Late Innings

September 7, 2010

John Ford directed a handful of television shows, but the most Fordian television episode I’ve ever seen is “A Head of Hair,” a Have Gun Will Travel from 1960.

Scripted by the unsung master Harry Julian Fink, “A Head of Hair” sends Paladin deep into Indian country to find a long-ago kidnapped white woman, who may or may not have been spotted from a distance by a cavalry officer (George Kennedy). The girl is blonde, but we’ll learn that hers is not the head of hair to which the title refers. As a guide, Paladin recruits a white man who used to live as a Sioux, but who is now a destitute alcoholic. The first sparse exchange between them lays out the impossibility of the mission and establishes BJ’s quiet self-contempt:

PALADIN: Would a couple of men have any chance at all?

ANDERSON: Men? A couple of Oglala Sioux, maybe. Maybe even me, seven, eight years ago. But you? They’d stake you out between two poles and flay you alive.

But Anderson takes the job because he needs drinking money. The series of tense confrontations with the Nez Perce through which he and Paladin then navigate are not standard cowboys-versus-Indians stuff. They are precise, specific rituals of masculine and tribal pride, none of which take a predictable shape. Because Paladin is a novice among the Nez Perce and Anderson is an expert, Fink has a clever device by which to clue the audience in on what’s at stake in each conflict. Gradually, these question-and-answer sessions also disclose a profound philosophical schism between the two men. Paladin is preoccupied with personal honor and ethics, while Anderson is consumed with a self-abasing nihilism. Both are deadly pragmatists, but only one of them will take the scalps of dead braves.

The Nez Perce mission concludes in victory, but it comes with a price. Success turns the two trackers against one another, for reasons that Paladin cannot understand until after violence erupts between them. “Why? Why?” are Paladin’s last words to Anderson in “A Head of Hair,” and only the answer is the unsatisfactory moral of the story of the scorpion and the frog: because it was in his nature.

Maybe it’s a coincidence that “A Head of Hair” falls chronologically between the two John Ford westerns that depict a two-man journey into the wilderness in search of a missing white woman (or women) in the custody of Indians. Both of the films imagine such captivity as a kind of unspeakable horror. “A Head of Hair” doesn’t dwell on that aspect of the story, but it does glance at the repatriated Mary Grange (Donna Brooks) long enough to construe her as lost, maybe for good, in the breach between two cultures. Another spare Fink line: “I would have gone with him,” Mary says, looking sadly after a departing Anderson. “They say the Sioux are kind to their women.”

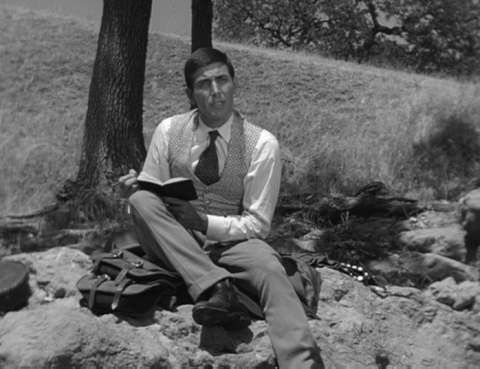

I haven’t yet identified the actor who plays Anderson because that’s the blinking neon sign that points to Ford. It is Ben Johnson, the ex-stuntman who was an important member of Ford’s “repertory company” during the late forties and early fifties. Johnson delivers what may be his finest performance prior to the Oscar-winning turn in The Last Picture Show: understated, unadorned, just barely hinting at a deep well of sadness and self-loathing. Imagine that line – “maybe even me, seven, eight years ago” – in Johnson’s voice and then picture the flicker of a weary smile that goes with it.

There’s another Ford fellow-traveler in the mix here, too: the director, Andrew V. McLaglen, was the son of Victor McLaglen, who won an Oscar for The Informer and overlapped with Ben Johnson in two of the Cavalry Trilogy films. McLaglen didn’t have Ford’s eye but he did get to shoot “A Head of Hair” on location (in Lone Pine?), and frame his actors against the landscape in a way that reminds us the wilderness is part of the story. The precision in McLaglen’s compositions match the precision in Fink’s scenario; when those three braves whose scalps are about to be up for grabs turn their backs on Paladin, there’s room to believe that maybe gunplay really has been avoided. All that’s left is something to give “A Head of Hair” some size, and that comes via Jerry Goldsmith’s sweeping brass- and woodwind-driven score. It was one of only two that Goldsmith wrote for Have Gun Will Travel.

