Shane

November 30, 2023

Like the following season’s Hondo, Shane (1966) is probably remembered, if at all, as one of those ill-conceived attempts to turn a movie classic into a television hit – a sheepish bit of intellectual property-mining that quite properly slunk off the airwaves after thirteen little-watched weeks. In fact, this unduly forgotten and mostly still unrediscovered series was one of the best Westerns to mosey along after the genre’s late-fifties television boom had turned to bust. It’s a smart, carefully made show, one with a distinctive visual style and stories that engage in substantive philosophical and political contemplation. Variety, in a tone that may or may not have been pejorative, characterized it as an “intellectual western.”

Shane was the first (and, as it turned out, only) series to emerge from a major realignment of the prominent independent producer Herbert Brodkin’s operations. After a long association with CBS that included Playhouse 90, The Defenders, and The Nurses, Brodkin’s agency, Ashley-Famous, had negotiated a liaison with ABC, still the ratings and carriage underdog among the big three. Meanwhile, Brodkin had sold Plautus Productions, owner of The Defenders and his other pre-1965 output, to Paramount, and had at least informally moved his operations under the film studio’s umbrella. It was a classic “what were they thinking?” acquisition, and the relationship would sour quickly, as Brodkin’s parsimony, contempt for hit-making, and general intractibility became apparent to his new corporate partner. But for a brief moment in 1965, the venerable movie studio saw Brodkin as the potential rainmaker it needed to catch up to MGM, Warner Bros., Fox, and Universal in the television market.

Just as Twentieth Century-Fox was doing concurrently (with The Long Hot Summer and Jesse James), and Warners (Casablanca; Cheyenne) and MGM (The Thin Man; Dr. Kildare) had done a decade earlier, Paramount that year initiated a “crash expansion” (Variety) of its television production by looking for entries in its back catalog of features that could be quickly adapted into ongoing series. Houdini, The Tin Star, and a Stirling Silliphant-scripted, serialized (in imitation of Peyton Place) reworking of Sunset Boulevard were all developed for television. (Who cared that a big-budget TV version of Paramount’s Oscar-winning The Greatest Show on Earth had flopped only a season ago?) Shane, the 1953 prestige western about a brooding gunslinger’s impact on the members of a young frontier family, was another obvious choice, and Paramount farmed it out to Brodkin’s new company, Titus Productions. In June 1965, Brodkin commissioned a pilot script from regular Nurses writer Leon Tokatyan.

Brodkin’s big debut of the 1966 season was supposed to be The Happeners, a topical look at the Greenwich Village arts scene that centered on a trio of folk musicians (vocalist Suzannah Jordan, plus Craig Smith and Chris Ducey, who later recorded as the Penny Arkade and retain a minor cult following among ’60s pop aficionados) and aped the flashy, disjointed look of Richard Lester’s Beatles movies. Instead ABC nixed the $400,000 pilot, citing advertiser disinterest, although I wonder if they were in fact spooked by NBC’s rival project The Monkees (or perhaps by Plautus’s last CBS series, Coronet Blue, a hard-to-describe adventure series that also feinted in a Mod direction, which so baffled the network that all 13 episodes were shelved for two years). ABC’s rejection of both The Happeners and another Brodkin pilot, the international-intrigue story One-Eyed Jacks Are Wild (with George Grizzard in dual roles as a Chicago gangster and a European prince), triggered a “one-for-three” contractual clause that forced the network to pick up Brodkin’s next pitch, no matter what it was. One imagines Brodkin forcing something even more esoteric into production out of spite, but, perhaps hoping to salvage the relationship or just in need of a hit, the producer went with Shane, which was commercially safer and likely cheaper than either of its more ambitious predecessors. Even placing a safe bet, Brodkin floated perversely uncommercial notions, like changing the title to keep the star in line (“If you named your lead character Shane, you can’t ever fire him. If you named it Western Streets, you can”). He lost that one. The pilot script was set aside (or it may have morphed into the episode “An Echo of Anger,” on which Tokatyan has a pseudonymous story credit) and Shane went straight into production.

The creative group in charge of Shane was an amalgam of Brodkin’s talent pool from New York (including half a dozen favored writers and directors he had used on The Defenders), plus a pair of Los Angeles-based young men with bona fide video oater experience: producer Denne Bart Petitclerc and story editor William Blinn. Both were recent Bonanza alumni. Petitclerc and Blinn reported up to David Shaw, who had evolved into the de facto showrunner of The Defenders at some point in the back half of the show’s run, after creator Reginald Rose scaled back his involvement due to exhaustion. Shaw – forever in the shadow of an older brother, Irwin, who after the war had become one of the country’s most prominent prose writers – had been a live TV playwright of moderate stature, associated with the Philco/Goodyear Playhouse during the period when its impresario, Fred Coe, was nurturing the likes of Paddy Chayefsky, Horton Foote, and Tad Mosel. Shaw’s work, though generally of high quality, had few of the overtly personal themes that made those writers’ reputations. Brodkin made him a partner in Titus Productions and Shaw leveraged the Shane job to pay for a move from the Big Apple’s dwindling prime time industry to Los Angeles, where he lived for the rest of his life.

(I met him there by chance one day in 2004 in the Century City Mall. I recognized Shaw’s second wife, the character actress Maxine Stuart, and followed them into a pharmacy, awkwardly introducing myself while they waited for their prescriptions. A nice man, Shaw later endured an interview, although he had long since shifted his creative focus from writing to painting, and seemed unencumbered by nostalgia for his television career. “Stupid idea,” he said of Shane. “I mean, Shane is a guy who travels around. You couldn’t have that [in a weekly series]. And we built a set. He was always about to leave and then he has to stay, every week.”)

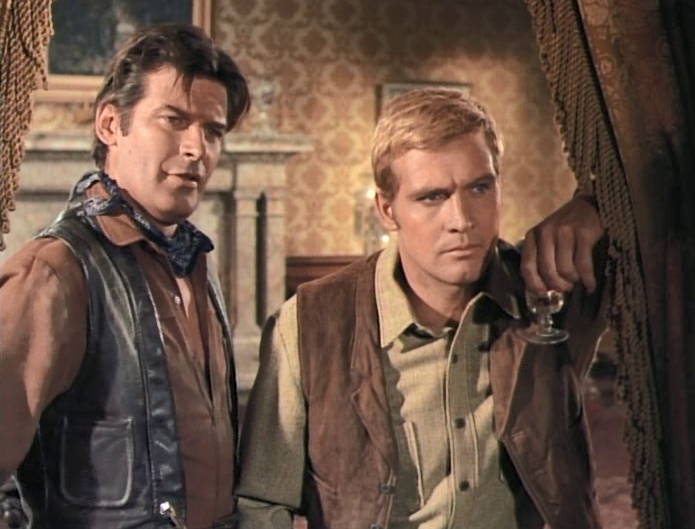

Playing Shane was David Carradine, the oldest son of the eccentric character player John Carradine, but a prospective leading man due less to nepotism than to a recent, buzzy Broadway turn as an Inca god in The Royal Hunt of the Sun. In publicity for his new gig, a helpful Carradine disparaged the late Alan Ladd’s performance in the original Shane (“not really an actor at all but a personality” who “brought very little to the film”), and referred in another interview to Shane’s directors as “traffic cops” and its writers as “plotmongers.” He at least bonded with Petitclerc, a Hemingway acolyte and counterculture-adjacent figure who would later create the semi-autobiographical biker drama Then Came Bronson (which also starred a young actor with a talent for putting his foot in his mouth). Cocky or not, Carradine was the real deal, confident on camera and clearly a star in the making, but youthful in a way that contrasted with the world-weariness Ladd (ten years older in his Shane) brought to the character. Carradine cited Steve McQueen as a point of reference, and it’s easy to see McQueen’s opacity and reserve reflected in Carradine’s Shane.

The rest of the cast was hit-or-miss: the English ingenue Jill Ireland, too delicate to believe as a single mother toughing it out on the range, and beefy Bert Freed, an odd actor whose scowling boulder of a face was undercut by a soft voice and a diffident affect, as the villain Rufe Ryker. Freed was the guy you hired after Clifton James turned you down, although on the whole Shane succeeded at getting some Big Bad mileage out of his look alone. Folksy Tom Tully (who had enjoyed a recent career boost in Alan Ladd’s final feature, The Carpetbaggers) counterbalanced Freed as Tom Starett, Marian’s aged father-in-law.

