Stanley Milgram Goes to Medical Center

December 20, 2012

Say what you will about the Warner Archive – and most of my early reservations about its product, apart from the pricing, have evaporated – but give them credit for having some dedicated amateur television historians on the payroll. Not only did they unearth the bizarre backstory behind the 1971 Medical Center episode “Countdown,” but they also located two lengthy, very rarely-seen alternate endings for the episode, and included them on the second season DVD set that was released earlier this year.

Although the credited author of “Countdown” was Don Brinkley, a prolific freelance writer (Bat Masterson; The Fugitive; The F.B.I.) and a Medical Center story editor, the man who crafted many elements of its storyline was the social psychologist Stanley Milgram. Milgram (whom TV fans will recall as the subject of the famous, largely fictionalized biopic The Tenth Level, with William Shatner) was known for two sociological experiments with implications that penetrated popular culture and made him something of a celebrity, at least within academia: the “small world experiment,” which established through an array of remailed letters the idea that each of us is separated by only six degrees of acquaintance; and the famous Experiment 18, which showed that ordinary people will commit otherwise unthinkable acts of cruelty (in this case, electric shocks administered to strangers) simply because an authority figure instructs them to do so. Even though the supposed electroshock victims only pretended to suffer, Milgram’s work was condemned by many as unethical, because the shockers weren’t told what was really going on and some were plainly traumatized by their own conduct. The experiment that Milgram would devise for – or rather, within and around – Medical Center had a similar whiff of sadism.

“Does television violence serve as a model that stimulates the production of violent acts in the community?” That was the opening line of Milgram’s research proposal, dated April 23, 1969. Milgram’s pitch was a result of a meeting convened on March 29 by CBS’s Office of Social Research, in which its chief, Dr. Joseph Klapper, solicited grant proposals on the subject of violence on television. Not much has been written about the Office of Social Research, but it existed for a long time at CBS – from the days of radio in the forties until at least the late eighties – and it appears to have been a pet project of Dr. Frank Stanton, the highly influential CBS president who over saw most of the network’s scientific, political, and journalistic endeavors. Although it’s hard to imagine a media conglomerate underwriting such a high-minded enterprise today, the OSR actually served two important purposes for CBS. First, it collected early demographic data. Second, following the 1961 Senate hearings on televised violence, it focused upon that topic and became an entity to which the network could point whenever it needed to remind someone that it was properly concerned about the social impact of its programming. In 1969, the OSR awarded Milgram a sum of $260,000 to design and execute a study that would in some way demonstrate the connection (or lack thereof) between violence on television and in real life.

Milgram began with some false starts before he connected with Medical Center. First, he wanted to deprive a community of “any violence shown on television” for an extended period of time, and measure the effects. Needless to say, this proved impractical. Next Milgram commissioned a script for a television movie that would offer a solid, easy-to-emulate act of violence within its narrative, but the script proved deficient (Milgram did not explain precisely why). Eventually Milgram came to the conclusion that the violent stimulus could be less conspicuously embedded within an ongoing series. Surveying the shows on CBS’s 1969 prime-time schedule, Milgram rejected saccharine sitcoms like Family Affair as well as programs like Mannix or Mission: Impossible, which were so routinely violent that isolating a specific act for study would be problematic. Finally he settled upon Medical Center, a popular doctor drama in which a violent act could fit believably into a storyline but still stand out within a show that was typically rather talky. In December 1969 Milgram met with the show’s executive producer, Frank Glicksman, and producer, Al C. Ward, and found them amenable to the idea. The Milgram-infiltrated episode was slotted into the next season, Medical Center’s second.

