Obituary: Gerry Day (1922-2013)

February 27, 2013

Her father played the organ to accompany the silent The Phantom of the Opera at Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard. She watched Howard Hughes filming miniature dogfights for Hell’s Angels in a lot behind her house. The “big sister” who showed her around campus when she started at Hollywood High was Lana Turner. Orson Welles hypnotized her in his magic act at the Hollywood Canteen. Gerry Day, native daughter of Los Angeles, child of Hollywood, and a fan who parlayed her love of the movies into a career as a radio and television writer, died on February 13 at the age of 91.

A 1944 UCLA graduate, Day got her start as a newspaper reporter, filing obits and reviewing plays for the Hollywood Citizen News. A radio writing class led to spec scripts, and Day quickly became swamped with assignments for local Los Angeles programs: The First Nighter; Skippy Hollywood Theater; Theater of Famous Players. The transition to television was natural, and Day became a regular contributor to the half-hour anthologies that tried, anemically, to ape the exciting dramatic work being done live in New York. Frank Wisbar, the expatriate German director, taught her how to write teleplays for his Fireside Theater, and then Day moved over to Ford Theater at Screen Gems, working for producer Irving Starr.

A gap in her credits during the late fifties reflects a year knocking around Europe, drifting among movie folk. Back in the States, Gerry’s mother was watching television, writing to her daughter that she’d like these new horse operas that had sprung up: Rawhide, Have Gun Will Travel, Wagon Train. Ruthy Day meant that her daughter would enjoy watching them, but of course Gerry ended up writing them instead.

A city critter who loved horses and yearned to be a rancher, Day was fated to collide with television’s glut of Westerns. In 1959 she connected with Howard Christie, the genial producer of Wagon Train, who gave her a lot of leeway to write what she wanted (and used her to doctor other scripts beyond the seven or so she’s credited on). Her other key relationship was with Richard Irving, producer of the comedic Western Laredo. Day loved doing the oaters: the light-hearted romp Here Come the Brides; The High Chaparral, with its Tucson location; Tate; Temple Houston; The Virginian; Big Valley; The Outcasts; finally, fittingly, Little House on the Prairie.

Although she specialized in Westerns, Day wrote in all genres, and notched credits on some respectable dramas: Medical Center; My Friend Tony; Judd For the Defense. Peyton Place was not a particularly agreeable experience, nor was Marcus Welby (puckishly, she took a male pseudonym, “Jon Gerald,” for her episode); but Dr. Kildare and Court Martial were treasured memories. It was for Court Martial, a forgotten military drama, that she wrote her favorite script, a euthanasia story called “Judge Them Gently.”

As for the name: It wasn’t that her parents wanted a boy. It’s that there were venerated Southern family names to be preserved, and so the little girl became Gerald Lallande Day. It fit the tomboy she grew into, even though there were draft notices from the Marines and invitations to join the Playboy Club that had to be gently declined.

Gerry lived with her parents for most of her adult life, in an old bungalow in the heart of Hollywood that – apart from the traffic blasting past the tiny lawn on busy Fairfax Avenue – hadn’t changed much since her father bought it in 1937. Gerry already had cancer when I looked her up there in 2007, although it was in remission and she was feeling peppy. When I first dropped by, Gerry was wearing a pair of white slacks that Dan Dailey had picked out for her – Dan Dailey, the song-and-dance man who died in 1978.

The reason Dan Dailey had been Gerry’s personal dresser back in the day was that for a time Gerry wrote with a partner, the actress Bethel Leslie, who was Dailey’s romantic companion toward the end of his life. Day was good at writing for women, and managed on a few shows to write parts for her favorite actresses – Barbara Stanwyck, Vera Miles, and Bethel, who starred in an African Queen knockoff that Day wrote for her on Wagon Train. Day found out that Leslie was working on a memoir, and thought she had talent. They began writing together, on shows like Bracken’s World, Matt Helm, the new Dr. Kildare and the new Perry Mason, Electra Woman and Dyna Girl, Barnaby Jones. On her trips out from New York, Leslie lived in Gerry’s studio. They would split up the work: Gerry wrote in the mornings, Bethel in the afternoons, then they meshed the work together. For two years, they were staff writers together on the daytime soap The Secret Storm. “For our sins,” said Day, who detested the executive producer so much that she wouldn’t utter his name.

Day’s love for horses led her to the track. She was an unofficial bookie for the Wagon Train clan, and eventually a part owner of a racehorse, which led her into a variety of adventures that would’ve made great subplots on David Milch’s racetrack opus Luck. A devout Catholic, Day became a Eucharistic minister in her church; she also raised foster children and supported equestrian causes. And remained ever under the spell of the movies. “The other night,” she told me during my first visit, “I stayed up late to watch Rio Grande. Talk about your romance, between John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara. That was a really good film . . . .”

Back in the Saddle

October 17, 2012

Lined up on the shelves of the library where I work are a number of television Westerns from Timeless Media, discs that I haven’t purchased (yet) and that Netflix doesn’t carry. Recently I got around to taking home a stack of episodes from the first through the third seasons of Wagon Train, where I still have a lot of gaps.

Everything I’ve written about Wagon Train so far has been pretty critical. I was mixed on the rejuvenated seventh season, which expanded to ninety minutes and went to color, and I also mocked the laziness of some of the episodes immediately preceding that change. But a random survey of a dozen or so early segments reveals a better, cannier show. Wagon Train doesn’t rank among the best television Westerns, but it can fill up an oppressive August weekend quite effectively. What better actor to turn to than Ward Bond, with his grating, unmodulated donkey-bellow, to make himself heard over the full blast of my air conditioner?

Wagon Train started with a premise that was extremely well-designed, as simple and sturdy as a Conestoga. It had two lead characters, Major Seth Adams (Ward Bond) and Flint McCullough (Robert Horton), each of whom could serve as the center of a story or step into the background whenever the guest star of the week took up most of the screen time. That was important, because most Wagon Trains introduced a guest character in the very title (“The Joe Schmidlapp Story”), and the show was marketed on the basis of its big-name guest stars.

(This was a promise Wagon Train could deliver upon, initially, because it was produced by MCA, which until 1959 was also the biggest talent agency in town. It’s doubtful that Shelley Winters or Ernest Borgnine, both at the peak of their film careers in 1957, would have deigned to appear in a television Western – a brand new one, no less – without a little arm-twisting by Lew Wasserman or his dark-suited lieutenants. After MCA was forced to sell its agency business, Wagon Train’s guest stars became slightly less stellar, although they still comprised the top actors working in television.)

Adams and McCullough were modular leading men, versatile moving parts that could be plugged into a variety of different places. If Adams remained tethered to the train, McCullough, a scout who rode ahead looking for trouble, could roam about and stumble into adventures of almost any sort. Most dual-lead Westerns had interchangeable characters – the stage drivers of Stagecoach West, the rest stop minders of Laramie – but Wagon Train was conceived from the start to alternate between “home” and “away” stories.