Tully’s character is not in George Stevens’s Shane, and in the television series he takes the place of the character played in film by Van Heflin, the young husband/father. The movie’s most complex dynamic was the rivalry between Shane and Joe Starrett for the affections of Joe’s wife and son; while the boy’s hero worship of the outlaw is overt, Marian’s sexual attraction to Shane (and Shane’s own feelings for his friend’s wife) go largely unstated. The spectre of infidelity, suppressed in the film but perhaps less containable on a weekly basis, would’ve been a touchy subject for sixties television. Shane solved that problem neatly by making Marian a widow, its only significant change from the premise of the film. The other familial element that distinguished the feature – the tow-headed tyke whose point of view sometimes framed the depiction of violence and other adult motifs – remained intact, with the casting of a child actor (Chris Shea) who was virtually identical to the original’s Brandon de Wilde. Young Joey’s anguished cry of “come back, Shane,” from the indelible (and often lampooned) climax of the film, even makes an appearance in the third episode, “The Wild Geese.”

As David Shaw told me, the producers were preoccupied at the outset with making Shane’s clash between drovers and settlers sustainable. Shaw’s script for the first episode, then, reduces the film’s existential battle for the land to a skirmish, over the construction of a schoolhouse which comes to symbolize the permanence of the farmers’ community. This central conflict remains underdeveloped, but a side story in “The Distant Bell,” in which a schoolteacher (Diane Ladd) imported from the East realizes she has no stomach for frontier violence, begins to find the film’s sense of size and danger.

As its makers reprised some of the same topics they had broached in a quite different context in The Defenders, Shane affords a rare opportunity to examine what a leftist western looks like in practice. “Killer in the Valley,” in which plague comes to Crossroads, is a muted critique of capitalism that centers on a sleazy medicine drummer (Joseph Campanella) who exploits the tragedy for profit. Other episodes acknowledge the role of money in society in unexpected ways. In “The Wild Geese,” for instance, the bad guys turn upon one another after the rest of the gang learns that their leader (Don Gordon) is paying his newest recruit, Shane, more than them.

Ernest Kinoy’s “Poor Tom’s a-Cold” offers a progressive colloquy on mental illness, with Shane advocating talk therapy for a sodbuster (Robert Duvall) whose mind has been broken by the hardships of the frontier, while Ryker wants to put him down like a rabid dog. Shane compares Duvall’s character to a spider who keeps rebuilding a misshapen web, unaware that he can no longer conceive of how it should be spun, in the best of a series of compassionate monologues that Kinoy assigns to every character. Ellen M. Violett, the only woman who wrote for The Defenders, contributed a fascinating script about female desire, told from Marian’s point of view. The relatively weak lead performances (from Ireland and guest star Robert Brown) keep “The Other Image” from being the pantheon piece it might have been, but the ending, in which Shane and Marian work off their unspoken, pent-up sexual energy by chopping an entire winter’s worth of wood together, is brilliant.

Consistently, Shane discovered in its reluctant-hero protagonist opportunities to contemplate and often advocate for pacifism. Petitclerc’s “The Day the Wolf Laughed” is an outlaws-occupy-the-town story in which Shane offers a pragmatic, non-confrontational solution – the bandits entered Crossroads flush with loot and have promised not to plunder, so just wait them out – but Ryker’s boorish pride pushes the gunmen toward carnage. A more typical Western (like Gunsmoke, which did several variations on the town invasion premise) would usually invert these politics, casting the town’s craven merchant class as the appeasers while Matt Dillon or Festus maneuver to secure the advantage in a violent confrontation. Kinoy’s “The Great Invasion” depicts, with sympathy, a veteran so traumatized by the sound of gunfire that he won’t raise a hand to defend himself or others, and his “The Hant” subverts the catharsis of violence even more compellingly as it unveils a diabolical high-concept premise: an old man (John Qualen), the father of a gunslinger Shane shot down years earlier, turns up with a plan not to bury Shane in Boot Hill but to adopt the nonplused protagonist as a surrogate son to replace the one Shane killed. This was Blinn’s favorite episode, and decades later, in an interview in Jonathan Etter’s Gangway, Lord! The Here Come the Brides Book, Blinn enthused about a detail in Kinoy’s script that got somewhat lost in the execution: that Shane had killed so many men he couldn’t remember this one. “Day of the Hawk,” with James Whitmore as a preacher who embraces pacifism to stifle his dangerous, compulsive anger, is more skeptical, offering a cynical outcome in which the clergyman kills a semi-sympathetic character in cold blood in order to, perhaps, prevent an even greater tragedy. Here, too, though, the script (by Blinn and Barbara Torgan) gives Shane an unconventional point of view to articulate, a critique of organized religion as an ineffectual, self-indulgent response to the very tangible problems faced by settlers.

The best Shane episode is probably the sole two-parter (especially the first half), which has, among other things, Charles Grodin, in his first West Coast screen acting job, as a snotty New Yorker who gets his ass whupped (twice) by Carradine; Constance Ford as an extremely butch version of Calamity Jane who nevertheless has a Black male lover (Archie Moore, another veteran of Paramount’s The Carpetbaggers); and the Gatling gun as an explicit avatar of a technological escalation in frontier violence, three years pre-Wild Bunch. Again written by Ernest Kinoy, “The Great Invasion” anticipates the George Hearst storyline from Deadwood. Shane tries to make the homesteaders understand that the encroaching Eastern conglomerates pose a bigger threat to them than their accustomed antagonist, the small-potatoes cattle baron Ryker, but none of them can see the big picture, not even the Starett family. The Cheyenne moguls’ strategy involves hiring a mercenary (Bradford Dillman) to push the ranchers off the land on the flimsy pretext of hunting down outlaws. Kinoy’s target is not only predatory capitalism but also the fearmongering law-and-order politics that often enable it.

If that sounds dry or esoteric, it’s not, mainly because “The Great Invasion” is distinguished by one of the richest villains I’ve encountered in a television western. The conglomerate’s enforcer, General George G. Hackett, is a West Pointer who openly asserts that he is destined for military glory and an articulate gourmand who sneers at his employer for disdaining sweetbreads. He’s insufferable as well as psychotic, an unstable martinet who leads his men (arguably with some effectiveness) by inspiring fear rather than loyalty. Kinoy presents Hackett as at once formidable and pathetic, and Dillman, as good here as he ever was, grasps this contradiction and centers it as the essence of a dynamic and unexpected performance.

Am I going overboard in positing “The Great Invasion” as an allegory, conscious or unconscious, for the clash between Eastern (New York) and Western (Hollywood) sensibilities in Shane? Alongside the tropes I’ve detailed above, a countervailing and fairly compatible strand of sentiment runs through Shane, in scripts both syrupy (Ronald M. Cohen’s “The Silent Gift”) and satisfying (most of Blinn’s). The original Shane is about a frontier family, and it’s appropriate that some episodes should foreground this element (even after subtracting a key member of that family). The best of the domestic entries, “High Road to Viator” (at first titled, much more evocatively, “Blue Organdy”), concerns the theft, by scavenging Native Americans, of Marian’s prized party dress, and Shane’s efforts to recover it. Depicting in some detail the preparations for a three-day journey to another settlement to attend a party – Joey, we learn, has never heard of a piano – “Viator” runs high on warmth and atmosphere, and low on incident.

The family-oriented episodes, in particular, showcase this minimalist aspect of Shane, which seems to have motivated the show’s somewhat atypical formal strategies. Brodkin famously embraced the close-up as the building block of television mise-en-scene, and showed little curiosity about the vibrant New York world outside the courtroom and hospital settings of his CBS hits. Those precepts recur and flourish in Shane, a Western that plays out to an unusual degree in interior spaces, gorgeously amber-lit by director of photography Richard Batcheller (a longtime camera operator who had just matriculated to cinematographer gigs and died young, in 1970), and on the faces of the actors. “High Road to Viator” can plausibly be described as a “bottle show” (a deliberately under-budget effort to offset overages on other episodes), but so can several other Shanes, and the last one, “A Man’d Be Proud,” is a bottle show’s bottle show, a television hour as devoid of add-ons (no guest stars, no off-lot locations or new sets, no stunts) as it is possible to make.