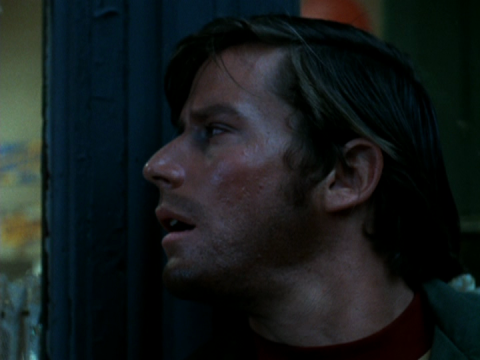

For his study to work, Milgram needed the episode to contain an anti-social act – a clear moral and legal transgression – but one that did not involve violence against another person. (Naturally, Milgram didn’t want to be on the hook for suborning murder!) Milgram and Brinkley settled upon a series of minor thefts as the climax of the episode, which was originally entitled “Give and Take” (and changed to “Countdown” sometime after the script was complete). Their guest protagonist, Tom Desmond (Peter Strauss), would be a young hospital orderly beset by financial and personal problems, as well as a serious inability to control his temper. Too proud to accept the help of friendly Dr. Joe Gannon (Chad Everett, the star of the show), Tom instead notices that collection boxes for a charity have been placed around the city in various locations, in connection with a telethon. (Coincidentally, Dr. Gannon is helping to run the charity drive; implausibly, the boxes are stationed in places like a seedy waterfront bar.) Will Tom bust into one or more of the boxes and steal the cash he needs to pay his wife’s medical bills and bail his charter boat out of hock?

Here is where CBS’s infusion of cash – an amount roughly equivalent to the budget of an entire Medical Center episode, although some of it went to staff and facilities for Milgram’s audience testing – came into play. Milgram turned his Medical Center entry into a Choose-Your-Own-Adventure, concocting three different endings, in each of which Tom made a different choice and suffered a different set of consequences. These were not little codas appended as epilogues. Three highly variant alternate versions of the last act of “Countdown” were filmed, adding (in my estimate) at least two or three shooting days to five- or six-day production schedule.

Milgram designed the endings to dramatize distinct moral outcomes: two “antisocial” scenarios, in which Tom does or does not suffer punishment for illegal actions, and one “prosocial” scenario in which he commits no crimes. In the first “antisocial” version, Tom smashes the charity boxes, steals the money, and loses everything – his wife, his boat, his freedom – only to learn that Dr. Gannon had already gone behind his back and paid his debts. In the second, he steals the money and succeeds in fleeing to Mexico, where his wife (Brooke Bundy) will join him after she is discharged from the hospital. And in the “prosocial” ending, Tom opts at the last minute not to steal or to vandalize any of the charity boxes; in the last shot, he drops a coin into one of them. With the variant “antisocial” endings, Milgram sought to determine whether the factor of punishment affected imitative behavior; with the “prosocial” ending, he expected to measure whether the mere contemplation of a crime could inspire viewers to commit that crime. As a control, Milgram selected an entirely different episode, choosing one as anodyne as he could find, with no imitable anti-social behavior. (Initially Milgram used the first season’s “The Fallen Image,” a soapy Cold War romance with Walter Pidgeon and Viveca Lindfors; for later stages of the experiment, he substituted the newer “Edge of Violence,” with comedian Jack Carter cheering up a possibly suicidal Joan Van Ark.)

Jail, redemption, or Mexico (the latter outcome relayed by the proxy of Tom’s ill wife): each of the three scenes above is unique to one of the different endings of “Countdown.”

One aside that’s worth pointing out is that the Warner Archive disc does not accurately describe “Countdown”’s alternate endings, and presents them in a way that will confuse the viewer. An art card characterizes the endings as “negative,” “positive,” and “neutral,” but the terms “positive” and “negative” do not correspond to Milgram’s terminology, and “neutral” is misused – Milgram used it to describe his control episode, not one of the “Countdown” variants. It’s hard to discern just what Milgram was trying to achieve with each ending from the limited context provided on the disc. (But now you know!) Also, while the discs indicate that “most of the nation would view the … episode in which anti-social behavior is punished,” which I believe is accurate, Warner Archive presents this as one of the alternates. On the disc, the standalone version of “Countdown” is Milgram’s “prosocial” cut, which was probably seen by a smaller audience in 1971 than either of the other two. But what about reruns? The likelihood is that the “antisocial with punishment” version was the one intended for mass consumption. (Its script presented first in the appendix of Milgram’s book about the study, and the other two seem unsuitable for mainstream audiences. The “prosocial” ending is talky and pat even by Medical Center’s standards. And if not for the Milgram exemption the film noirish version in which Tom slinks off to Mexico, and his wife unapologetically vows to abet his escape, probably would have been disallowed by CBS’s censors.) If the complete version presented on the DVDs is indeed the same one used in syndication, then for decades viewers have been watching the dullest version of “Countdown,” probably contrary to the producers’ intentions.