Think about what a useful blueprint that is, from every point of view. The writers could tell almost any kind of Western story they could think of, without being constrained by the trail setting or the cumbersome pack of settlers in the train. The two stars could minimize their screen time and avoid the fatigue that plagued actors who carried a whole show on their backs (although that didn’t spare Ward Bond a fatal heart attack in 1960). Shooting on multiple episodes could overlap if necessary. And the audience was treated to a much greater variety of faces and settings than on a typical weekly series.

The Flint McCullough episodes remind me of the “off-campus” event episodes that serial dramas would try decades later. The West Wing and ER, especially, liked to send a main character – John Carter (Noah Wyle) or C. J. Cregg (Allison Janney) – off on his or her own once per season, to solve a personal problem or star in an action set-piece. It was Emmy-bait (Janney’s one-off with Donald Moffat as her ailing father is still one of my favorite television hours) but, more importantly, gave the audience a break from the intricate and potentially exhausting multi-character storylines. Wagon Train has the capacity to loosen up in the same way: just when I start to get tired of watching Ward Bond scream at the idiot settlers who wreak havoc on his train, there’s a breather where the smooth, likable Horton breezes through a less predictable adventure in a less familiar setting.

Wagon Train and ER might seem like apples and oranges, but in fact the Western series was one of the earliest dramas to take some tentative steps toward serialization. Most seasons began with an episode or two set in St. Louis, at the beginning of the train, and ended with one or two segments set at the end of the trail, in San Francisco. For instance, the third season opens with an episode (“The Stagecoach Story”) detailing the main characters’ return trip, by stage, from the West Coast to Missouri, following the preceding years’ train. The next episode (“The Greenhorn Story,” with the inevitable Mickey Rooney in the title role) covers the formation of the new train, with an emphasis on the naïve easterners’ adjustment to a new, harder way of life.

In the middle of the season, episodes do not follow a chronology – some of them span the course of months, and the physical progress from one to the next would probably zigzag back and forth across a map – but the viewer is not discouraged from thinking of each season’s various progatonists as members of the same train, with every individual story one panel in a mosaic of headaches thrust upon Major Adams over the course of a single year. The first season finale, “The Sacramento Story,” makes this assumption explicit; it is a combined sequel to three earlier episodes. (The series would continue to “check in” with popular characters, bringing Borgnine back in the second season premiere to reprise his role from the pilot, “The Willy Moran Story,” and revisiting the young lovers from “The Heather and Hamish Story” a year later in “The Last Circle Up” – albeit with both roles recast.) Since Wagon Train was never truly serialized, I tend to view its unusual commitment to beginning and ending at opposite ends of the trail as less about continuity than variety. In other words, it was an excuse to plant a few episodes in an urban setting instead of amid the monotonous plains.

In its willingness to make each episode as different from the others as the format would bear, Wagon Train became porous enough to allow for auteurism, among both its writers and directors. I mentioned few of these cases the last time I wrote about Wagon Train, and I’m still uncovering more of them. What to make of Jean Holloway, who wrote both the dull “Stagecoach Story” and the lively, appealing “Greenhorn Story”? Somewhere in the middle, in terms of quality, falls “The C. L. Harding Story,” a “haircut” of Lysistrata in which a muckraking reporter (Claire Trevor) leads the women of the train in a general strike. It’s tempting to read something into the fact that this very safe excursion into pre-feminism comes from the pen of one of the show’s two regular women writers, and probably much too cheap. Sometimes the absence of a strong voice is itself revealing: “The Cappy Darrin Story,” with Ed Wynn as a sea captain who takes the term “prairie schooner” a bit too literally, was written by Stanley Kallis, a veteran production man who penned only a handful of scripts. There’s an incongruous fantasy sequence, in which Cappy and his young grandson (Tommy Nolan) fight off some pirates, that rouses journeyman director Virgil W. Vogel from his slumber to try his hand at some dutch angles (even more incongruous in the world of Wagon Train). These dead ends take me back to the Western’s long-standing showrunner, Howard Christie, who seems to have favored the rather cloying tone – light at heart but somehow leaden – that “The Cappy Darrin Story” shares with many other segments.

Then there’s “The Ruth Owens Story,” one of two early episodes directed by the great Robert Florey (Murders in the Rue Morgue; The Beast With Five Fingers). This one is set mostly at night and includes many bold close-ups of actors, often in profile, framed against total blackness. Its expressionistic imagery – the frame grabs assembled below illustrate only a few of the Florey’s bold compositions – doesn’t resemble any other Wagon Train I’ve seen or, indeed any other television episode this side of The Twilight Zone.

David Dortort and the Restless Gun

September 19, 2010

“I’m not a gun!” snarls Vint Bonner at one point in the episode “Cheyenne Express.”

I guess he forgot the name of his own show.

The Restless Gun is another one of those fifties westerns that centers a gunslinger who’s not really a gunslinger. Gunslingers were supposed to be the bad guys and, four and a half decades before Deadwood, a bad guy couldn’t be the protagonist of a TV show. Have Gun – Will Travel and Wanted: Dead or Alive, with their fractured titles, were the important entries in this peculiar subgenre, the ones that maintained a measure of ambiguity about how heroic their heroes were. If you’ve never heard of The Restless Gun . . . well, it’s not because it doesn’t have a colon or an em-dash in the title.

The Restless Gun bobs to the top of the screener pile now because of the reactions to the obit for producer David Dortort that I tossed off last week. Several readers posted comments seconding my indifference toward Bonanza but suggesting that Dortort’s second creation, The High Chaparral, might be worth a look. I didn’t have any High Chaparrals handy, but I did have Timeless Media’s twenty-three episode volume of The Restless Gun, which Dortort produced during the two TV seasons that immediately preceded Bonanza.

The Restless Gun marked Dortort’s transition from promising screenwriter to cagey TV mogul, but I suspect Dortort was basically . . . wait for it . . . a hired gun. He didn’t create the show, he didn’t produce the pilot, and he contributed original scripts infrequently. The Restless Gun probably owes its mediocrity more to MCA, the company that “packaged” the series and produced it through its television arm Revue Productions, than to Dortort.

The pedigree of The Restless Gun is convoluted. It originated as a pilot broadcast on Schlitz Playhouse, produced by Revue staffer Richard Lewis and written by N. B. Stone, Jr. (teleplay) and Les Crutchfield (story). When The Restless Gun went to series, Stone and Crutchfield’s names were nowhere to be seen, but the end titles contained a prominent credit that read “Based on characters created by Frank Burt.” Burt’s name had gone unmentioned on the pilot. The redoubtable Boyd Magers reveals the missing piece: that The Restless Gun was actually based on a short-lived radio series called The Six Shooter, which starred James Stewart. In the pilot, the hero retained his name from radio, Britt Ponset, but in the series he became Vint Bonner. I don’t know exactly what happened between the pilot and the series, but I’ll bet that Burt wasn’t at all happy about seeing his name left off the former, and that some serious legal wrangling ensued.

(You’ll also note that Burt still didn’t end up with a pure “Created by” credit. Well into the sixties, after Revue had become Universal Television, MCA worked energetically to deprive pilot writers of creator credits and the royalties that came with them.)