If you ask whether these austere choices reflect profit motive or aesthetic preference, the answer is “yes” – the considerations are basically inseparable. (Compare Brodkin, perhaps, to Roger Corman and Russ Meyer, low-budget auteurs who were given big-studio toolkits and, on a fundamental, psychological level, couldn’t scale up to make full use of them.) A year after its cancelation, Variety snickered about how Titus Productions had pocketed a $30,000 per-episode profit on Shane, never mind the show’s conspicuous failure and presumed unsyndicatability. Blinn, in the Jonathan Etter interview, described a running battle between ABC, which wanted more action on screen, and Brodkin, who wanted them to pay extra for it; in the end, neither won. (Anecdotally, cutting corners to guarantee net income from the license fee seems to have been Brodkin’s business model during his Plautus days too, although I haven’t studied the balance sheets.) In The Defenders and The Nurses the professional settings compelled a claustrophobic feel, and a credible argument could be mounted that the scripts’ consciously didactic approach benefited from the absence of adornment or distraction. What’s remarkable about Shane is that, rather than showing up Brodkin as an indifferent cheapskate, it makes the same minimalism work just as well within a genre that typically opts for expansiveness.

It can be difficult, at a remove of decades, to assess a network and a studio’s commitment to a given project, but one reads between the lines and guesses that by the time it premiered in September 1966, Shane was a burnoff. Scheduled for the 7:30 slot on Saturday nights, it was predictably creamed by Jackie Gleason, although the third competitor – NBC’s Flipper – also trounced it, underlining the difficulty of marketing a western as wholesome family fare. (A few years later The Waltons and Little House on the Prairie would solve this riddle by keeping the period survival-struggle elements of the genre and ditching the rest.) By October the trades were already guessing at what would replace Shane on the midseason schedule, and in the end the show’s airdates were just tight enough to record the same year of birth and death in the history books.

The few people still watching Shane on the last night of 1966 were greeted with that rarest of things in early episodic television: a resolution. The show’s instant lame-duck status gave Petitclerc and Blinn time to craft a finale that tied up the main characters’ storylines, perhaps only the second (after Route 66) in a prime-time dramatic series. After briefly considering Ryker as a serious romantic partner – not terribly plausible given all the mean things we’ve seen him do, but the writers have some devil’s-advocate fun making the stability he represents look tempting – Marian instead chooses Shane. Deliberately, I suspect, Petitclerc and Blinn invert the ending of the film, adopting their anti-hero into the community rather than casting him into the wilderness. This Shane does come back, or, rather, he opts not to leave at all. The series’ sweet last scene has an unnoticed Joey mouthing “wow” as he overhears Shane and Marian’s commitment to each other, then awakening his grandpa and whispering the news in the old man’s ear. It’s an unexpected shift away from the ostensible protagonists, and a fitting reprise of the subtle, off-center approach that defined this appealing little western.

Author’s note: Expanded and revised slightly in January 2024.

Obituary: Christopher Knopf (1927-2019)

February 27, 2019

When Christopher Knopf, who died on February 13 at the age of 91, turns up in the history books, it is usually a source rather than as a subject.

During a stint as a contract writer at ex-movie star Dick Powell’s significant and, today, too little-known Four Star Productions, Knopf (the k is pronounced, the f is silent) befriended with a trio of future television superstars: Sam Peckinpah, Bruce Geller, and Gene Roddenberry. He saw the truculence that would expand into full-blown insanity and addiction once Peckinpah became a prominent film director, and he watched from the sidelines as Geller and Roddenberry gave birth, respectively, to Mission: Impossible and Star Trek. Roddenberry kidnapped him once on his motorcycle, and took Knopf on a rain-slicked ride that ended with a crash, torn clothing, scraped skin. “Do you realize you may never do that again?” Roddenberry asked his dazed companion. A self-effacing family man, Knopf had little in common with these larger-than-life characters, but remained a bemused, lifelong observer of their perpetual midlife crises.

And yet Knopf’s own accomplishments, despite his reticence to claim credit for them, were prodigious. A past president of the Writers Guild of America (from 1965 to 1967), an Emmy nominee, and a winner of the coveted Writers Guild Award, Knopf was a writer of considerable skill. His voice, though distinctive, echoed off those of the other talented men he shared ideas with in his formative years. His best work espouses the compassionate liberalism one associates with Roddenberry, as well as the pessimistic, myth-busting sobriety of Peckinpah. Knopf wrote about himself a great deal, although his touch was delicate enough that the elements of autobiography might remain safely hidden without the road map Knopf provides in his engaging 2010 memoir, Will the Real Me Please Stand Up.

Sensitive about his origins as a child of privilege (and a beneficiary of Hollywood nepotism), Knopf penciled himself into most of his early scripts as a grotesque but ultimately sympathetic outsider. His first television western, “Cheyenne Express” (for The Restless Gun), centers around a weasel (Royal Dano) who back-shoots the boss of his outlaw gang and then expects the show’s hero (John Payne) to protect him from retribution. Dano’s character would be utterly despicable, except that Knopf gives him a sole redeeming quality, a devotion to feeding a stray dog that tags along behind him – Umberto D in the Old West. A traditional narrative until the final seconds, “Cheyenne Express” ends with a curious anti-climax – Dano falls out the back door of a train as the gunmen close in on him – that scans like a stranger-than-fiction historical anecdote, or a proto-Peckinpavian grace note.

Inscribing his characters with a hidden personal or political meaning became Knopf’s trick for giving early westerns and crime stories a potency often missing from other episodes of the same series. A feminist streak comes through in twinned half-hours that fashioned tough, doomed distaff versions of his autobiographical loner figure. “Heller” (for The Rifleman) and the misnamed “Ben White” (for The Rebel, with an imposing Mary Murphy as a sexy outlaw’s girl known only as T) told the stories of backwoods women – defiant, independent, but with no recourse other than self-immolating violence to combat the drunken stepfathers, Indian captors, and psychotic lovers who victimize them. “Heritage,” a Zane Grey Theater, cast Edward G. Robinson as a farmer whose neutrality during the Civil War may extend as far as turning his Confederate soldier son over to Union occupiers. “That man was my father, who I felt at the time cared more about his work than about his kids,” Knopf told me. Yet the father in “Heritage” finally redeems himself, choosing his son’s life over the barn and the crops that will be burned as punishment for his collaboration.

Widening his gaze from psychological to social injustices, Knopf sketched Eisenhower as an ineffectual sheriff on Wanted Dead or Alive and contributed a fine piece of muckraking to Target: The Corrupters. An exposé of migrant labor abuse, “Journey Into Mourning” centers around a cold-eyed portrait of a cruel and eventually homicidal foreman named Claude Ivy (Keenan Wynn). Ivy’s villainy is flamboyant and inarguable but Knopf insists upon context. Ivy presents himself as a self-made success, a former worker who grants himself the right to mistreat his workers because he clawed his way out of the same misery. Even as the laborers beg and threaten for a few cents more, Ivy grubs for his own meager share, dickering with a slightly more polished but equally callous landowner (Parley Baer). Knopf’s malevolent exploiter is just the middle man; the true evil, though name is never put to it, is capitalism. As in “Heritage,” Knopf is passionate without becoming polemic, studying all sides of a dilemma with an even gaze.

At the age of thirty, Knopf netted an Emmy nomination for “Loudmouth,” an Alcoa Theatre tour-de-force written especially for Jack Lemmon. His reward, of sorts, was an exclusive contract with Four Star, the independent company that produced Alcoa (and Zane Grey Theater). It was a mixed blessing. Knopf loved working for Dick Powell and recognized that Four Star offered writers an unusual creative latitude. However, he found that he could not protect his interests as effectively as Geller, Peckinpah, or Richard Alan Simmons, Four Star’s other star scribes. Unable to unencumber himself from Powell’s credit-grabbing lackey, Aaron Spelling, Knopf spent much of his time at Four Star toiling on pilot development and other impersonal assignments.

Four Star ended badly for everyone, starting with Powell, who died in early 1963 after a brief bout with cancer. The company collapsed and Knopf made a damaging horse-trade to escape the rubble, giving up credit and financial interest in a western he co-created, The Big Valley. Knopf, in the days following John F. Kennedy’s assassination, had written a pitch called The Cannons of San Francisco, which imagined a West Coast version of the Kennedy family that would reign over Gold Rush-era California. Powell’s successor, Tom McDermott, favored a vaguely similar ranching dynasty premise from A. I. Bezzerides that already had a network commitment, and pressured Knopf into writing the first two episodes in exchange for a release from his Four Star contract. Knopf merged his own characters into Bezzerides’s setting, and the result was The Big Valley. The “created by” credit on which ended up going to Bezzerides and producer Louis F. Edelman, who brought star Barbara Stanwyck into the show. (Bezzerides exited the show more colorfully than Knopf, in a bout of fisticuffs.)

Knopf’s two-part Big Valley pilot script forayed once again into Oedipal anxiety, contrasting the manor-born assumptions of a rancher’s legitimate sons (Richard Long and Peter Breck) with the resentment of their bastard brother (Lee Majors). Left in Knopf’s care, The Big Valley might have become an epic family serial – a novel precursor to Dallas – rather than the traditional western that lingered on ABC for four seasons as a middling epitaph for Four Star.