“A Head of Hair” falls within a string of amazingly strong segments that opened Have Gun’s fourth season. There’s another Fink masterpiece, “The Shooting of Jessie May,” a four-character confrontation that ends in a really shocking explosion of violence; “Saturday Night,” a jail-cell locked-room mystery with a dark underbelly; “The Poker Fiend,” a study of degenerate gambling with an existential component and a mesmerizing, atypically internal performance from Peter Falk; and “The Calf,” a cutting allegory about a man (Denver Pyle, also a revelation) obsessed with the wire fence that marks his territory. Lighter entries like the baseball comedy “Out at the Old Ballpark” and “The Tender Gun,” with Jeanette Nolan as a crotchety female marshal under siege (Nolan, like Walter Brennan, had a with-teeth and a without-teeth performance; guess which one this is), are not as strong but they do demonstrate the impressive tonal range of Have Gun. One measure of a great television series – one which The X-Files taught me – is the extent to which it can avoid being the same show each week while still remaining, on a fundamental level, the same show each week.

*

The source of the fourth-season shot in Have Gun’s arm? A new producer and story editor, Frank Pierson and Albert Ruben, took over, and it’s not a coincidence that both were superb writers. By that time, the star of the series, Richard Boone, had seized control of it in a way that would soon be common for TV stars but that was unprecedented in 1960.

Boone got to direct a lot of episodes but, more importantly, he had approval over the story content and the behind-the-camera personnel. A snob who thought he should be doing serious acting, not westerns, Boone set out to make Have Gun as un-western a western as possible. That’s probably how Pierson and Ruben got their jobs: Boone wanted bosses (or “bosses”) who would be down with phasing out the cowboy schtick in favor of broad comedies, existential tragedies, pastiches of Verne and Shakespeare, and so on. Of course, Pierson and Ruben fell out of favor with Boone and he kicked them to the curb after a year or so . . . but that’s a story for another day.

Regime change and star ego-trips also characterized Wanted: Dead or Alive in its third and final season. Steve McQueen had always been the whole show, but by 1959, everybody knew he was destined for major stardom, including McQueen himself, who seemed to be using the final run of episodes as a laboratory in which to determine exactly which tics and slouches to incorporate into his definitive screen persona. Wanted: Dead or Alive also got a new producer for its home stretch, a man named Ed Adamson. Supposedly McQueen drove him crazy. Adamson was a prolific writer and, either to save money or time or just because McQueen was all the hassle he could take, he took the unusual step of divvying up all twenty-six of that year’s script assignments between himself and one other writer, Norman Katkov.

Katkov was one of my first oral history subjects. Since I published that piece, I’ve used this blog to weigh in on some of Katkov’s work that I hadn’t seen at the time of our interview. The most important of the shows that were unavailable to me then was Wanted: Dead or Alive. Katkov’s fourteen episodes represent his only sustained work on a series other than Ben Casey, and so I am a little disappointed not to be able to call them another set of overlooked gems. In most cases, without consulting the credits, I’d have a hard time telling which episodes are Katkov’s and which were written by Adamson, a straight-arrow action and mystery man.

Katkov managed a couple of idiosyncratic scripts, like “The Twain Shall Meet,” in which Josh Randall teams up with a fancy easterner named Arthur Pierce Madison (Michael Lipton). Madison is a journalist, which allows Katkov (a former beat reporter) to get in some knowing gags. Contrary to the usual genre expectation of the western hero’s stoic modesty, Josh is intrigued, even flattered, at the prospect of having his exploits recorded for posterity. Mary Tyler Moore has an amusing bit as a saloon girl who’s even more dazzled by the prospect of fame. Katkov focuses on the differences in how Josh and Madison make their respective livings: the contrast between physical and intellectual (and, amusingly, steady versus freelance work). In a quiet moment, Madison asks, “Is it all you want?” Josh replies, “Almost.” Westerns did not thrive on introspection, so it’s a shock to see a show like Wanted: Dead or Alive take a pause to contemplate whether its hero is happy in his work.