The star of The Restless Gun was John Payne, whose deal with MCA made him one of the first TV stars to snag a vanity executive producer credit. Critics often tag Payne as a second-tier Dick Powell – both were song-and-dance men turned film noir heroes – but even in his noir phase Powell never had the anger and self-contempt that Payne could pull out of himself. Payne was more like a second-tier Sterling Hayden – which is not a bad thing to be. But while Payne is watchable in The Restless Gun, he’s rarely inspired.

If Payne looks mildly sedated as he wanders through The Restless Gun, it could be the scripts that put him in that state. The writing relies on familiar, calculated clichés that pander to the audience. “Thicker Than Water,” by Kenneth Gamet, guest stars Claude Akins as a card sharp whose catchphrase is, “If you’re looking for sympathy, it’s in the dictionary.” I’ll cut any script that gives Claude Akins the chance to say that line (twice!) a lot of slack. But then Akins turns out to be the absentee dad of a ten year-old boy who thinks his father is dead and . . . well, you can probably fill in the rest.

Another episode, “Man and Boy,” has Bonner trying to convince a sheriff that a wanted killer is actually the lawman’s son. Payne and Emile Meyer, playing the sheriff, step through these well-trod paces with a modest amount of conviction – and then the ending pulls a ridiculous cop-out. Dortort, he of the Cartwright dynasty, may have had a fixation on father-son relationships, but he certainly wasn’t interested in the Freudian psychology that could have given them some dramatic shading.

Dortort’s own teleplay for “The Lady and the Gun” is unusual in that it places Bonner in no physical jeopardy at all. It’s too slight to be of lasting interest, but “The Lady and the Gun,” wherein Bonner gets his heart broken by a woman (Mala Powers) who has no use for marriage, has a tricky ending and some dexterous dialogue. The low stakes and the surfeit of gunplay look ahead to Bonanza, but I’m not sure how much of the script is Dortort’s. On certain episodes, including this one, Frank Burt’s credit expands to “Based on a story and characters created by.” I’m guessing that means those episodes were rewrites of old radio scripts that Burt (who was a major contributor to Dragnet, and a good writer) penned for The Six Shooter. So what to do? It’s hard to draw a bead on Dortort as a writer because didn’t write very much, and when he did, he usually shared credit with someone else. Maybe that’s a verdict in itself.

There is one pretty good episode of The Restless Gun that illustrates how adventurous and complex the show could have been, had Dortort wanted it that way. It’s called “Cheyenne Express,” and I’m convinced its virtues are entirely attributable to the writer, Christopher Knopf. But Knopf, and his impressive body of work, are a subject I plan to tackle another time and in another format. So for now I’ll leave you to discover “Cheyenne Express” (yes, it’s in the DVD set) on your own.

Late Innings

September 7, 2010

John Ford directed a handful of television shows, but the most Fordian television episode I’ve ever seen is “A Head of Hair,” a Have Gun Will Travel from 1960.

Scripted by the unsung master Harry Julian Fink, “A Head of Hair” sends Paladin deep into Indian country to find a long-ago kidnapped white woman, who may or may not have been spotted from a distance by a cavalry officer (George Kennedy). The girl is blonde, but we’ll learn that hers is not the head of hair to which the title refers. As a guide, Paladin recruits a white man who used to live as a Sioux, but who is now a destitute alcoholic. The first sparse exchange between them lays out the impossibility of the mission and establishes BJ’s quiet self-contempt:

PALADIN: Would a couple of men have any chance at all?

ANDERSON: Men? A couple of Oglala Sioux, maybe. Maybe even me, seven, eight years ago. But you? They’d stake you out between two poles and flay you alive.

But Anderson takes the job because he needs drinking money. The series of tense confrontations with the Nez Perce through which he and Paladin then navigate are not standard cowboys-versus-Indians stuff. They are precise, specific rituals of masculine and tribal pride, none of which take a predictable shape. Because Paladin is a novice among the Nez Perce and Anderson is an expert, Fink has a clever device by which to clue the audience in on what’s at stake in each conflict. Gradually, these question-and-answer sessions also disclose a profound philosophical schism between the two men. Paladin is preoccupied with personal honor and ethics, while Anderson is consumed with a self-abasing nihilism. Both are deadly pragmatists, but only one of them will take the scalps of dead braves.

The Nez Perce mission concludes in victory, but it comes with a price. Success turns the two trackers against one another, for reasons that Paladin cannot understand until after violence erupts between them. “Why? Why?” are Paladin’s last words to Anderson in “A Head of Hair,” and only the answer is the unsatisfactory moral of the story of the scorpion and the frog: because it was in his nature.

Maybe it’s a coincidence that “A Head of Hair” falls chronologically between the two John Ford westerns that depict a two-man journey into the wilderness in search of a missing white woman (or women) in the custody of Indians. Both of the films imagine such captivity as a kind of unspeakable horror. “A Head of Hair” doesn’t dwell on that aspect of the story, but it does glance at the repatriated Mary Grange (Donna Brooks) long enough to construe her as lost, maybe for good, in the breach between two cultures. Another spare Fink line: “I would have gone with him,” Mary says, looking sadly after a departing Anderson. “They say the Sioux are kind to their women.”

I haven’t yet identified the actor who plays Anderson because that’s the blinking neon sign that points to Ford. It is Ben Johnson, the ex-stuntman who was an important member of Ford’s “repertory company” during the late forties and early fifties. Johnson delivers what may be his finest performance prior to the Oscar-winning turn in The Last Picture Show: understated, unadorned, just barely hinting at a deep well of sadness and self-loathing. Imagine that line – “maybe even me, seven, eight years ago” – in Johnson’s voice and then picture the flicker of a weary smile that goes with it.

There’s another Ford fellow-traveler in the mix here, too: the director, Andrew V. McLaglen, was the son of Victor McLaglen, who won an Oscar for The Informer and overlapped with Ben Johnson in two of the Cavalry Trilogy films. McLaglen didn’t have Ford’s eye but he did get to shoot “A Head of Hair” on location (in Lone Pine?), and frame his actors against the landscape in a way that reminds us the wilderness is part of the story. The precision in McLaglen’s compositions match the precision in Fink’s scenario; when those three braves whose scalps are about to be up for grabs turn their backs on Paladin, there’s room to believe that maybe gunplay really has been avoided. All that’s left is something to give “A Head of Hair” some size, and that comes via Jerry Goldsmith’s sweeping brass- and woodwind-driven score. It was one of only two that Goldsmith wrote for Have Gun Will Travel.