But letting go of the Barkley clan proved liberating for Knopf, who moved on quickly to write a pair of exceptional Dr. Kildares. “Man Is a Rock,” probably his finest episodic work, takes a hard-drinking, hard-charging salesman who resides somewhere on the Glengarry Glen Ross / Mad Men axis, and fells him with a coronary event that requires not just surgery but a lengthy recuperation. Knopf’s interest is in the difficulty of accepting illness as a life-altering event, and the idea that a man might allow himself to die simply because a change in routine represents a more tangible threat. As Franklin Gaer, the salesman who tries to make a deal with death, Walter Matthau contributes an astoundingly visceral performance, full of pain and fear – a feat all the more terrifying when one realizes that Matthau was himself only a year away from a near-fatal heart attack that would shut down production of Billy Wilder’s The Fortune Cookie for months.

Although cinephilia was not a key motif in Knopf’s work, it does play a role in both of his Dr. Kildares. The second is set within the film industry, and although “Man Is a Rock” is not, it climaxes with a scene in which Franklin Gaer delivers this drunken, despairing monologue to his frightened teenage son:

There was this picture, see, and it had this trapeze artist in it. He wasn’t a Jew or anything, but he was in this concentration camp, and he and a bunch of the others broke out, including Spencer Tracy. Anyway, the Germans get to cornering this guy, this trapeze artist, up on some roof in the middle of a German town somewhere. There he is up there, and down below are a bunch of people. They’re screaming at him to jump. And scrambling over the rooftops you’ve got all the nazis with the machine guns and everything, and they’re getting to him. Well, there’s no way out. It’s either back to prison, or jump. So, that’s what he does. He throws his arms out like that, and he shoves off in the prettiest ol’ little swan dive you ever saw in your life. One hundred feet smack right down into the pavement. You know what they did in that theater? Everybody stood up and applauded. For over a minute!

The speech is not only an unusually abstract metaphor for Gaer’s dilemma, but also another coded autobiographical reference. Although Knopf doesn’t name the film in his script, Gaer is describing a moment from The Seventh Cross, a 1944 MGM production overseen by his father, Edwin H. Knopf.

In 1967, Knopf got another western pilot on the air, and this time stayed with the project to oversee its creative development. Set in 1888, Cimarron Strip was less a western than an end-of-the-western, a weekly ninety-minute elegy for the frontier that bore the unmistakable influence of the work Knopf’s friend Sam Peckinpah had been doing at Four Star. Of the series’ twenty-three episodes, at least half a dozen centered on some larger-than-life tamer of the wilderness who was now obsolete and who would, by the story’s end, be stamped violently out of existence by encroaching civilization. Knopf’s pilot script, “The Battleground,” charted the inevitable showdown between an irredeemably savage outlaw (Telly Savalas) and his former compatriot, Jim Crown (Stuart Whitman), who is now the marshal of the Cimarron Territory and the series’ protagonist. Preston Wood’s mournful “The Last Wolf” took a sociological perspective in its examination of the wolvers, a class of rambunctious hunters whose value to the community had plummeted once they hunted the prairie wolf into extinction. William Wood’s “The Roarer” guest starred Richard Boone as a cavalry lifer so conditioned to bloodshed that, as a garrison soldier, he creates violence in a time of peace. Explicitly revisionist, Harold Swanton’s “Broken Wing” and Jack Curtis’s extraordinary “The Battle of Bloody Stones” depicted thinly-disguised versions of (respectively) Wyatt Earp and Buffalo Bill as dangerous charlatans interested in only in their own mythmaking.

Network executives were perplexed by Knopf’s unorthodox approach to the conventions of the western genre, which often meant nudging Cimarron Strip into areas of allegory (several episodes had anti-war, which is to say anti-Vietnam, undertones) or toward other genres altogether. Two particularly strong segments productively hybridized the western and the horror story. “The Beast That Walks Like a Man,” with a teleplay by Stephen Kandel and Richard Fielder, puts Marshal Crown on the trail of a possibly otherworldly prairie predator that mutilates its victims in a manner unlike any known man or beast. Some scenes, such as the one in which a hardened pioneer patriarch (Leslie Nielsen) finds his family mutilated, are terrifying, and the unexpected resolution is neither outlandish nor a cop-out. Even better is Harlan Ellison’s forgotten classic “Knife in the Darkness,” which makes the bold conceptual leap of transporting Jack the Ripper into the Old West.

It would be gratifying to hold up Cimarron Strip as an overlooked masterpiece that anticipated the magnificent spate of postmodern westerns that filmmakers like Peckinpah, Robert Altman, Arthur Penn, and others would make a few years hence. Unfortunately, only a handful of the show’s finished segments achieved as much stature as the daring, offbeat synopses that Knopf detailed in our interview would suggest. The rest became casualties of an aggressive campaign of sabotage by CBS, even after Knopf and his staff pursued a preemptive strategy of appeasement by alternating straightforward action stories with more challenging high concept narratives.

Cimarron Strip was Knopf’s final foray into episodic television for more than twenty years. One of the few rank-and-file episodic writers who transitioned wholly into longform work, Knopf crafted a number of distinguished features and television films, including the cult item A Cold Night’s Death, a two-hander about scientists (Eli Wallach and Robert Culp) cracking up in Arctic isolation. For the big screen, Knopf wrote one terrific period piece, the Depression-era rail-riding epic Emperor of the North, and two-thirds of another, the western Posse. In both cases, the subtleties of his characters and ideas were coarsened by the films’ directors (Robert Aldrich and Kirk Douglas, respectively), and yet Knopf’s innate intelligence and empathy remain in evidence in the films. He returned to television at the end of his career, co-creating and producing the Steven Bochco-esque legal drama Equal Justice in 1990.

This piece was adapted from the introduction to my 2003-2004 interview with Christopher Knopf, which will be a chapter in a forthcoming book.

Obituary: Gerry Day (1922-2013)

February 27, 2013

Her father played the organ to accompany the silent The Phantom of the Opera at Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard. She watched Howard Hughes filming miniature dogfights for Hell’s Angels in a lot behind her house. The “big sister” who showed her around campus when she started at Hollywood High was Lana Turner. Orson Welles hypnotized her in his magic act at the Hollywood Canteen. Gerry Day, native daughter of Los Angeles, child of Hollywood, and a fan who parlayed her love of the movies into a career as a radio and television writer, died on February 13 at the age of 91.

A 1944 UCLA graduate, Day got her start as a newspaper reporter, filing obits and reviewing plays for the Hollywood Citizen News. A radio writing class led to spec scripts, and Day quickly became swamped with assignments for local Los Angeles programs: The First Nighter; Skippy Hollywood Theater; Theater of Famous Players. The transition to television was natural, and Day became a regular contributor to the half-hour anthologies that tried, anemically, to ape the exciting dramatic work being done live in New York. Frank Wisbar, the expatriate German director, taught her how to write teleplays for his Fireside Theater, and then Day moved over to Ford Theater at Screen Gems, working for producer Irving Starr.

A gap in her credits during the late fifties reflects a year knocking around Europe, drifting among movie folk. Back in the States, Gerry’s mother was watching television, writing to her daughter that she’d like these new horse operas that had sprung up: Rawhide, Have Gun Will Travel, Wagon Train. Ruthy Day meant that her daughter would enjoy watching them, but of course Gerry ended up writing them instead.

A city critter who loved horses and yearned to be a rancher, Day was fated to collide with television’s glut of Westerns. In 1959 she connected with Howard Christie, the genial producer of Wagon Train, who gave her a lot of leeway to write what she wanted (and used her to doctor other scripts beyond the seven or so she’s credited on). Her other key relationship was with Richard Irving, producer of the comedic Western Laredo. Day loved doing the oaters: the light-hearted romp Here Come the Brides; The High Chaparral, with its Tucson location; Tate; Temple Houston; The Virginian; Big Valley; The Outcasts; finally, fittingly, Little House on the Prairie.

Although she specialized in Westerns, Day wrote in all genres, and notched credits on some respectable dramas: Medical Center; My Friend Tony; Judd For the Defense. Peyton Place was not a particularly agreeable experience, nor was Marcus Welby (puckishly, she took a male pseudonym, “Jon Gerald,” for her episode); but Dr. Kildare and Court Martial were treasured memories. It was for Court Martial, a forgotten military drama, that she wrote her favorite script, a euthanasia story called “Judge Them Gently.”