*

Does it seem as if this space circles back sooner or later to a small group of very good writers? I would argue that the history of television circles that way, too. Anthony Lawrence: another oral history subject on whom I’ve followed up here, first on The Outcasts and now on Hawaii Five-O. Lawrence logged one episode each in the third and fourth season, and the trademarks I described out in my profile are evident in both. There are the show-offy literary allusions: “Two Doves and Mr. Heron” ends with a quote from the Buddha. There is the interest in topical issues, which began on Five-O with the germ-warfare classic “Three Dead Cows at Makapuu” (germ warfare). Lawrence followed that up with scripts on homosexuality (Vic Morrow, fruity in more ways than one, as a whack-job who fondles John Ritter in “Two Doves”) and Vietnam (“To Kill or Be Killed”).

There is also what may be Lawrence’s defining trait as a writer: the unpredictable burst of emotional intensity within otherwise routine material. “To Kill or Be Killed” reminded me of how puzzled I was that the same Outer Limits writer could have come up with both the heart-rending “The Man Who Was Never Born” and the diffident, heavy-handed “The Children of Spider County.” In “To Kill or Be Killed,” Lawrence caps three hit-or-miss acts of family melodrama (dove son vs. hawk father) with a long, exhausting monologue – a tape-recorded suicide note that plays over horrified reaction shots of the other characters. It might seem like lazy writing, and maybe it was, to withhold all the emotion from a script and then dump it into the final minutes. But I think Lawrence was crazy like a fox. That monologue concerns My Lai (under a different name), something a lot of people watching Hawaii Five-O probably didn’t want to hear about, and with his crude structural tactic Lawrence drops the topic in their laps like a turd on the dinner table.

Hawaii Five-O, in its fourth year, is almost exactly the same show as it was in its first. It’s still a show that allows for a lot of variety in its formula – or rather, the alternation between six or eight different formulas. Unlike on Wanted: Dead or Alive, one can detect an individual authorial touch in many of the episodes. The lurid pulp shocker “Beautiful Screamer” is pure Stephen Kandel. The dullest espionage outings and the most heavy-handed McGarrett lectures usually trace back to the team of Jerry Ludwig and Eric Bercovici, who, unfortunately, wrote quite a few of each.

One of the most popular Five-Os, “Over Fifty? Steal,” falls into this stretch of the series. It was penned by a writer new to the show, E. Arthur Kean. It’s a semi-comedy in the cuddly-oldster-as-criminal-mastermind genre, featuring a smug Hume Cronyn as a serial robber who goes out of his way to taunt McGarrett and crew. I like “Over Fifty,” but Kean’s second script for the series deserves more attention. More diamond-hard than heart-shaped, “Ten Thousand Diamonds and a Heart” is another caper, but played deadly straight this time. It starts with a parking garage prison bust and turns into a jewel heist, which Kean sets up as a battle of wits between another master criminal (Tim O’Connor) and an impregnable high-rise. Kean fusses over the details: scale models, elevator schematics, medication for a bum ticker. Somehow, he makes the minutiae fascinating. They’re the diamonds, and the heart is the clash between O’Connor and the “banker” (the guy who’s funding the heist) played by Paul Stewart. It’s a portrait of two paranoid career criminals who can’t trust anyone but themselves, gnashing at each other until they tear their own caper apart.

I had seen a few of Kean’s earlier scripts, for The Fugitive and The F.B.I., without having much of a reaction. But the Hawaii Five-Os that mark him down as, in the Sarrisian lexicon, a Subject For Further Research.

*

Also this year I’ve watched most of the fourth and penultimate season of NBC’s Dr. Kildare, a once near-great doctor drama that slowly turned mushy and bland. Further research department: one of those turkeys marked the prime-time debut, as far as I can tell, of one E. Arthur Kean.

A few fourth-year episodes written by series veterans like Jerry McNeely and Archie L. Tegland still felt the old Dr. Kildare: tough, smart, sagacious. Tegland’s “A Reverence For Life” trots out one of the standbys of the medical drama, a story of a patient who refuses life-saving treatment due to her religious convictions. My own inclinations always favor science over superstition; but Dennis Weaver, with his innate humility, is so perfect as the Jehovah’s Witness whose wife is dying that I was rooting for him to prevail in his faith.