“A Head of Hair” falls within a string of amazingly strong segments that opened Have Gun’s fourth season. There’s another Fink masterpiece, “The Shooting of Jessie May,” a four-character confrontation that ends in a really shocking explosion of violence; “Saturday Night,” a jail-cell locked-room mystery with a dark underbelly; “The Poker Fiend,” a study of degenerate gambling with an existential component and a mesmerizing, atypically internal performance from Peter Falk; and “The Calf,” a cutting allegory about a man (Denver Pyle, also a revelation) obsessed with the wire fence that marks his territory. Lighter entries like the baseball comedy “Out at the Old Ballpark” and “The Tender Gun,” with Jeanette Nolan as a crotchety female marshal under siege (Nolan, like Walter Brennan, had a with-teeth and a without-teeth performance; guess which one this is), are not as strong but they do demonstrate the impressive tonal range of Have Gun. One measure of a great television series – one which The X-Files taught me – is the extent to which it can avoid being the same show each week while still remaining, on a fundamental level, the same show each week.

*

The source of the fourth-season shot in Have Gun’s arm? A new producer and story editor, Frank Pierson and Albert Ruben, took over, and it’s not a coincidence that both were superb writers. By that time, the star of the series, Richard Boone, had seized control of it in a way that would soon be common for TV stars but that was unprecedented in 1960.

Boone got to direct a lot of episodes but, more importantly, he had approval over the story content and the behind-the-camera personnel. A snob who thought he should be doing serious acting, not westerns, Boone set out to make Have Gun as un-western a western as possible. That’s probably how Pierson and Ruben got their jobs: Boone wanted bosses (or “bosses”) who would be down with phasing out the cowboy schtick in favor of broad comedies, existential tragedies, pastiches of Verne and Shakespeare, and so on. Of course, Pierson and Ruben fell out of favor with Boone and he kicked them to the curb after a year or so . . . but that’s a story for another day.

Regime change and star ego-trips also characterized Wanted: Dead or Alive in its third and final season. Steve McQueen had always been the whole show, but by 1959, everybody knew he was destined for major stardom, including McQueen himself, who seemed to be using the final run of episodes as a laboratory in which to determine exactly which tics and slouches to incorporate into his definitive screen persona. Wanted: Dead or Alive also got a new producer for its home stretch, a man named Ed Adamson. Supposedly McQueen drove him crazy. Adamson was a prolific writer and, either to save money or time or just because McQueen was all the hassle he could take, he took the unusual step of divvying up all twenty-six of that year’s script assignments between himself and one other writer, Norman Katkov.

Katkov was one of my first oral history subjects. Since I published that piece, I’ve used this blog to weigh in on some of Katkov’s work that I hadn’t seen at the time of our interview. The most important of the shows that were unavailable to me then was Wanted: Dead or Alive. Katkov’s fourteen episodes represent his only sustained work on a series other than Ben Casey, and so I am a little disappointed not to be able to call them another set of overlooked gems. In most cases, without consulting the credits, I’d have a hard time telling which episodes are Katkov’s and which were written by Adamson, a straight-arrow action and mystery man.

Katkov managed a couple of idiosyncratic scripts, like “The Twain Shall Meet,” in which Josh Randall teams up with a fancy easterner named Arthur Pierce Madison (Michael Lipton). Madison is a journalist, which allows Katkov (a former beat reporter) to get in some knowing gags. Contrary to the usual genre expectation of the western hero’s stoic modesty, Josh is intrigued, even flattered, at the prospect of having his exploits recorded for posterity. Mary Tyler Moore has an amusing bit as a saloon girl who’s even more dazzled by the prospect of fame. Katkov focuses on the differences in how Josh and Madison make their respective livings: the contrast between physical and intellectual (and, amusingly, steady versus freelance work). In a quiet moment, Madison asks, “Is it all you want?” Josh replies, “Almost.” Westerns did not thrive on introspection, so it’s a shock to see a show like Wanted: Dead or Alive take a pause to contemplate whether its hero is happy in his work.

*

Does it seem as if this space circles back sooner or later to a small group of very good writers? I would argue that the history of television circles that way, too. Anthony Lawrence: another oral history subject on whom I’ve followed up here, first on The Outcasts and now on Hawaii Five-O. Lawrence logged one episode each in the third and fourth season, and the trademarks I described out in my profile are evident in both. There are the show-offy literary allusions: “Two Doves and Mr. Heron” ends with a quote from the Buddha. There is the interest in topical issues, which began on Five-O with the germ-warfare classic “Three Dead Cows at Makapuu” (germ warfare). Lawrence followed that up with scripts on homosexuality (Vic Morrow, fruity in more ways than one, as a whack-job who fondles John Ritter in “Two Doves”) and Vietnam (“To Kill or Be Killed”).

There is also what may be Lawrence’s defining trait as a writer: the unpredictable burst of emotional intensity within otherwise routine material. “To Kill or Be Killed” reminded me of how puzzled I was that the same Outer Limits writer could have come up with both the heart-rending “The Man Who Was Never Born” and the diffident, heavy-handed “The Children of Spider County.” In “To Kill or Be Killed,” Lawrence caps three hit-or-miss acts of family melodrama (dove son vs. hawk father) with a long, exhausting monologue – a tape-recorded suicide note that plays over horrified reaction shots of the other characters. It might seem like lazy writing, and maybe it was, to withhold all the emotion from a script and then dump it into the final minutes. But I think Lawrence was crazy like a fox. That monologue concerns My Lai (under a different name), something a lot of people watching Hawaii Five-O probably didn’t want to hear about, and with his crude structural tactic Lawrence drops the topic in their laps like a turd on the dinner table.

Hawaii Five-O, in its fourth year, is almost exactly the same show as it was in its first. It’s still a show that allows for a lot of variety in its formula – or rather, the alternation between six or eight different formulas. Unlike on Wanted: Dead or Alive, one can detect an individual authorial touch in many of the episodes. The lurid pulp shocker “Beautiful Screamer” is pure Stephen Kandel. The dullest espionage outings and the most heavy-handed McGarrett lectures usually trace back to the team of Jerry Ludwig and Eric Bercovici, who, unfortunately, wrote quite a few of each.

One of the most popular Five-Os, “Over Fifty? Steal,” falls into this stretch of the series. It was penned by a writer new to the show, E. Arthur Kean. It’s a semi-comedy in the cuddly-oldster-as-criminal-mastermind genre, featuring a smug Hume Cronyn as a serial robber who goes out of his way to taunt McGarrett and crew. I like “Over Fifty,” but Kean’s second script for the series deserves more attention. More diamond-hard than heart-shaped, “Ten Thousand Diamonds and a Heart” is another caper, but played deadly straight this time. It starts with a parking garage prison bust and turns into a jewel heist, which Kean sets up as a battle of wits between another master criminal (Tim O’Connor) and an impregnable high-rise. Kean fusses over the details: scale models, elevator schematics, medication for a bum ticker. Somehow, he makes the minutiae fascinating. They’re the diamonds, and the heart is the clash between O’Connor and the “banker” (the guy who’s funding the heist) played by Paul Stewart. It’s a portrait of two paranoid career criminals who can’t trust anyone but themselves, gnashing at each other until they tear their own caper apart.

I had seen a few of Kean’s earlier scripts, for The Fugitive and The F.B.I., without having much of a reaction. But the Hawaii Five-Os that mark him down as, in the Sarrisian lexicon, a Subject For Further Research.

