethnic driver, a Chinese man named Henry (Leon Lontoc), as part of his entourage. Manza’s comic relief is rarely funny, and his character makes no sense, given that Banacek travels around the country to solve his cases and would logically hire a local driver in each city rather than pay an annoying sidekick’s travel expenses. But it just goes to show that even a smart series like this one struggled to get across all its necessary exposition without building in some characters for the loner-protagonist to talk to. (Banacek’s other interlocutor was the arch, very gay rare-book dealer Felix Mulholland, played by Murray Matheson. Banacek wore a lot of turtlenecks and the car phone in his Packard was in an unbelievable shade of pastel blue, so I suppose there’s a bisexual subtext to be unpacked if anyone cares to.)

One thing that puzzles me about Banacek is why everyone keeps harping on the title character’s Polish ancestry. Herb Edelman refers to him as “Super Pole” in one episode and (my favorite) Broderick Crawford calls him Bananacek. I mean, it’s not like everybody in Columbo went around pointing out to Peter Falk that he was a greasy little wop – even though Columbo (a blue-collar guy schlumping around among blue-blooded villains) might’ve expected some class snobbery, whereas Banacek is awfully well assimilated into the world of generic rich white folks. I guess it was an attempt to give a pretty bland character a little color in an era of proliferating crime shows where every hero had a gimmick. Cannon was the fat detective, Longstreet the blind detective, Barnaby Jones the old detective. But it comes across as totally forced, sort of like Ironside’s bizarre fetish for chili in the early episodes of that series.

And finally a bit of pedantry: Something that frustrates me, as a historian, about these ninety-minute shows is that while the stories had room for more speaking parts than a typical hour-long series, the credits did not. So you tend to see a lot of fairly prominent supporting players who didn’t receive billing, and whose names have thus been lost to history. Just in these eight Banacek episodes, I spotted a few familiar actors who, back in the day, were probably pretty apoplectic about being left off the credit roll. In “Project Phoenix,” for instance, there’s Stuart Nisbet as the head train guard, and Owen Bush as an engineer. “A Million the Hard Way” (perhaps the strongest first season segment, a casino robbery piece by Batman scribe Stanley Ralph Ross) features the reliable Irish fireplug Judson Platt, a late member of the John Ford stock company, in a sizeable speaking part as the guard in front of whose eyes the million bucks gets boosted. Lewis Charles appears in “The Greatest Collection of Them All” as Reilly, a waiter in Banacek’s favorite restaurant, a part that might’ve been a recurring one if the show had amassed more than a handful of episodes. And it was a surprise and a pleasure to discover my old acquaintance Lonny Chapman, atypically sporting a mustache, turn up in a little unbilled cameo in the pilot TV movie, in a funny turn as a philosophical redneck bartender. Here he is:

So there are a few folks you won’t find mentioned in the credits, or on the IMDb or anywhere else on the internet. But I’d sure love to dig around in Universal’s production records and learn the names of the dozens of other actors who didn’t make the cut.