Once “Countdown” was in the can, the mind games that Milgram crafted around it took a variety of forms. In the first round of tests, he showed the different versions of “Countdown,” plus the control episode, to preview audiences in New York City recruited off the street or through newspaper ads. These viewers, thinking their role was only to evaluate the program as a kind of test audience, were promised a transistor radio as compensation, to be collected within a week’s time at a different location (an office building at 130 West 42nd Street, in the heart of the then-scuzzy Times Square). When they arrived there, the subjects were met with a variety of stimuli that correlated to the “Countdown” scenarios. The prize distribution office was unstaffed, and a note left on the counter told prizewinners either that the radios had all been given out, or (in a version meant to be less frustrating) that they were available at an alternate location. On the wall, a charity box similar to the one in the episode held a small amount of money. In one variation, a dollar bill dangled seductively from the box. (Would the criminally inclined take all the money, or just the dollar that could be had without breakage?) In another, the full Project Hope charity box was next to a similar March of Dimes box that had already been smashed and presumably looted. Still another round of experiments transmitted the various permutations of “Countdown,” via closed circuit television, into a room in which the viewer was isolated with the tempting charity box. All the respondents’ behavior was observed by Milgram’s research assistants via hidden cameras.

(The precise design of these scenarios was apparently proscribed by legal concerns about entrapment, a fact mentioned by Milgram and emphasized by one of his research assistants, Dr. Herman Staudenmayer, in an interview this week.)

An observer’s checklist and images of Milgram’s secret lab (both reproduced from Milgram and Shotland’s book Television and Antisocial Behavior: Field Experiments). Click to enlarge.

Those experiments occurred between the completion of filming in September 1970 and the initial telecast of “Countdown” in early 1971. After the original broadcast of “Countdown” in February, a second survey prodded viewers to copy another aspect of the story. Before smashing the charity boxes in both of the “antisocial” versions, Tom Desmond (a real prince, this guy) twice calls Dr. Gannon’s charity and verbally abuses the telethon operators. Viewers of the control episode “Edge of Violence” and then “Countdown” in Chicago and Detroit on February 10 and 17, respectively, also saw advertisements that solicited donations to Project Hope. Calls to the charity on those nights were monitored by Milgram’s associates for harassment that might be imitative of that in “Countdown.” No one took the bait; the few abusive calls contained no language that resembled Tom’s choice of invective.

Then, following an April rerun of “Countdown,” Milgram went back to the first broadcast survey that had been used with preview screenings. Members of the actual television audience in New York and St. Louis received questionnaires about the episode, which they could redeem in exchange for the radio at Milgram’s disguised lab (where the same will-you-steal-the-money shenanigans ensued). New York saw the ending with Tom in jail; St. Louis got the version with Tom in Mexico. (By the time of the broadcast, Milgram had discarded the “prosocial” ending.)

Milgram and a co-author, R. Lance Shotland, published their results in 1973, in a book called Television and Antisocial Behavior: Field Experiments. Milgram’s biographer, Thomas Blass, suggests that the Medical Center experiment is not widely known in part because Milgram did not correlate it with the large body of prior research on the effects of violence in media. Another reason might be that (as Milgram conceded in his own analysis) it proved nothing in particular, except the rather reassuring idea that even a really, really tempting target provokes theft in fewer than ten percent of cases. Not only did viewers of “Countdown” not steal money in significantly greater numbers than the control group, but in several of Milgram’s simulations, people who saw the neutral program stole more often than whose who saw “Countdown.” To the extent that his methodology was valid, Milgram’s experiment indicated that violence and lawbreaking on television were unlikely to contaminate the audience (a fact that no doubt relieved, but probably didn’t surprise, Milgram’s backers at CBS).