*

Also this year I’ve watched most of the fourth and penultimate season of NBC’s Dr. Kildare, a once near-great doctor drama that slowly turned mushy and bland. Further research department: one of those turkeys marked the prime-time debut, as far as I can tell, of one E. Arthur Kean.

A few fourth-year episodes written by series veterans like Jerry McNeely and Archie L. Tegland still felt the old Dr. Kildare: tough, smart, sagacious. Tegland’s “A Reverence For Life” trots out one of the standbys of the medical drama, a story of a patient who refuses life-saving treatment due to her religious convictions. My own inclinations always favor science over superstition; but Dennis Weaver, with his innate humility, is so perfect as the Jehovah’s Witness whose wife is dying that I was rooting for him to prevail in his faith.

I am also partial to Christopher Knopf’s “Man Is a Rock,” a terrifying study of a heart attack victim (Walter Matthau) forced to confront his own mortality, and “Maybe Love Will Save My Apartment House,” a zany romp by Boris Sobelman, who wrote a handful of very funny black comedies for Thriller and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour. But Kildare’s fourth year includes duds from other good writers, like Adrian Spies (Saints and Sinners) and Jack Curtis (Ben Casey), and that’s often a sign of tinkering from upstairs.

By 1964 Richard Chamberlain was one of TV’s hottest stars, a heartthrob with a viable recording career. MGM (which produced Dr. Kildare) had cashed in on his popularity by building three medium-budget feature films around him in three years. Both the studio and the network had a big investment in Chamberlain, and I’m guessing that executive producer Norman Felton may have capitulated to pressure to give viewers a maximum dose of Chamberlain romancing and singing. I’m not kidding about the singing: “Music Hath Charms” is a plotless let’s-put-on-a-show show about an amateur night for the hospital staff. I can’t decide which episode is the series’ nadir: “A Journey to Sunrise,” a vanity piece that gives Raymond Massey (who co-starred as Kildare’s windbag boss Dr. Gillespie) a dual role as a dying Hemingway-esque writer, or “Rome Will Never Leave You,” a prophetically titled, turtle-paced three-parter that contrives gooey romances for both Kildare and Gillespie during an Italian business trip.

I’ve proposed corporate greed as the major cause for the de-fanging of the once sharp Dr. Kildare, but there’s also the David Victor factor. In the years before signing on as Norman Felton’s right-hand man, Victor was a hack genre writer (with a partner, Herbert Little, Jr., who disappeared after Victor hit the big time). In the years after he and Felton parted ways, Victor copied the Kildare format and quickly ran it into comfortable mediocrity as the head man on Marcus Welby. Was Victor the source of the blandness that set in on Kildare as the show’s exec, Norman Felton (by all accounts a discerning producer), turned his attention to developing The Lieutenant and The Man From U.N.C.L.E. Maybe he was just in the wrong place at the wrong time – but if so, Victor was in an even wronger place at an even wronger time a year later, when he moved over to The Man From U.N.C.L.E. as the supervising producer who supervised that show’s second- and third-season slide into cringeworthy camp.

*

The Man From U.N.C.L.E.: When we last checked in on TV’s favorite spies, we found a mortified Robert Vaughn frugging with a man in a gorilla suit. I had hoped to follow that cheap shot with a report on how The Man From U.N.C.L.E. rebounded in its final half-season, as new producer Anthony Spinner followed the network’s oops-we-fucked-up orders to take out the yuks and put back the action. I’d heard that the fourth season was “too grim,” but hey, I like grim. Especially if it’s the alternative to Solo and Kuryakin partying with Sonny and Cher or riding on stinkbombs (funny for Kubrick, not for Kuryakin). Grim is good.

Didn’t work out that way. The fourth season isn’t grim, it’s dull. The plots are perfunctory, the characters cardboard, the casting uninspired. The books say that Spinner tried to bring U.N.C.L.E. back to its roots, but the shows play like nobody much cared what went on the screen. I gave up when I got to “The THRUSH Roulette Affair,” which rien ne va pluses with one of the laziest deus ex machinas I’ve ever seen. See, THRUSH baddie is torturing some guy with a machine that figures out the victim’s worst fear and then gets him to talk in a room full of (not at all scary) footage of said fear. In this case, the poor sucker is more afraid of being run over by a train. Wouldn’t you know it, when the shit hits the fan, the evil scientist bursts out with a clumsy load of exposition: turns out he tested the machine on the main THRUSH baddie (Michael Rennie), and his greatest fear is exactly the same as the other guy’s. Two trainophobes in a row! Which means that when the U.N.C.L.E. guys shove Rennie into the scaring-to-death machine, all of that (not at all scary) train stock footage is already cued up!

Usually I don’t even notice plot holes but, seriously, this one’s just insulting. How could Spinner or the writer (Arthur Weingarten) or the story editor (Irv Pearlberg) not come up with anything better than that? Especially since they swiped the idea from 1984 in the first place?

Another of the fourth season U.N.C.L.E.s spieled some boring Latin American palace intrigue (featuring not-at-all-Latin American Madlyn Rhue), which got me to thinking. The Lieutenant ended by sending its stateside serviceman hero off to die in Vietnam. U.N.C.L.E. should’ve gone out the same way, with Solo and Kuryakin headed off to Chile to assassinate Salvador Allende. That would’ve been my kind of grim.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Rawhide

March 12, 2010

Long-running television shows are like the proverbial elephant: they feel very different depending on where (or when, in case of a TV series) you touch one. A few, like Bonanza or C.S.I., have gone for a decade or so without changing much, but those are the exceptions. Most of the time, there are significant changes along the way in a show’s cast, producers, writers, premise, setting, tone, or budget, and these inevitably affect its quality.

I always think of Rawhide, a popular western which ran on CBS from 1959 to 1965, as the most extreme example of this phenomenon. On the surface, one episode of Rawhide looks more or less like any other. It began as the story of a cattle drive, and remained true to that concept for most of its eight seasons (actually, six and two half-seasons, since it began as a midyear replacement and closed as a midyear cancellation). The stars were Eric Fleming as the trail boss and Clint Eastwood, a sidekick who almost but not quite achieved co-lead status, as his ramrod. A few secondary cowboys came and went, but the only major cast change occurred in the last year, when Fleming was replaced by a worn-looking John Ireland.

Behind the scenes, though, the creative turnover was significant, and the types of stories that comprised Rawhide changed with each new regime. A thumbnail production history is in order.

The creator of Rawhide was Charles Marquis Warren, a writer and director of B movie westerns who had played a significant role in transitioning the radio hit Gunsmoke to television in 1955. Warren stayed with Rawhide for its first three years (longer than he had remained on Gunsmoke, or would last on his next big TV hit, The Virginian). For the fourth season, CBS elevated Rawhide’s story editor, Hungarian-born screenwriter Endre Bohem, to the producer’s chair. Vincent M. Fennelly, a journeyman who had produced Trackdown and Stagecoach West, took over for the fifth and sixth seasons. During the seventh year, the team of Bruce Geller and Bernard L. Kowalski succeeded Fennelly, only to be fired in December and replaced by a returning Endre Bohem. A final team, comprising executive producer Ben Brady and producer Robert E. Thompson, couldn’t save Rawhide from cancellation halfway through its eighth season.