As for the name: It wasn’t that her parents wanted a boy. It’s that there were venerated Southern family names to be preserved, and so the little girl became Gerald Lallande Day. It fit the tomboy she grew into, even though there were draft notices from the Marines and invitations to join the Playboy Club that had to be gently declined.

Gerry lived with her parents for most of her adult life, in an old bungalow in the heart of Hollywood that – apart from the traffic blasting past the tiny lawn on busy Fairfax Avenue – hadn’t changed much since her father bought it in 1937. Gerry already had cancer when I looked her up there in 2007, although it was in remission and she was feeling peppy. When I first dropped by, Gerry was wearing a pair of white slacks that Dan Dailey had picked out for her – Dan Dailey, the song-and-dance man who died in 1978.

The reason Dan Dailey had been Gerry’s personal dresser back in the day was that for a time Gerry wrote with a partner, the actress Bethel Leslie, who was Dailey’s romantic companion toward the end of his life. Day was good at writing for women, and managed on a few shows to write parts for her favorite actresses – Barbara Stanwyck, Vera Miles, and Bethel, who starred in an African Queen knockoff that Day wrote for her on Wagon Train. Day found out that Leslie was working on a memoir, and thought she had talent. They began writing together, on shows like Bracken’s World, Matt Helm, the new Dr. Kildare and the new Perry Mason, Electra Woman and Dyna Girl, Barnaby Jones. On her trips out from New York, Leslie lived in Gerry’s studio. They would split up the work: Gerry wrote in the mornings, Bethel in the afternoons, then they meshed the work together. For two years, they were staff writers together on the daytime soap The Secret Storm. “For our sins,” said Day, who detested the executive producer so much that she wouldn’t utter his name.

Day’s love for horses led her to the track. She was an unofficial bookie for the Wagon Train clan, and eventually a part owner of a racehorse, which led her into a variety of adventures that would’ve made great subplots on David Milch’s racetrack opus Luck. A devout Catholic, Day became a Eucharistic minister in her church; she also raised foster children and supported equestrian causes. And remained ever under the spell of the movies. “The other night,” she told me during my first visit, “I stayed up late to watch Rio Grande. Talk about your romance, between John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara. That was a really good film . . . .”

David Dortort and the Restless Gun

September 19, 2010

“I’m not a gun!” snarls Vint Bonner at one point in the episode “Cheyenne Express.”

I guess he forgot the name of his own show.

The Restless Gun is another one of those fifties westerns that centers a gunslinger who’s not really a gunslinger. Gunslingers were supposed to be the bad guys and, four and a half decades before Deadwood, a bad guy couldn’t be the protagonist of a TV show. Have Gun – Will Travel and Wanted: Dead or Alive, with their fractured titles, were the important entries in this peculiar subgenre, the ones that maintained a measure of ambiguity about how heroic their heroes were. If you’ve never heard of The Restless Gun . . . well, it’s not because it doesn’t have a colon or an em-dash in the title.

The Restless Gun bobs to the top of the screener pile now because of the reactions to the obit for producer David Dortort that I tossed off last week. Several readers posted comments seconding my indifference toward Bonanza but suggesting that Dortort’s second creation, The High Chaparral, might be worth a look. I didn’t have any High Chaparrals handy, but I did have Timeless Media’s twenty-three episode volume of The Restless Gun, which Dortort produced during the two TV seasons that immediately preceded Bonanza.

The Restless Gun marked Dortort’s transition from promising screenwriter to cagey TV mogul, but I suspect Dortort was basically . . . wait for it . . . a hired gun. He didn’t create the show, he didn’t produce the pilot, and he contributed original scripts infrequently. The Restless Gun probably owes its mediocrity more to MCA, the company that “packaged” the series and produced it through its television arm Revue Productions, than to Dortort.

The pedigree of The Restless Gun is convoluted. It originated as a pilot broadcast on Schlitz Playhouse, produced by Revue staffer Richard Lewis and written by N. B. Stone, Jr. (teleplay) and Les Crutchfield (story). When The Restless Gun went to series, Stone and Crutchfield’s names were nowhere to be seen, but the end titles contained a prominent credit that read “Based on characters created by Frank Burt.” Burt’s name had gone unmentioned on the pilot. The redoubtable Boyd Magers reveals the missing piece: that The Restless Gun was actually based on a short-lived radio series called The Six Shooter, which starred James Stewart. In the pilot, the hero retained his name from radio, Britt Ponset, but in the series he became Vint Bonner. I don’t know exactly what happened between the pilot and the series, but I’ll bet that Burt wasn’t at all happy about seeing his name left off the former, and that some serious legal wrangling ensued.

(You’ll also note that Burt still didn’t end up with a pure “Created by” credit. Well into the sixties, after Revue had become Universal Television, MCA worked energetically to deprive pilot writers of creator credits and the royalties that came with them.)

The star of The Restless Gun was John Payne, whose deal with MCA made him one of the first TV stars to snag a vanity executive producer credit. Critics often tag Payne as a second-tier Dick Powell – both were song-and-dance men turned film noir heroes – but even in his noir phase Powell never had the anger and self-contempt that Payne could pull out of himself. Payne was more like a second-tier Sterling Hayden – which is not a bad thing to be. But while Payne is watchable in The Restless Gun, he’s rarely inspired.

If Payne looks mildly sedated as he wanders through The Restless Gun, it could be the scripts that put him in that state. The writing relies on familiar, calculated clichés that pander to the audience. “Thicker Than Water,” by Kenneth Gamet, guest stars Claude Akins as a card sharp whose catchphrase is, “If you’re looking for sympathy, it’s in the dictionary.” I’ll cut any script that gives Claude Akins the chance to say that line (twice!) a lot of slack. But then Akins turns out to be the absentee dad of a ten year-old boy who thinks his father is dead and . . . well, you can probably fill in the rest.

Another episode, “Man and Boy,” has Bonner trying to convince a sheriff that a wanted killer is actually the lawman’s son. Payne and Emile Meyer, playing the sheriff, step through these well-trod paces with a modest amount of conviction – and then the ending pulls a ridiculous cop-out. Dortort, he of the Cartwright dynasty, may have had a fixation on father-son relationships, but he certainly wasn’t interested in the Freudian psychology that could have given them some dramatic shading.

Dortort’s own teleplay for “The Lady and the Gun” is unusual in that it places Bonner in no physical jeopardy at all. It’s too slight to be of lasting interest, but “The Lady and the Gun,” wherein Bonner gets his heart broken by a woman (Mala Powers) who has no use for marriage, has a tricky ending and some dexterous dialogue. The low stakes and the surfeit of gunplay look ahead to Bonanza, but I’m not sure how much of the script is Dortort’s. On certain episodes, including this one, Frank Burt’s credit expands to “Based on a story and characters created by.” I’m guessing that means those episodes were rewrites of old radio scripts that Burt (who was a major contributor to Dragnet, and a good writer) penned for The Six Shooter. So what to do? It’s hard to draw a bead on Dortort as a writer because didn’t write very much, and when he did, he usually shared credit with someone else. Maybe that’s a verdict in itself.

There is one pretty good episode of The Restless Gun that illustrates how adventurous and complex the show could have been, had Dortort wanted it that way. It’s called “Cheyenne Express,” and I’m convinced its virtues are entirely attributable to the writer, Christopher Knopf. But Knopf, and his impressive body of work, are a subject I plan to tackle another time and in another format. So for now I’ll leave you to discover “Cheyenne Express” (yes, it’s in the DVD set) on your own.

An Interview With Jason Wingreen: Part Two

May 21, 2010

Last week, the character actor Jason Wingreen discussed his role as a founder of New York’s legendary off-Broadway theater, the Circle in the Square; his early film and live television roles; and his appearances on Playhouse 90, The Twilight Zone, and Wanted: Dead or Alive. As our interview continues, Wingreen recalls his work from the sixties onward.

What are some of the other TV parts you remember? You had recurring roles on a number of series.

I played in The Untouchables. I played Captain Dorset of the Chicago Police and I did seven episodes. What I remember mainly, and this is not entirely true but it seemed to be for the bulk of these seven shows, there’s a murder, and Captain Dorset arrives to investigate and look around for clues, and along comes Eliot Ness and his boys, and we greet each other and I say, “Well, Eliot, this looks like a case for you and your boys!” And with that, off I go.

Then there was The Rounders, with Chill Wills. I played the town drunk in about six episodes of that. I grew up next to a saloon, and I’ve had my fill of drunks. Then there was 12 O’Clock High, of which I did four episodes as Major Rosen, the weather officer. I was the one who’d tell the general, played by a very good actor [Robert Lansing], that we couldn’t fly, but at eight A.M. tomorrow morning I believe we will be able to get our planes in the air.