I am also partial to Christopher Knopf’s “Man Is a Rock,” a terrifying study of a heart attack victim (Walter Matthau) forced to confront his own mortality, and “Maybe Love Will Save My Apartment House,” a zany romp by Boris Sobelman, who wrote a handful of very funny black comedies for Thriller and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour. But Kildare’s fourth year includes duds from other good writers, like Adrian Spies (Saints and Sinners) and Jack Curtis (Ben Casey), and that’s often a sign of tinkering from upstairs.

By 1964 Richard Chamberlain was one of TV’s hottest stars, a heartthrob with a viable recording career. MGM (which produced Dr. Kildare) had cashed in on his popularity by building three medium-budget feature films around him in three years. Both the studio and the network had a big investment in Chamberlain, and I’m guessing that executive producer Norman Felton may have capitulated to pressure to give viewers a maximum dose of Chamberlain romancing and singing. I’m not kidding about the singing: “Music Hath Charms” is a plotless let’s-put-on-a-show show about an amateur night for the hospital staff. I can’t decide which episode is the series’ nadir: “A Journey to Sunrise,” a vanity piece that gives Raymond Massey (who co-starred as Kildare’s windbag boss Dr. Gillespie) a dual role as a dying Hemingway-esque writer, or “Rome Will Never Leave You,” a prophetically titled, turtle-paced three-parter that contrives gooey romances for both Kildare and Gillespie during an Italian business trip.

I’ve proposed corporate greed as the major cause for the de-fanging of the once sharp Dr. Kildare, but there’s also the David Victor factor. In the years before signing on as Norman Felton’s right-hand man, Victor was a hack genre writer (with a partner, Herbert Little, Jr., who disappeared after Victor hit the big time). In the years after he and Felton parted ways, Victor copied the Kildare format and quickly ran it into comfortable mediocrity as the head man on Marcus Welby. Was Victor the source of the blandness that set in on Kildare as the show’s exec, Norman Felton (by all accounts a discerning producer), turned his attention to developing The Lieutenant and The Man From U.N.C.L.E. Maybe he was just in the wrong place at the wrong time – but if so, Victor was in an even wronger place at an even wronger time a year later, when he moved over to The Man From U.N.C.L.E. as the supervising producer who supervised that show’s second- and third-season slide into cringeworthy camp.

*

The Man From U.N.C.L.E.: When we last checked in on TV’s favorite spies, we found a mortified Robert Vaughn frugging with a man in a gorilla suit. I had hoped to follow that cheap shot with a report on how The Man From U.N.C.L.E. rebounded in its final half-season, as new producer Anthony Spinner followed the network’s oops-we-fucked-up orders to take out the yuks and put back the action. I’d heard that the fourth season was “too grim,” but hey, I like grim. Especially if it’s the alternative to Solo and Kuryakin partying with Sonny and Cher or riding on stinkbombs (funny for Kubrick, not for Kuryakin). Grim is good.

Didn’t work out that way. The fourth season isn’t grim, it’s dull. The plots are perfunctory, the characters cardboard, the casting uninspired. The books say that Spinner tried to bring U.N.C.L.E. back to its roots, but the shows play like nobody much cared what went on the screen. I gave up when I got to “The THRUSH Roulette Affair,” which rien ne va pluses with one of the laziest deus ex machinas I’ve ever seen. See, THRUSH baddie is torturing some guy with a machine that figures out the victim’s worst fear and then gets him to talk in a room full of (not at all scary) footage of said fear. In this case, the poor sucker is more afraid of being run over by a train. Wouldn’t you know it, when the shit hits the fan, the evil scientist bursts out with a clumsy load of exposition: turns out he tested the machine on the main THRUSH baddie (Michael Rennie), and his greatest fear is exactly the same as the other guy’s. Two trainophobes in a row! Which means that when the U.N.C.L.E. guys shove Rennie into the scaring-to-death machine, all of that (not at all scary) train stock footage is already cued up!

Usually I don’t even notice plot holes but, seriously, this one’s just insulting. How could Spinner or the writer (Arthur Weingarten) or the story editor (Irv Pearlberg) not come up with anything better than that? Especially since they swiped the idea from 1984 in the first place?

Another of the fourth season U.N.C.L.E.s spieled some boring Latin American palace intrigue (featuring not-at-all-Latin American Madlyn Rhue), which got me to thinking. The Lieutenant ended by sending its stateside serviceman hero off to die in Vietnam. U.N.C.L.E. should’ve gone out the same way, with Solo and Kuryakin headed off to Chile to assassinate Salvador Allende. That would’ve been my kind of grim.