Most Rawhide fans will tell you that the early seasons are the best. I can guess why they think that, but I believe they’re wrong. Warren’s version of Rawhide played it safe, telling traditional western stories with predictable resolutions. The writers were second-rate, and Warren padded their thin plots with endless shots of migrating “beeves.” Warren was content to deploy totemic western tropes – Indian attacks, evil land barons, Confederate recidivists – in the same familiar ways that the movies had used them for decades.

During the Bohem and Fennelly years, things began to improve. Both producers brought in talented young writers, including Charles Larson and future Star Trek producer Gene L. Coon, who contributed quirky anecdotes like “The Little Fishes” (Burgess Meredith as a dreamer transplanting a barrel of fragile Maine shad fry to the Sacramento River) and pocket-sized epics like the amazing “Incident of the Dogfaces” (James Whitmore as a malevolent but terrifyingly effective cavalry sergeant). There were still episodes that coasted on routine genre action, but they alternated with meaty, character-driven pieces.

When Kowalski and Geller (the eventual creators of Mission: Impossible) took over Rawhide in 1964, they pulled off a daring experiment that has never been matched in the history of television. The new producers upended Rawhide, dismantling western myths and muddying genre barriers with surgical precision and undisguised glee. Geller and Kowalski commissioned teleplays like “Corporal Dasovik,” a Vietnam allegory which portrayed the cavalry as slovenly, dishonorable, and homicidal, and “The Meeting,” a surreal clash between the drovers and a prototypical mafia on a weirdly barren plain. The two-part “Damon’s Road” was a rowdy shaggy-dog comedy, complete with infectious Geller-penned showtunes (“Ten Tiny Toes”) and a subplot that reduces Fleming’s square-jawedhero to buffoonery, pushing a railroad handcar across the prairie in his longjohns.

Geller and Kowalski’s Rawhide segments may be the finest television westerns ever made. Taken as a whole, they represent a comprehensive rebuke to the myth of the Old West. They anticipate the brutal, disillusioned revisionist western films made by Sam Peckinpah and others in the following decade. Peckinpah’s The Westerner (1959) and Rod Serling’s The Loner (1965-1966) touch upon some of the same ideas, but they do not take them as far. Not until Deadwood, forty years later, did television produce another western that looked, felt, and smelled like the seventh season of Rawhide.

The only problem with the Geller-Kowalski Rawhide, which the producers undoubtedly understood, was that it had little to do with the Rawhide that had come before. Many observers just didn’t get it, including Eric Fleming, who refused to perform some of the material. (Eastwood, apparently, got the idea, and Geller and Kowalski shifted their attention from Fleming’s character to his.) Another non-believer was William S. Paley, the president of CBS, who was aghast at what had been done to one of his favorite programs. Paley fired Geller, Kowalski, and their story editor Del Reisman midseason in what they termed “the Christmas Eve Massacre.” Paley uttered one of television history’s most infamous quotes when he ordered their replacements to “put the cows back in.”

During the final year of Rawhide, the new producers did just that. The series attracted some talented young directors and actors, including Raymond St. Jacques as TV’s first black cowboy. But no one took any chances in the storytelling.

*

Critics don’t have much value if they neglect to interrogate their own assumptions, question their long-held opinions. Which explains why I’ve been slogging through the first and second season of Rawhide, screening the episodes I hadn’t seen before and looking for glimmers of life that I might have missed. Most of the segments I watched in this go-round proved to be just as handsomely mounted, and fatally tedious, as the rest. But one episode, “Incident of the Blue Fire,” triggered some doubts about my dismissal of Charles Marquis Warren, and led me to write this piece.

“Incident of the Blue Fire” (originally broadcast on December 11, 1959) is a little masterpiece about a cowhand named Lucky Markley, who believes he’s a jinx and whose frequent mishaps gradually convince the superstitious drovers that he’s right. It sounds like one of those dead-end cliches that I listed in my description of the Warren era above. But the writer, John Dunkel, and Warren, who directed, get so many details just right that “Incident of the Blue Fire” dazzled me with its authenticity, its rich atmosphere, and its moving, ironic denouement.

Dunkel’s script gives the herders a problem that is specific to their situation, rather than TV western-generic. They’re moving across the plains during a spell of weather so humid that the constant heat lightning threatens to stampede the cattle. The drovers swap stories about earlier stampedes, trying to separate truth from legend, to find out if any of them have actually seen one. Eastwood’s character, Rowdy Yates, averts a stampede just before it begins, and explains to his boss how he spotted the one skittish animal. Favor, the trail boss, replies that Rowdy should have shot the troublemaker as soon as he recognized it. These cowboys are professional men, discussing problems and solutions in technical terms, like doctors or lawyers in a medical or legal drama.

Then Lucky appears, asking to join the drive with thirty-odd mavericks that he has rounded up. “Those scrawny, slab-sided, no-good scrub cows?” Favor asks. Not unkindly, he dispels Lucky’s illusions about the value of his cattle. Lucky shrugs it off, and negotiates to tag along with Favor’s herd to the next town. Then Favor and one of his aides debate the merits of allowing a stranger to join them. In one brief, matter-of-fact scene, Dunkel introduces viewers to an unfamiliar way of making a living in the west and to a type of man who might undertake it.

Warren directs this unpretentious material with casual confidence. He gets a nuanced performance from Skip Homeier, whose Lucky is proud and quick to take offense, but also smart and eager to ingratiate himself with others. Warren’s pacing is measured, but it’s appropriate to a story of men waiting for something to happen. Tension mounts palpably in scenes of men doing nothing more than sitting around the campfire, uttering Dunkel’s flavorful lines:

WISHBONE: Somethin’ about them clouds hangin’ low. And the heat. Sultry-like. It’s depressin’, for animals and men.

COWHAND: Yep, it’s the kind of weather old Tom Farnsworth just up and took his gun, shot hisself, and nobody knowed why.

“Incident of the Blue Fire” features some unusually poetic lighting and compositions. Much of it was shot day-for-night, outdoors, and the high-key imagery creates, visually, the quality of stillness in the air that the cattlemen remark upon throughout the show. (The cinematographer was John M. Nickolaus, Jr., who went on to shoot The Outer Limits, alternating with Conrad Hall.) There’s an eerie beauty to many of the images, like this simple close-up of Eric Fleming framed against the sky.

Does one terrific episode alter my take on the early Rawhide years? No – they’re still largely a bore. But now I can concede that Charles Marquis Warren was probably after something worthwhile, a quotidian idea of the old west as a place of routine work and minor incident. That the series lapsed into drudgery much of the time, that the stories usually turned melodramatic at all the wrong moments, can be lain at the feet of a mediocre writing pool. Or, perhaps, Warren capitulated too willingly to the network’s ideas of where and how action had to fit into a western. But Rawhide had a great notion at its core, and that explains how the show could flourish into brilliance when later producers, better writers, were given enough room to make something out of it.