Then there was The Long Hot Summer. I played Dr. Clark, the family doctor. This was based on the feature movie, which was done with Orson Welles playing the lead. Edmond O’Brien played it on the TV series for a while. I did nine episodes, and the funny part was, when I got my first script, I looked at my role, and my character’s name was Dr. Arrod Clark. That seemed strange to me, because my dog’s vet was Arrod Clark. So I went to Frank Glicksman, who was the producer of the series, and I said, “Frank, my name here, guess what, that’s the name of my vet!” And Frank says, “I know, I know. The author of this script promised his vet that he was going to get his name on the show.”

There were a few episodes of that that are worth mentioning. One had to deal with the mother of the children of the family, who had split with the old man years ago and gone off elsewhere, but was not part of the series until this episode. They got Uta Hagen to play the role of the mother. A big star, big name. We’re in rehearsal, we’re going to shoot this particular scene of her arrival that afternoon – the introduction by the old man of her to the children. I was not in the scene, but I was certainly there to see this. I wanted to watch Uta Hagen working.

They start the rehearsal. Uta Hagen enters, and the father says, “Children, this is your mother.” And a young actor named Paul Geary says, and this was not in the script, “Mother . . . Mother . . . .” Goes up to Uta Hagen, puts his hands on her throat, and starts choking her. He had to be dragged off by the grips! He flipped out. They dragged him off and stopped shooting. They got this guy off somewhere, they sent him home. He never acted again. They had to redo it again with somebody else, I guess, but I wasn’t there. This was an actor who was high on something. They told me he was a young surfer, and wanted to be an actor, and became one. But he was on something, and “Mother, mother” is what hit him, and he went right at her.

And the funny thing about it was that when one of the producers who was on the set at the time came up to Uta Hagen to apologize for what had happened, she said, “Oh, that’s nothing. Happens to me all the time!”

The other thing about The Long Hot Summer was Eddie O’Brien, who played the role [of the patriarch] to start with, for the first seven or eight episodes. I was talking to him one day on the set. We shot it at MGM. There was a lot of stuff left over from old movies, and we were right near the entrance to the Grand Hotel from the movie Grand Hotel. So we were standing out there in the sun, just chatting, and Eddie was not happy. Not happy at all. He said to me, “They made me a lot of promises. I was going to be very big on the series. They made me promises, and it’s not working out. They’re giving all the stuff to the kids. The kids are getting all the episodes.”

I said, “Well, that’s what it is. What can you do?”

He said, “I don’t know. I don’t know, but I’m not happy.”

Anyway, one afternoon, we were shooting a scene. A man named Marc Daniels was directing. A family scene, sitting around a table, with Eddie O’Brien. They had to work on the lights before they could start to shoot. Marc Daniels says, “Let’s run the lines a little bit while we’re waiting.”

So they started, and Eddie O’Brien is mumbling, just mumbling the lines. Marc Daniels says, “Come on, Eddie, let’s make a scene out of this, you know? We’re rehearsing.”

Eddie says, “Oh, well, forget it. Let’s take a break. We’ll come back.”

O’Brien gets up and he walks to his trailer, which was right there on the set, climbs into his trailer and closes the door. We’re just hanging around, we’re waiting, we’re waiting. Then it’s, “We’re ready, let’s shoot the scene now.” So Daniels says to the second assistant, “Will you get Mr. O’Brien please? Tell him we’re ready.”

The guy starts over towards O’Brien’s trailer. The door opens. O’Brien walks out. He’s wearing his overcoat. Turns around, turns to the left, and walks to the stage door and walks out. Right in the middle of a rehearsal. That was his exit from the show! They tried to get him at home that night. He was married to Olga San Juan. She answered the phone, supposedly: “Eddie doesn’t want to talk to anybody.” He just plain quit.

We had to stop shooting, and I got called up several weeks later. They said they’re going to reshoot it, so I came back and they did it. Dan O’Herlihy was playing the father now. That’s how it is in the show business. He played it until it went off the air.

Then there were series on which you appeared many times, but never in the same role.

I did six episodes of The Fugitive, playing different characters each time. I did six Ironsides, and I did three Kojaks, directed by my friend Charlie Dubin. We met in college in 1938, and I just attended his ninety-first birthday party. I did three Bonanzas, different roles, two of them on a horse. A horse and I are not very friendly. I’m not a good man on a horse.

So westerns were not your favorite genre in which to work?

Westerns on a horse were not my favorite shows. Westerns off a horse were okay. I could play storekeepers and things like that in a western. Or a hanger-out at the saloon. I could play that very nicely. That was okay.

On series like those, would you get called back repeatedly because a casting director knew you and liked your work?

Exactly. The part would come up. They knew by this time, I had the reputation of being able to play different characters with different accents, different situations. I’m not blowing my own horn, but I was a talented actor. And easygoing. Very easy to work with. I gave nobody any trouble at all. I did what I was told, or asked to do, with a smile and a shoeshine. To quote Willy Loman.

I’d be called in for one day’s work, in one scene, and have no idea of what came before or after. And it didn’t interest me, particularly. I just concentrated on the character, and on the particular situation that that character was involved with. Small or large, or whatever it was. A line or two, or a speech or seven.

Would directors give you much attention, or leave you alone to do your thing?

They practically left me on my own. They knew who they had, the quality of my work and of my reputation, I suppose.

It’s hard to know what to ask you about all those roles where you only had a few lines.

Oh, I loved ’em. I loved being there. I enjoyed it all. I don’t mind two or three lines in just an ordinary television show. I liked to be on the set.

How would you approach a really small part, where your function was basically to deliver a piece of exposition?

I’d play the character. I’d play the character, always. I’m not worried about the plot. Plot means nothing to me in a play, because I’m not concerned with the plot, I’m concerned with the character. The character and situation will give me the clue as to how to play the part. And also, am I playing a Noo Yawk guy, you know, and I’ve got to do the accent? Or am I playing a doctor, or a professor perhaps? Or am I playing [he does the accent] a Russian? I played a Russian on Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea. With Ed Asner – Ed Asner and I and another actor, we’re Khrushchev and two of his associates, we’ve escaped from a firing squad. It wasn’t Khrushchev, but it was [based on him]. Ed Asner played the head of the Politburo, but he’s being overthrown by other members and his associates. And we end up in a riceboat. I used to kid around about us: Three Jews in a boat. And I died in the arms of Richard Basehart. [In a thick accent:] “Admiral, admiral!”

That’s not bad. Were you good at accents?

I was good at that one! Yeah, I could do an Englishman if I worked at it. Or I could play an Irishman, y’know. In Howard Beach, I lived next door to an Irish saloon. I played ball with the Irish and the Italian kids. I was the token Jew on the team. They liked me because I could play a good second base.

Did you have a good agent, who kept you working so much? You must have kept him (or her) busy.

I think I’ve probably buried all my agents, I mean literally, through the years. One was a very short young man, and he was living with an actor who played the role of Mr. Lucky on a series, John Vivyan. The second agent was a man named Leon Lantz. Leon Lantz, who was originally, I believe, from Hungary or Romania, was brought over to this country by Rudolf Schildkraut, the famous European actor who was the father of Joseph Schildkraut, the actor that became a very successful character actor here in Hollywood. Leon was recommended to me by someone. I went to meet him and he spoke with a very thick accent, and had a strange vocabulary. He said to me, “My name is Leon O. Lantz. ‘O’ for honest.” And he never got my name right.

What did he call you?

He called me “Greenspring.” It almost cost me a job once. My wife and I were living in a kind of an English castle up in the Valley, an apartment where you had to enter by walking up a staircase on the outside to get into the apartment. We had a dog, and my wife was out walking the dog. She must have been at least a good block away when the phone rang, and it was a former agent of mine. This lady called and said, “Dick Stockton at Fox called us. He thought you were still with us. He’s got a job for you in a TV show.”

I thanked her very much for the tip and I called Leon right away. I hear him call Fox on his other phone and he says, “Let me talk to Stockton.” He gets Stockton and he says, “Stockton, this is Lantz. Listen, I understand you’re looking for Greenspring.” I heard that and I started screaming into the phone. I said, “Leon, it’s Wingreen! It’s Wingreen!” And I hear him saying, “Greenspring, Greenspring.” Later my wife said she was a half a mile away and she heard me screaming.

Anyway, finally I got through to him and he made the deal. It was for a TV show. I went up to his office and I said, “For chrissake, when are you going to get my name right?” He says, “What are you complaining, you got the job, didn’t you?”