Leftovers

January 14, 2008

I’ve decided to treat the articles on my website as finished pieces and resist the temptation to rewrite or add onto them as new information comes my way. But that doesn’t preclude annotating them occasionally by way of this blog.

I was pleased to note that the best segment by far of the batch of The Outcasts that I watched over the holidays was written by Anthony Lawrence. That confirmed my view of Lawrence as an adept commercial TV writer capable of occasionally going deeper with a poignant, heartfelt work, like his masterpiece, The Outer Limits‘ “The Man Who Was Never Born.” The Outcasts, in case you’ve never heard of it, was an odd biracial western that ran on ABC for one season (1968-1969). It never quite made it as an allegory for Black Panther-era racial politics, but it did offer TV’s first black male action hero who didn’t take any crap from anybody, and it depicted the shaky camaraderie between buddy protagonists who were a former slave (Otis Young) and slavemaster (Don Murray) with a surprising integrity.

Lawrence’s “Take Your Lover in the Ring” was a romance between Young’s character and another ex-slave (Gloria Foster), a woman who appears to be traveling in servitude to her former master (John Dehner, ideally cast), even though it’s a few years after the Civil War. The series’ pilot included a good throwaway line about how former slave Young had once been the stakes in a poker game, and I could see how Lawrence picked up on that notion and spun it into “Take Your Lover”‘s initial premise of Young winning Foster’s freedom at a card table. Of course, it’s a starcrossed love affair – for Lawrence, there was no other kind – once the script pulls a big switcheroo and reveals that Foster and Dehner are actually partners in a con game. (The title of the segment refers to an obscure bit of African American folklore, a elaborate children’s chant that Lawrence fearlessly incorporates into Young and Foster’s dialogue as a kind of courtship ritual. It’s almost too purple, but I think it works.)

“Take Your Lover in the Ring” was the Outcasts episode submitted for Emmy consideration (Hugo Montenegro’s score got a nomination) and the Museum of TV and Radio screened it in a 1993 program, so I’m not the only one who found it memorable. Lawrence’s other Outcasts segment, “The Glory Wagon,” was more in keeping with the show’s emphasis on uncomplicated action fare. But I enjoyed being able to peg it as a Lawrence script even before his credit came on screen, because Jack Elam’s flamboyant outlaw is introduced in the prologue as “Abel Morgan Blackner.” It’s yet another variation on a similarly named character, plucked from his wife’s family history, whom Lawrence incorporated over and over again in his work. Sussing out the personal within the generally impersonal medium of mainstream television is the kind of task that historians haven’t even begun to come to terms with. Individual instances like this one might seem trivial, but I think they add up to an important consideration when one tries to sort out how content was forged out of the variety of influences (cultural, financial, political, individual) at work in the TV industry.

I wrote about Norman Katkov‘s “The Lonely Hostage” as one of his best efforts. But until now I had never taken a look at the other two Ironsides that Katkov wrote, because he shared credit on them with other writers. “Perfect Crime” is a campus sniper whodunit with a magnificently implausible resolution, but Katkov’s teleplay is tricky enough to keep the viewer guessing along with the cop characters. “Side Pocket,” on which Katkov was probably the last of the three credited writers (Sy Salkowitz and the talented Charles A. McDaniel were the others), is slightly better, a pool hustling story centered around a restrained performance by Jack Albertson as Manie (or is that “Money”? I can’t tell from the actors’ pronunciations) Howard, a legendary, calculating pool shark who “doesn’t play for less than $500.”

It’s foolhardy to speculate on who wrote what in these split-credit teleplays, but I’d wager (less than $500, though) that Katkov was responsible for most of Albertson’s spare dialogue: “The hand, the stick, they eye. It’s like they got a life of their own. They do what they want. It’s like I’m not even there. Just the hand, the stick, and the eye.” The first two seasons of Ironside, recently out on DVD, include all of these episodes (there’s another Katkov credit in the third season, which will hopefully appear soon). If you’re only sampling the show via online rentals or the like, these three are well worth including.

Finally, it was a treat to find some video of Don M. Mankiewicz on Youtube, in which he mostly discusses labor issues but also catalogs some of the same high points of a TV career that he told me about in our interview. So far it’s the only positive dividend I can think of to come out of the devastating writer’s strike of ought-seven.