How I Spent My Summer Vacation

October 10, 2008

After a somewhat longer summer hiatus than planned, I’m back with some notes on a few recent early television discoveries. By now there aren’t too many TV shows from the fifties or sixties with which I’m totally unfamiliar, but until last year’s complete DVD release of the series, Man with a Camera (1958-60) fell into that category. This was one of the few half-hour action series of the late fifties of which (to my knowledge) no episodes had circulated among private libraries, and I suspect many TV enthusiasts were curious about it for two reasons. First, it starred Charles Bronson, long before Bronson became the movies’ oldest action hero; and second, for us hard-core TV wonks, it was the show that the talented producer Buck Houghton was running immediately before he moved to MGM to oversee the first three seasons of The Twilight Zone. Houghton was a line producer, not a writer, so one doesn’t expect to find any kind of thematic or stylistic connection, but this modest little low-budget effort was assembled with the same care that make the grander MGM-backlot fantasies of The Twilight Zone so visually compelling.

Bronson always struck me as the unlikeliest of stars, and Man with a Camera is something of a case study in how his frozen visage and monotone voice can produce a kind of anti-charismatic charisma. Whatever his deficiencies as an actor, Bronson had confidence, and he’s surprisingly loose when the opportunity presents himself. In “The Bride,” for instance, Kovic briefly poses as a naïve, heavily-accented immigrant negotiating a mail-order marriage, and the fun that Bronson has with this goofy scene is contagious.

Based on the little I had read, I wasn’t sure exactly what form Man with a Camera would take. Newspaper drama? International adventure? It turns out to be a de facto detective drama, one of those shows in which people with no business fighting crime nevertheless do so. Johnny Staccato, a Greenwich Village nightclub owner/unlicensed private dick, was a contemporaneous figure, and they still crop up on TV now and then – Hack (2002-2004) starred David Morse as a Philadelphia cab driver who doubled as a vigilante for hire. These series make one wonder: why not just make a show about actual private eyes (or cops), instead of burdening the writers with the chore of explaining every week how a photographer or a restaurateur got himself into this mess?

In the case of Man with a Camera, the first dozen or so episodes tell plausible, if cliched, stories consistent with actual photojournalism, at least if you grant that Kovic is the rush-off-to-battle-zone macho-adventurer type of photojournalist. Kovic tries to snap a shot of an Appalachia-style gangsters’ summit (“The Big Squeeze”), gets accused of doctoring a pic of a bigwig politician (“Turntable”), and exposes crimes while covering a boxing match (“Second Avenue Assassin”) and the testing of a new military plane (“Another Barrier”).

Over time, the number of actual photographers credited as technical advisors dwindled from three to one, and later scripts barely attempted to justify why Kovic was investigating Mexican drug smuggling (“Missing”) or bodyguarding an arrogant movie star in Cannes (“Kangaroo Court”). “But there’s a picture angle!” insists a client as he begs Kovic to investigate a blackmail ring preying on adopted children in “Girl in the Dark.” Thanks for the reminder.

A little more often than most fifties crime dramas, Man with a Camera varied the standard mystery-plus-fisticuffs equation. The most unusual episode, the lynch mob story “Six Faces of Satan,” is essentially The Twilight Zone‘s “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street” minus the science fiction angle. The earnest script, by David P. Harmon, is as subtle as a brick against the back of the head, but director Boris Sagal stages it with a claustrophobic fervor that never allows the tension to subside. It’s all tight angles, angry faces shoved into the lens, crowds converging and dispersing as the camera probes the tiny interior New York street set.

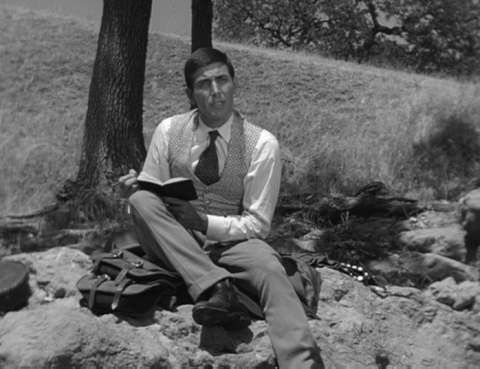

The milder pleasures of “Hot Ice Cream,” an amusement park murder story, chiefly stem from the oddball pairing of guest stars Yvonne Craig (delightful as a precocious teenaged camera buff) and Lawrence Tierney, the latter’s bald dome, if not his surly disposition, concealed by a jaunty ice cream vendor’s cap. And speaking of guest stars, does anyone recognize this actor, who makes a very early, and uncredited, appearance in the episode “The Bride”:

*

If Man with a Camera stands out as an above average example of the sort of undemanding escapism that was becoming the bread and butter of late-fifties network TV, then Tate (1960), the entire run of which has also been disgorged on DVD in a single chunk, is a more exciting kind of revelation: a serious, important, and unjustly forgotten western.

Tate was created and story-edited by Harry Julian Fink, a talented writer who probably received a deal for his own series on the strength of a number of thoughtful Have Gun Will Travel episodes. Fink’s show is a western which confronts directly the one aspect of the generally very adult Have Gun that was gussied up a little for television: the hero’s profession. Have Gun‘s Paladin sought and carried out assignments that made use of his skill with a firearm, but in practice the show was never as mercenary as its title. The tone of the stories varied from grim to frothy, and Paladin (and the series’ writers) took pride in concocting intricate, non-violent forms of conflict resolution. Tate, on the other hand, is simply and bluntly a hired killer, something about which he has no illusions and makes no apologies. He doesn’t live in an ornate San Francisco hotel suite or savor expensive cigars. Tate is dusty and beat-down and often wears a serape to conceal his handicap, a useless left arm that he keeps holstered in a mean-looking, elbow-length leather glove.

The first episode, “Home Town,” is a near-perfect examination of masculine stoicism and obligation. In it Tate returns to the town of his birth to help his mentor, an aging marshal (Royal Dano), protect a prisoner from a lynch mob. It’s a futile endeavor, of course, in the sense that the unrepentant murderer will likely hang anyway, and that’s the point. Fink seems to challenge himself to convey Tate’s backstory as unsentimentally as possible. Here’s an exchange that includes the only explanation we ever get for Tate’s dead arm:

MARSHAL: How long’s it been?

TATE: Ten years.

MARSHAL: The war and then some. Where’d it happen?

TATE: Vicksburg. I didn’t run fast enough, Morty.

MARSHAL: You’re home, son. What do you think of it?

TATE: The same. A little smaller, a little dirtier. Just a memory, Morty, it doesn’t exist any more.

Tate’s wife is buried in the same town, and again Fink conveys this element of the character’s psychological makeup obliquely. There’s a lovely scene between Tate and a waitress (Sandra Knight) who turns out to be his wife’s cousin. They discuss the girl’s resemblance to Mary Tate, but Tate never tells her that Mary was his wife. All the emotion remains unspoken. The scene ends with an iris into the cousin’s face: a technique from the silent cinema so powerful that, by 1960, it was often used ironically. But here it’s perfect, a way of releasing the pent-up sadness of the moment through form instead of dialogue.