You also did some writing for television in the early sixties.

I’d always wanted to write, of course. I wanted to be a sportswriter. There was a time there when the acting tapered off. Just a short period, but I felt I had something in me that would help me when the times are bad for acting. So I rented a room in the Writers and Artists Building on Little Santa Monica. It was a small building, and underneath it was the restaurant called the Players, which had been owned at one time by Preston Sturges. Upstairs were these rooms and a couple of studios for artists. Jack Nicholson had a room there. That was way back before Jack Nicholson became the Jack Nicholson. Dan Petrie and his wife had an office there, and Mann Rubin, a lovely writer. And I set myself up there in this little office to write.

I had an idea for a thriller piece, and there was a series at Universal at the time called Thriller. Boris Karloff was the narrator who introduced each one of them. I had an idea for one of those, and I wrote out a synopsis for the whole thing, with some suggested lines of dialogue. And then I called a man at Universal that I had worked for as an actor, Doug Benton. He said, “Well, leave it with me.”

And I said, “Can I read it to you?” I didn’t want to leave it with him. I said, “I want to read it to you,” because I thought I could pep up some of those lines of dialogue, you know. Anyway, I read the whole right thing through to him. He was not the number one producer, he was the associate producer, and he said, “Well, leave it with me, and I’ll show it to Bill Frye, and I’ll get back to you.”

So the next day I had an appointment at my dentist’s. I’m in the dentist’s chair and the dentist’s nurse comes in and says, “There’s a telephone call for Mr. Wingreen.” So they bring the phone to me, and it was Doug Benton. He said, “Well, the father should be the first to know. We’re going to do it, and Bill said you’ll write the first draft.” So, the first draft became the last draft, because I wrote it and they shot it. And another writer was born.

John Newland directed it. John Newland was an actor I knew in New York in the early days. He knocked around quite a bit in New York playing very tiny roles. In fact, he was almost like an extra. He came out to Hollywood and became a very successful director, and had a show of his own, actually, One Step Beyond. He hired me once to do an acting job on one of those. Anyway, he was the director of this episode of Thriller, and I asked if I could attend. He said, “Yeah. We’ll run though it, we’ll rehease it, and then we’ll shoot it.”

Actually, what I wanted to do was get a part in it as well, but the man who was actually producing it [William Frye] said, “No, we’ve got somebody else lined up.” So I sat through their reading, and they started getting ready to shoot and John Newland said, “Well, now the writer has to leave.”

I said, “I have to leave?”

He said, “Oh, yes. We don’t want the writers to hang around and tell us to change a line or rewrite something. So you have to go now.” So that was the closest I came to seeing that in actuality until it came on the air.

I did a couple of things with other writers. I wrote an episode of The Wild Wild West, in partnership. The title of the episode was “The Night of the Torture Chamber,” and I wrote it with Phil Saltzman, who also had a room up in the Writers and Artists Building. Phil Saltzman became a pretty successful producer. Then I wrote, with another writer [Neil Nephew], who was married to Ellen Burstyn at the time, the Greatest Show on Earth episode called “The Last of the Strongmen.” The producer of that was Bob Rafelson. Then I wrote, on my own, 77 Sunset Strip and The Gallant Men at Warner Bros.

Did you like writing as much as acting?

For 77 Sunset Strip, I got the assignment and the deadline to get the first draft was in a week. At the very same time, I get an acting job on a Bonanza. On a horse. On location. I got up at six o’clock in the morning. I drove up. On these shows, they don’t pick you up, you get there. I had to drive up to Chatsworth for a seven o’clock call, to get on a horse. I do the day’s work, get back, grab a bite, out to my office, to the typewriter. For a week, both places. When I was finished with those, I was ready for a sanitarium. That was the toughest eight days I think I ever spent in my life.

The question was, which did I like better? At that time, I didn’t like either one of them! But acting was, for me, much easier. Writing did not come naturally. I wanted it to, but it didn’t. The words didn’t fall out out of me, and the ideas didn’t pour out of me, either. I struggled to get the ideas and the words. The acting, at least the words were there for me and I could do anything with them. Didn’t have to change them, didn’t have to rewrite them, didn’t have to worry about them being accepted or not.

Do you remember appearing in The Name of the Game in 1970, in an episode directed by Steven Spielberg?

Yes. I got the appointment at the producer’s office and met Spielberg there. I went there, and there’s this high school kid. I swear! I thought he was, like, seventeen years old. We talked a bit, and he said, okay, fine, we’ll let you know. And I did get the job. I think I played a professor who was kidnapped or captured in some way by bad guys. Spielberg directed it, and I had very little contact with him at all. No conversation. Little did I know what and who he’d become!

You also worked on Star Trek around the same time.

That was an episode called “The Empath.” That was just a job, that’s all. I knew John Erman, the director, well. I had worked for John on a western. I had to fall off a horse for John Erman!

Tell me how you came to play Harry the bartender during seven seasons of All in the Family and then Archie Bunker’s Place.

Paul Bogart was directing All in the Family, and the very last episode of the sixth season had a scene where Edith and Archie had an argument because he wasn’t taking her out any more, and she was going out on her own that night. So where does she go? She goes to Kelcy’s, and the story doesn’t work if she’s recognized by Kelcy. So the actor who was playing Kelcy gets the week off, and they need somebody else. And Paul was instrumental in recommending me for that role. It was just a one-shot. That’s all it was supposed to be, just that one episode. So I did it. And it was a good part, too. There was some good stuff to do in that particular episode, I assume I did it very well, because after the hiatus my agent called and said, “They want you back.”

I went back, and then I discovered that I was going to be playing that part from then on. So what happened to Kelcy? In fact, the actor who was playing Kelcy, his agent kept calling that first season, saying, “When is Bob going to be back on the show?” And unfortunately, no one in authority there had the guts to tell him that Bob’s not coming back on the show. And that’s show business.

Do you have any idea why they decided to make the change and bring you back?

Yes. I think Paul told me this, because Paul was involved in the eventual hiring of me again. I think, in that conversation about it with Carroll and Norman Lear, Carroll said, “I’m so tired of Bob’s lousy jokes.” And that was that. Apparently Bob [Hastings] was a joker at work, always coming up with jokes. And Carroll O’Connor says, “I’m tired of his lousy jokes.” And that cost the man a career, and gave me another one.

So the All in the Family role was important in your career?

Tremendous. In my career and my life, it was seven years. With increasing money each season. It allowed me to retire, let me put it that way.

Did you enjoy the show, and the role?

How could I not like it? I loved it. It was wonderful. We worked from Tuesday on to the rest of the week. Monday, you had [off], to go to the bank and the laundry. We’d arrive on Tuesday morning, we’d sit around, read the script. We’d start laughing in the morning and laugh until five o’clock, when we’d quit. I mean, how could you not like it? I’m not sure Paul loved it that much, because he had to direct. The responsibility was on him. But just as an actor in the proceedings, I had a wonderful time. With Al Melvin, and Bill Quinn, the old-timer who played the blind man.

You shared many scenes with those two, who played regular customers in Harry’s bar. Tell me what you remember about them.

Bill told me a couple of good stories during the time when we were together. Bill was a child actor, originally. He had worked with George M. Cohan when he was a child, and he was directed, as a young man, by Jed Harris in a play. Jed Harris was the man that had five shows on Broadway at one time. Apparently he was pretty tough, though. They were in rehearsal of the play, and there was a young ingenue, who was in the movie Stagecoach. Louise Platt. At one point during the rehearsal, Louise Platt was puzzled by a move or a line or something, and she said, “Jed – ” And Jed Harris said, “It’s Jed in bed. It’s Mr. Harris here.” They were later married.

So that’s one story. Another story: Bill Quinn’s daughter, Ginny, married Bob Newhart. It was a huge Hollywood wedding, in a Catholic church in Los Angeles. It was packed with top Hollywood names, big names. During the big moment when Bill Quinn leads his daughter down the aisle to give her away in marriage to Bob Newhart, as they passed a certain part of the house on their way down, there was an outburst of laughter from someone in the audience. Which certainly was not the customary thing to happen at this solemn occasion.

So after the wedding was over, there was a big reception. Everybody milling around. Bill Quinn’s there, and a friend of his, Joe Flynn, comes dashing up and says, “Oh, Billy, I’m so sorry. That was me who did that! I couldn’t help myself.”

Bill Quinn says, “What the hell! What happened?”