In their book, Milgram and Shotland pointed out certain flaws in their methodology – but there were other, more obvious problems to which they did not call attention. For one thing, the puppet-strings aren’t very well concealed. Even though the experiment cleverly cast its guinea pigs as television critics rather than test subjects, wouldn’t many of them have suspected something was up when a scenario almost identical to the climax of the program they’d been asked to evaluate presented itself in real life, during the evaluation process? This was well after the heyday of Candid Camera, and I have to suspect that many of these folks were dissuaded from taking the dangling dollar because they fully expected Allen Funt to appear the second they touched it.

Also, since Milgram conducted the broadcast portion of his experiment during spring reruns – presumably, CBS’s indulgence did not extend far enough to allow Milgram to tinker with programming during the regular season – then at least some of his subjects must have seen “Countdown” prior to the evening on which they were asked to evaluate it. Mightn’t many of them have remembered the show and filled out the questionnaires without watching the rerun all the way to the end? That would mean that they had observed Tom’s criminal act months rather than days prior to being tempted themselves.

(I think that viewers in Milgram’s broadcast experiments saw “Countdown” in both February and April of 1971, but it’s difficult to be completely certain. Milgram and Shotland’s book indicates that “while most of the country saw a neutral episode,” twelve million viewers in the New York City area watched “Countdown” on April 28 as part of the free radio experiment. An unidentified control episode was surveyed the week before. However, in the section on the call-in experiment, Milgram and Shotland suggest that a control episode and then “Countdown” aired, respectively, on April 14 and 21. Unless I’m missing something, that’s an internal contradiction in their book. TV Guide’s listings in its Metropolitan New York edition and the TV listings of Long Island’s Newsday both give the following airdates: February 10, “Edge of Violence”; February 17, “Countdown” (meaning that the April broadcast used in the study was definitely a repeat); April 14, a rerun of “Trial by Terror”; April 21, a rerun of “Death Grip”; April 28, a rerun of “Junkie.” If Milgram and Shotland’s account is accurate, then “Countdown” was substituted in New York for either “Death Grip” or “Junkie,” without notice to that effect in the local listings. That’s certainly plausible, given the amount of influence Milgram had with CBS. However, I am puzzled by the dates given in Milgram and Shotland’s book for the St. Louis broadcasts: April 12 and 19, two days before the corresponding New York airdates. How on earth was St. Louis watching Medical Center on Monday nights instead of Wednesdays?)

From a historical perspective, the behind-the-scenes story of “Countdown” holds more interest than the results of Milgram’s experiment. Even Milgram seemed to understand and admit this. “Although the relationship between television violence and aggression was not something Milgram was intrinsically interested in – and, in fact, he harbored some doubts about the existence of such a relationship – the idea of being able to do research on a grand scale appealed to him,” wrote Thomas Blass.

It’s fascinating to map the competing agendas of the network, the producers, and the scientist. CBS purchased a study that, regardless of the results, would serve as tangible evidence of its concern about televised violence. Milgram got to undertake the best-funded research of his career – although in accepting the grant he opened himself up to charges that his objectivity would be compromised.

And why would the producers of Medical Center put themselves through the torturous process of Milgramizing an episode? Ward and Glicksman may have coveted CBS’s extra dollars. Two of the three endings of “Countdown” have more production value on display than a typical Medical Center. There’s an extended foot chase scene, shot on actual outdoor locations and given a noirish flavor by director Vincent Sherman, who had been an A-level contract director at Warner Bros. during the studio’s golden age.