“Stopover,” the second, and perhaps best, episode, is even more avant-garde. Fink, who wrote the script, underlines a local law officer’s disgust when Tate rides into town with a corpse across his saddle. While the sheriff executes some bureaucratic maneuvers to delay the payment of the bounty, Tate cools his heels in a saloon where he runs smack into a twitchy punk who wants to test his gun against him. It’s a familiar setup, but Fink fills it with unexpected ideas: an emphasis on money (the bounty is $2,080, and Tate insists on the $80); the extreme lengths to which Tate goes to avoid a gun duel that won’t yield a profit; the lack of ambiguity concerning a saloon girl’s actual profession (she charges five dollars to bring the guests an “extra blanket”). Smith, the young gunslinger, is not just an analogue to the modern juvenile delinquents of the fifties (a common notion in films like Nicholas Ray’s The True Story of Jesse James and Arthur Penn’s The Left-Handed Gun). He’s quite clearly a psychopath in a clinical sense. Fink makes this point mainly through the young man’s speech, which is fanciful to the point of incomprehensibility. At one point, he refers to man Tate has killed as “a magical person,” an anachronistic, New Age-y phrase that startles one into thinking of Smith more in terms of Manson worship than of western villainy.

Indeed, “Stopover” is about language, or the failure of communication. Tate and the young gun talk past each other throughout their encounter: the gunman wants to know who he’s challenging, but Tate won’t tell him his name, while Tate keeps probing to find out the relationship between Smith and the dead man. He can’t wrap his mind around the idea that there might not be any connection between them – that violence can occur without a rational motive.

Television westerns were, of course, plentiful in the extreme during the fifties and sixties, a fact that necessitated as much differentiation as possible. A wide range of generic traditions and storytelling approaches characterize the major TV westerns: The Virginian told sweeping, epic tales which emphasized the vastness of the effort to settle the frontier; Wagon Train was a dramatic anthology in disguise, eschewing western naturalism in favor of character-driven stories; The Rifleman was a bildungsroman that reduced the west to a canvas for illustrating life lessons; and so on.

I think the most productive model for the TV western, the one best suited to the limitations of the small screen, was the sort of spare, unsentimental ultra-minimalism that characterizes Budd Boetticher’s and some of Anthony Mann’s film westerns. The two key series in this mode were Sam Peckinpah’s quirky The Westerner and Rod Serling’s blatantly existential The Loner. Tate belongs within this tradition, although it’s not quite at the same level as those two masterworks.

One problem is David McLean, who plays Tate (“Just Tate,” incidentally, the missing first name a midpoint marker on the way to Eastwood’s Man with No Name). McLean has the right world-weary look and gruff voice for the role – he was later famous as a cowboy-styled cigarette pitchman. But his performance lacks depth; as the series progresses it becomes evident that McLean is cycling through the same four or five line readings, and the guest stars nudge him off the screen. (It doesn’t help McLean that Tate‘s uncredited but canny casting director paired him with an unusual number of future stars: Louise Fletcher, Martin Landau, Robert Culp, James Coburn, Warren Oates, and, in small but showy roles in two episodes, Robert Redford.)

But the primary failure of Tate was a lack of sustainability. Unlike Rod Serling on The Twilight Zone or Stirling Silliphant on Route 66, Harry Julian Fink fumbled the critical step of finding gifted, complementary voices to fill in the gaps between his own contributions. The six Tates written by Fink, all but one of them gems, and the seven episodes penned by lesser writers might as well be from two wholly different series. By the last episode, Gerry Day’s “The Return of Jessica Jackson,” there’s a lamentable scene in which Tate pulls out a Bible and proselytizes to the distraught heroine. This Tate is a far more conventional TV hero than the Tate of the pilot, a terse pragmatist of uncertain morality, adrift on a sea of grief and regret.

Not that it mattered much: Tate ran as a replacement series in the summer of 1960, meaning that NBC had likely abandoned any plans for renewing it even before the series debuted. Just like The Westerner and The Loner, both of which were short-lived, Tate was too cerebral and too downbeat for the mainstream.

(A brief note for the Corrections Department: One frustrating bit of misinformation which has proliferated across the internet, even on the official page for the Tate DVD, is that the series was videotaped. In fact, the quickest glimpse at any Tate episode reveals that it was shot on film, not with the clunky video cameras of the era, which were limited in both resolution and range of motion. I’m not sure how that idea got started, except perhaps that the show carries an onscreen copyright in the name of Roncom Video Films – Perry Como’s production company. But the term “video,” at that time, was an industry synonym for television.)

*

At the other end of the scale is Laredo (1965-1967), which lives down to its reputation as one of the least distinguished of nineteen-sixties westerns. In fact, it’s one of the worst TV shows, period, and perhaps a minor benchmark in the dumbing down of the medium.

Laredo concerns the adventures of three rowdy Texas rangers, played by Neville Brand, Peter Brown, and William Smith. (Philip Carey, cashing a paycheck, delivers a scene’s worth of exposition in each episode and then disappears, just as Rick Jason had taken to doing in the later years of Combat.) It’s distinguished from the glut of other westerns of its time mainly by its strident efforts to maintain a would-be comedic tone. Mainly, this means that, in the midst of carrying out the usual lawman’s duties of leading posses and fighting Indians, the heroes incessantly needle and play elaborate pranks upon one another. It’s the first, but by no means the last, TV show I can think of in which adults behave like hyperactive pre-teens for no discernible reason – except, perhaps, kinship with a target demographic.

What’s startling about Laredo is how cruel and violent its prank subplots are. In the first episode, for example, Reese Bennett (Brand) retaliates against the other two rangers for their earlier mockery by leaving them bound in an Indian camp, where they’re later tortured. In that instance, Reese gets the upper hand, but in most episodes Cooper (Brown) and Riley (Smith) outfox him. Brand’s performance makes this dynamic extremely uncomfortable. I can imagine that Brand was trying to create a Paul Bunyanesque caricature – a Texan who was so dumb that he, et cetera, et cetera. But Reese is so helplessly stupid, and his chums are so smug and superior, that the experience is akin to watching schoolyard bullies taunt a retarded child. Laredo unavoidably implicates the viewer in its peculiar brand of cruelty – never is civility imposed on any of the characters – and I, for one, didn’t feel like playing. Perhaps I’ve just lost my capacity, over the last, oh, eight or so years, to be amused by imbecilic Texan authority figures whose chief character traits are a cartoonish understanding of violence and an utter absence of basic human empathy.

*

If Laredo weren’t so awful, it would be a shame that Timeless’s two DVD collections (which contain the entire first season) cram five hour-long episodes onto each disc, coating Universal’s serviceable if slightly drab video masters in a thick blanket of artifacts and edge enhancement. Tate, also from Timeless, looks a little better. But it was Infinity’s Man with a Camera package that really impressed me. The episodes are transferred from 16mm, but the prints – from the collection of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, also the source of Mister Peepers and hopefully more classic TV gems to come – are in excellent condition, and they have been rendered onto DVD with about as much detail as one could hope from that format.