Joe Flynn says, “Well, I’ll tell ya. When you and Ginny started down the aisle and got past the row where we were sitting, this guy next to me said, ‘Look who they got for the father!’” That’s a wonderful line, isn’t it? That’s a Hollywood line. You’d have to be an actor to appreciate that.

I have to ask, was Allan Melvin the same in real life as he was on screen? I mean, his sort of dense Brooklyn mug persona?

He was more intelligent than that. Allan wrote little poems, little couplets of sorts, and they were very funny. Like limericks, but not quite limericks. Some of them were very intelligent and very, very funny. Never published.

Allan and I became very close friends. Allan and his wife and my wife and I would go to dinners and parties together, and we traveled together a couple of times. But Allan also was, and I hate to say this, somewhat bigoted as well. Racially. Based on what, I don’t know. His upbringing, maybe. We used to avoid those conversations, but it crept out here and there. I would say that’s probably one of his unfortunate failings. But we didn’t dwell on that.

What kind of relationship did you have with Carroll O’Connor?

A very, very close, warm relationship. And I’m sure he was preeminent in agreeing to keep me on the show. To get me on the show and stay on the show for all those years, and to have some good scripts written for me, too.

Were there episodes of All in the Family that revolved around your character?

Yes, there were a couple that did. When I was alone at the bar one night, and a young woman comes in, and she’s going to be meeting a man who never shows up. And it turns out that we go off together. And in a later scene, we come down in a bathrobe and pajamas. At least, I do. So there was that one, but mainly, of course, I was background.

I’ll tell you where I got my name. I was Harry from the beginning, but in one script, one of the writers said, “This is something where we need a second name for you. Have you got one that we could use?” Well, when I did that Broadway show, playing a soldier in Fragile Fox, I was named Snowden. And I thought, well, that guy, a typical New York guy, Snowden, after the war would go back to New York and become a bartender. So I said to the writer, “Yeah, Harry Snowden.” And then Carroll could make jokes with it. Call me Snowball. Or Snowshoes: “Hey, Snowshoes, get over here.” One of his typical malapropisms.

I was Harry Snowden, Harry the bartender, for seven years. My son, who is now a full professor at Princeton, was very funny about that. Many shows I was there with very little to say, and my son once said, when he found out what kind of money I was making: “You can make all that just for saying, ‘But, Arch . . .?’”

Later in the eighties, you appeared frequently on Matlock as a judge.

Actually, like Paul Bogart got me into All in the Family, Charlie Dubin was the one who got me into Matlock. He recommended me to the producer for the first one. It was a good one, it had some good stuff in it. Then I did eleven episodes, playing Judge Arthur Beaumont. Whenever they needed a judge that said more than “Overruled” or “Sustained,” when they had a judge who had some dialogue to deal with with Andy Griffith or anyone else, they called on me. They called me their number one judge. And then Andy took the show down to his home in North Carolina, and I was not asked to go down there. If they needed judges, they got them down there.

What was Andy Griffith like?

Well, you know how I told you that Al Melvin was somewhat bigoted? Andy Griffith was greatly bigoted.

Really?

Really. I was present when Andy Griffith was told that there was a scene they were going to do which was originally written out of the script of that episode, [featuring] Matlock’s right-hand man, who was played by a very good young black actor whose name escapes me. And Andy Griffith was given the information by one of the producer’s assistants there that the scene was going to be not eliminated, it was going to be redone, reshot, and some lines would be given back to the black actor. Griffith, very loud, not caring who was on the set at the time – they had visitors of all sorts when they were shooting – said, in a good loud voice, “Oh, sure. Okay. Go ahead, go ahead. Give it to the nigger. It’s okay. Give it to the nigger.” Does that tell you something?

That’s disappointing. I’m a big fan of Griffith’s work.

Well, it had nothing to do with his work. Do you know what I say? Do not confuse the actor with the role. I played Hitler once!

[It should be noted that Andy Griffith publicly supported Barack Obama during the 2008 presidential election. – Ed.]

I can’t close without asking about Star Wars, and the role it has played in your life.

Well, I was sent by my voice agent for a reading for Yoda [in The Empire Strikes Back]. They gave me the lines and I had to improvise an accent and a delivery of the lines, and I did, to the best of my ability. Of course, I didn’t get the job; Frank Oz got the job. But, as I learned later, they were very impressed with my reading, and there were these four lines of dialogue for Boba Fett. And as a reward to me, they offered me the role. They didn’t know Boba Fett was going to become an icon.

Then I went to record it, on a stage in Hollywood, on one afternoon in 1980. I met Gary Kurtz, the line producer, and Irvin Kershner, the director of The Empire Strikes Back. They showed me the scenes where the lines would be delivered, where Jeremy Bullock walked and spoke. I didn’t have to lip synch because he had a mask on. You could say them any time, and I fit them in. I watched it, I got a feeling of what the character was, and then we shot the stuff. I did the four lines a couple of times. Kershner came out of the control room once, made one suggestion, and I did it. And that was the day’s work. I think the actual work, aside from the hellos and goodbyes and all that, could have been no more than ten minutes.

Now, after saying goodbye, I’m leaving. Gary Kurtz was with me, walking me out. Well, sitting in the dark, in the back, in a room right near the exit, is George Lucas, whom I had not met when I came in. So Gary Kurtz introduces me to Mr. Lucas, and I said to him, “I don’t believe we’ve ever met.”

He didn’t get up; he remained seated. And he said to me the words that I still don’t know what he meant. He said, “No, but I know Boba Fett.” That was it. And then I left.

Now, I’m not imitating the sound of his voice, or even the delivery, because it wasn’t anything that I could pinpoint. It wasn’t like, “I know Boba Fett, and you’re not it.” Or, “I know Boba Fett, and you did a terrific job with it.” It wasn’t that at all. It was just, “No, but I know Boba Fett.” To this day, I don’t know what he meant.

But I do know it’s my voice on there, and I got paid. Apparently Lucas has me replaced in this latest thing that he did, in the director’s cut. Because of the continuity or something. It doesn’t mean anything to me. I don’t give a damn about what he does with the role, or doesn’t do with the role. But the thing about it is, the thing that really bothered me and everybody else who has been involved with him in these productions, is that there are no residuals. This was done on an English contract, and at that time English studios were not paying residuals. And as far as ancillary rights, Lucas tied them all up in your contract. So my voice has been used in action figures, and I have a little helmet that my son and daughter-in-law bought me on eBay and gave me as a birthday present, where if you press a little button my voice says, “Put Captain Solo in the cargo hold.” That’s my voice, and I don’t get a single penny for that. So I have no love for George Lucas.

And you also didn’t receive screen credit on The Empire Strikes Back.

No screen credit, right. So how did it come that people suddenly discovered who I was? My sister’s grandson was in a chatroom on the internet, and he happened to mention to some friends of his that his grandmother’s brother did the voice of Boba Fett. The word got around, because then I got a phone call from the editor of the [Star Wars] Insider magazine. He said, “Is it true that you did the voice of Boba Fett?” I said, “Yes, I did. That’s my voice up there. I have the contract, too.”

He said, “Can I check with the Lucas people, and then I’d like to have an interview with you for the magazine.” He did, and that’s what did it. That would have been in the year 2000. That’s what started the whole thing that’s given me this cottage industry that I’ve got here.

So these days, do you get an avalanche of Boba Fett fan mail?

An avalanche, and it doesn’t stop. Almost every day brings something. The other day, I signed a photo of Boba Fett for a little girl in Poland. It gives me something to do with my life. Otherwise I wouldn’t do very much, except existing.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Rawhide

March 12, 2010

Long-running television shows are like the proverbial elephant: they feel very different depending on where (or when, in case of a TV series) you touch one. A few, like Bonanza or C.S.I., have gone for a decade or so without changing much, but those are the exceptions. Most of the time, there are significant changes along the way in a show’s cast, producers, writers, premise, setting, tone, or budget, and these inevitably affect its quality.

I always think of Rawhide, a popular western which ran on CBS from 1959 to 1965, as the most extreme example of this phenomenon. On the surface, one episode of Rawhide looks more or less like any other. It began as the story of a cattle drive, and remained true to that concept for most of its eight seasons (actually, six and two half-seasons, since it began as a midyear replacement and closed as a midyear cancellation). The stars were Eric Fleming as the trail boss and Clint Eastwood, a sidekick who almost but not quite achieved co-lead status, as his ramrod. A few secondary cowboys came and went, but the only major cast change occurred in the last year, when Fleming was replaced by a worn-looking John Ireland.

Behind the scenes, though, the creative turnover was significant, and the types of stories that comprised Rawhide changed with each new regime. A thumbnail production history is in order.