Milgram recorded his frustration with the production of “Countdown.” “At points in the production of the film,” he wrote, “I found myself up against long-established traditions of directing and acting that, because of the group norms of the production team, became virtually impossible to change.” Milgram was present on the set, trying – usually in vain – to get the episode to conform to his needs. He objected to Tom’s “faint trace of inebriation” during the phone calls (in fact, an overacting Peter Strauss plays Tom as completely plastered throughout the climax or, rather, all three climaxes) and to several other story points. Milgram complained that “the director insisted on inserting a chase scene . . . simply for the purpose of livening up the action.” In writing that, Milgram revealed a basic ignorance of the production process. Sherman could not have completely improvised the lengthy chase scene, which involves police cars, extras portraying policemen, and substantial day and night exteriors. Such a sequence would have been budgeted and scheduled well in advance, which suggests that perhaps the producers were keeping Milgram in the dark about some of their intentions, and leaving Sherman to run interference with the good doctor.

Scenes from a chase that Stanley Milgram didn’t want. Sorry, Stan.

It’s tempting to imagine Glicksman and Ward indulging and manipulating Milgram, using his experiment to buy themselves an above-average segment. On the other hand, Milgram was still pulling the network’s puppet-strings – which may have been the whole point all along. Blass points out that “what makes the study unique to this day is that Milgram had control over regular prime-time programming.” Milgram managed to insert his own agenda into a closed capitalist system of popular culture that academia could typically observe only from the outside. The electrocutors and the letter-mailers in Milgram’s famous experiments didn’t know that they were actually his guinea pigs. Perhaps the CBS men who funded Milgram’s Medical Center shenanigans were, without knowing it, the true targets of the experiment.

Sources: Stanley Milgram and R. Lance Shotland’s Television and Antisocial Behavior: Field Experiments (Academic Press, 1973) and Thomas Blass’s The Man Who Shocked the World: The Life and Legacy of Stanley Milgram (Basic Books, 2004). Lightly revised in February 2020 to incorporate research from the Donald Brinkley collection at the Billy Rose Theatre Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, which holds correspondence and multiple script drafts for the Milgram episode (under its original title “Give and Take”).

Filed in TV Controversies

Tags: 1970s television, Al C. Ward, CBS, Chad Everett, Frank Glicksman, Joe Gannon, Joseph Klapper, Medical Center, medical dramas, Milgram experiment, Peter Strauss, R. Lance Shotland, social psychology, Stanley Milgram, television dramas, television violence

December 20, 2012 at 2:36 pm

The Warner Archive write-up for the MC season 2 set that mentioned the three endings for “Countdown” was mystifying to me when I first read it, but thanks to you, now it isn’t.

Incredible stuff. A well-researched effort of yours!

I only knew of Milgram’s Experiment 18, so this subsequent bit of (flawed) research was interesting to read about, too.

Which of the endings worked for you best?

December 20, 2012 at 4:06 pm

Wow, I can’t believe I never knew anything about this. What a fascinating story. I was a regular viewer of MEDICAL CENTER during its TNT days, and though I recall this episode, I don’t remember its ending. It would be interesting to hear what Strauss has to say about the episode. He may be the only principal still alive.

December 20, 2012 at 5:18 pm

Strauss and Brooke Bundy are both still around, but I was more interested in contacting someone who worked with Milgram at that time. Unfortunately, R(obert) Lance Shotland didn’t return calls, and I couldn’t get a number for Milgram’s widow (who is still alive, though).

December 26, 2012 at 2:07 pm

Stephen, this is ClassicTVHistory at it’s best. Very compelling piece. Nice job.

January 20, 2017 at 12:09 am

I have been streaming MC from Warner Archive and at the end of the this episode, instead of going back to the summery, it stayed black and then showed “alternate ending B” and proceeded to show that alt ending and then C. I thought “well, this is highly unusual” and googled for info about it and found your blog. Thanks for the info. I never got the DVD’s so I never had the liner notes.